For those of you who have been missing my prose lately, I apologize – it’s the curse of having too many options, as I find myself wanting to write about every topic under the sun and being unable to simply pick one and go for it.

“Write what you know” is a common aphorism, one that I typically don’t endorse in the modern context: many modern writers take it to mean write yourself into your work, which is ill-advised. But writing about my profession is more in line with what the phrase is supposed to mean.

With that out of the way…

Land surveying is a little-understood profession in the modern world. It’s not immediately obvious why this is the case – if you’ve ever flown cross-country in an airplane and seen the relentlessly squarish grid that the entire Midwest follows seemingly religiously, you’ve seen the results of my profession.

My best guess is that my profession gets little of the spotlight because there isn’t much in the way of public results from my work. If I get called on to locate an entire municipal sewer system – because they built it 50 years ago and didn’t properly record all of the alterations that have been made in the intervening period, so they literally don’t know where all of the sewer lines are – there isn’t a bridge or even a building at the end of the months of work that it would take. All that the client would have gotten 10 years ago is a few big sheets of paper, and maybe some GPS coordinates. Nowadays they might not even get paper – they might get a CAD drawing file and a PDF with the signing suveyor’s digital signature and seal attached.

For those of you who aren’t familiar with land surveying, think of it as “high-resolution mapmaking” – with the typical intent of the map being to show land ownership or physical structures on it, and their spatial relationship to that land’s boundary. If you’ve ever bought or sold a house, there was probably an ALTA (American Land Title Association) survey involved (the bank will have insisted on one), which would (hopefully) show any legal encumbrances or easements on the property. You’ve probably seen us around – on the construction site, along major highways, in your neighborhoods. Likely you’ve mistaken our Total Station instruments for large camera (lots of people do).

While there are plenty of jokes about the ‘second oldest’ profession, in truth surveying is a pretty good candidate for it – certainly we’re the oldest one requiring a professional license. Even as far back as the Babylonian Empire, you couldn’t just grab some measuring tools and call yourself a surveyor; property ownership has been regulated by one legal authority or another since at least the advent of agriculture, and deciding whose fence is how far over whose property line stopped being academic and became a problem to fight over once small-time farming became commonplace.

The tools have certainly changed over the centuries. In ancient Egypt we were called “rope-stretchers” because the rope was the tool most commonly used for measurement and layout (surveying was a big deal in Egypt because the very land most useful for farming was also prone to regular flooding, which tended to wipe out many indicators of land boundaries). We don’t use rods (literally a wooden pole, measuring 16.5 feet) or Gunter’s chains (literally a metal chain, with stakes attached, 66 feet long, divided into 100 links) anymore.

And we don’t lead our children to each corner of our property and have them beat their hands on it in order to ensure they remember where it is anymore, either (though the “beating of the bounds” is still done in some rural areas in Wales).

