USS Indianapolis (CA-35)

In the aftermath of the First World War a series of armament agreements sought to restrict tonnage limits of capital ships. These tonnage limits also controlled the number of capital ships the signatory nations were allowed. Five nations signed the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 intended to forestall a naval arms race. The five signatory nations were: the United Kingdom; the United States; Japan; France and Italy. A series of coup attempts inside the Japanese government would lead to Japan rescinding its cooperation with the treaties in 1936.

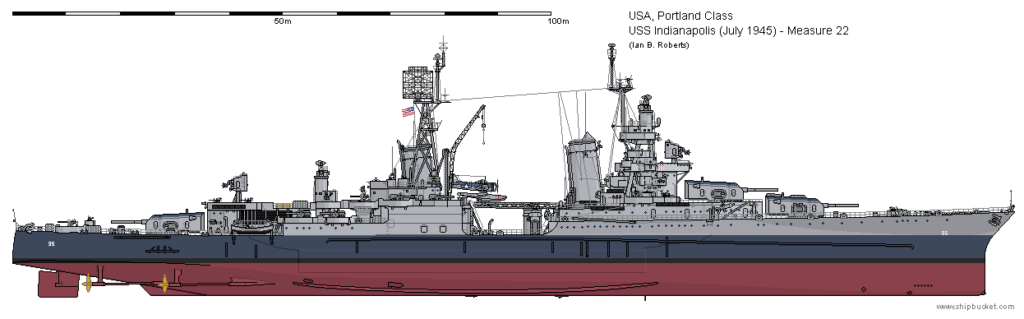

Congress approved the building of the Portland class vessel and ordered the “Indianapolis” be built February 13, 1929. The contract was awarded August 15, 1929 to the New York Shipbuilding Corporation located across the Hudson River from New York City at Camden, New Jersey. Portland Class Cruisers were designated as Fleet Flag vessels and subsequently were built to accommodate an Admiral and his staff. Her keel was laid down March 31st, 1930, launched November 7th, 1931 and commissioned November 15, 1932 after a shake-down cruise that took her to Europe and the Caribbean.

Originally classified as a light cruiser (CL-35) due to her light armor but reclassified as a heavy cruiser (CA-35) due to her 8 inch guns July 11, 1930 under the auspices of the London Naval Treaty of 1930. The 1930 treaty also addressed submarine warfare and reclassification of cruisers not due to armor cladding or weight limits but rather to the size of gun bore. Light cruisers were outfitted with 6 inch guns while heavy cruisers carried 8 inch guns.

Making her debut as the “Ship of State”, she was to be President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s transportation from CampoBello Island in 1933, a naval review during 1934 and a goodwill tour that took him to a number of state visits in South America in 1936.

President Roosevelt was to board for a South American goodwill cruise embarking at Charleston, South Carolina November 18, 1936. The Indianapolis would make ports of call simultaneously with -visits of state at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Buenos Aires, Argentina and Montevideo, Uruguay and then returning to Charleston and disembarking the President on December 15, 1936. Designated the flagship of Scouting Force 1 on the First of November 1933 and retained that designation until late in 1941.

As the attack on Pearl Harbor was underway, the Indianapolis was conducting naval exercises at Johnston Atoll south of the Hawaiian Islands. The “Indy” was about to become a fighting ship.

Making her debut as a ‘fighting ship’, attached to Task Force 12, she and other vessels searched for the Japanese force that had conducted the raid on Pearl Harbor. Unsuccessful in her search, she returned to Pearl Harbor 13 December 1941 and joined Task Force 11.

The USS Indianapolis would be a heavy participant in the Second World War…

Task Force 11 steamed into the South Pacific escorting the carrier USS Lexington and was involved in the Battle of the Coral Sea. Considered by many to be a draw, the 4 day battle that raged from May 4 to May 8, 1942 would see both sides lose aircraft, ships and men. Both sides would see a carrier sank, for the US, ( USS Lexington) and a carrier damaged (USS Yorktown); for the Japanese (the light carrier Shoho sank) and ( the carrier Shokaku damaged); plus a number of support vessels of both navies either sank or damaged in the first major US naval offensive of the Second World War.

August 7 her guns were to rattle the Japanese on Kiska Island, Alaska setting the stage for a repulse of Japanese forces from the Aleutian Islands. In a fog