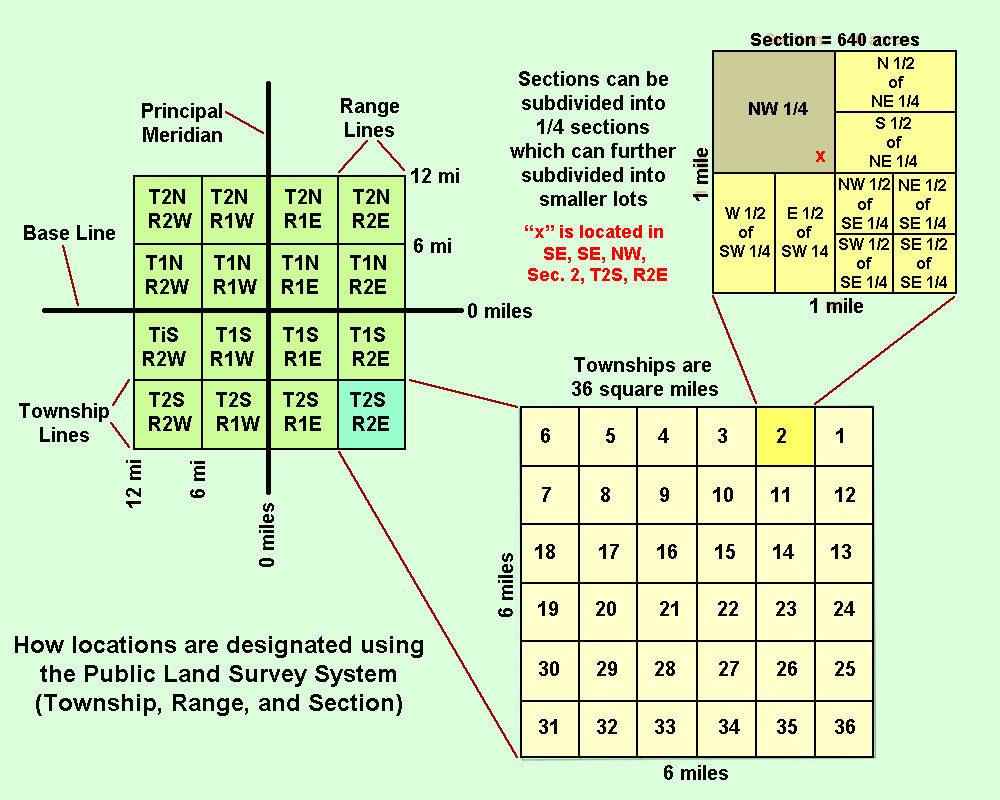

But few other professions have the kind of long-term effects that mine has had. I mentioned the square grid that much of America’s landmass follows – we can thank the Public Land Survey System created in the Land Ordinance of 1785 (yes, literally a pre-Constitutional system) for that. The newly formed Confederate States of America was land-rich but cash-broke and facing significant war debts, and the normal system of apportioning land for sale was too complicated and costly to carry out in anything like the time frame they needed to stay current with their debts.

The simple answer, then, was to lay out a square grid of 6-mile by 6-mile townships, divided up each into 36 1-mile by 1-mile square sections, all across the country (yes, this really was the simple answer). Surveyors were paid to lay out all of these square section lines – 80 chains each – typically at a fee rate of 2-3 dollars per mile.

Given that this was an era before even widespread availability of rail travel, this was pretty time-consuming, and of course very dangerous: surveyor teams in this era typically went everywhere armed.

As you can imagine, the accuracy of these section layouts varied wildly, and there was plenty of fraud, but piece by piece the skeleton on which modern cities, highways, towns and subdivisions are laid out were placed.

Mine is a profession where the goal of each new generation isn’t to outdo the quality of work done by the previous generation – it’s to retrace their steps. The history of my profession is part of every job I do, every billable hour I work, in a way that simply isn’t true of most other professions. When I’m surveying the sewer network of an entire city – which I’ve actually done – I have to start with the boundary lines of the sections that the city lies in where they are, not where they would have been had the survey team working in the swamp in 1832 had modern instruments. Every road, highway, train line, canal or subdivision parcel in any part of the country covered by the PLSS was placed where it is based on where the original surveyors placed those section corners.

As with tree rings, you can even observe historical events in my work. Here in South Florida, for example, plats that predate the Great War look less like surveys and more like pencil sketches, reflecting how most of this part of the state was given over to orange groves and sugar plantations. Then from 1919 until 1927, there was a big rush of people to move here, so the drafting quality improves dramatically – measurements ceased being recorded in chains and links during this period – and then almost no new plats are recorded from 1930 until after WW2, for obvious reasons. The 1970s saw the advent of photocopying, the early examples of which haven’t survived the decades all that well, resulting in many plats that are almost illegible; this was also the era when surveying companies finally retired the last of their Gunter’s chains and began using steel and nylon measuring tapes exclusively.

The 1980s saw the earliest CAD programs becoming available, forever condemning the old drafting methods to the dustbin of history – my father owned a pen-plotter, and I was endlessly entertained as a child watching it draw his surveys. 1990s plats started to get GPS coordinates included for reference monuments and corners. The 2000s have been something of a renaissance for my profession with the advent of two new technologies: LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging – think RADAR but with a laser rangefinder) and GIS (Geographic Information Systems), and nowadays many road projects are done via LiDAR systems mounted to trucks.

And of course, there are plenty of historical luminaries who either were surveyors themselves or contributed significantly to it. My father – himself a surveyor – is proud of the fact that 3 of the 4 faces on Mount Rushmore were surveyors at one point in their lives (this is actually a common joke with my colleagues – “Three surveyors and the other guy”). And even Roosevelt still managed to make major contributions to the profession via the work he created for us (the Panama Canal being one example).

Some things in my profession haven’t changed much. I could take a Babylonian plumb-bob and use it as-is, or take a modern one back to 2000BC and give it to a local surveyor with no instruction: there’s simply been no way to improve on the original design.

Like farming, surveying as a profession changed very little, and slowly, until the early 1950s. But technology marches ever onward, and with the advent of optical plummets – which have been common on Total Stations for at least twenty years – there is less and less need for the plumb-bob anymore. Field notes written on paper are slowly but surely being replaced by their digital counterparts. Many original section maps survive only in digital form now. A lot of small survey firms still have dumpy levels from the turn of the 20th century in use – but digital levels are slowly replacing them. Ours is hardly alone among the professions in seeing complete seismic shifts in how our work is done – doctors are facing down a future where diagnoses are done by AI, faster and more accurately than any human ever could – but the focus on history isn’t likely to ever go away.

The men who came before me are in every line I draw, every measurement I take. And when I finally get my own seal, they’ll be in every survey I stamp, too.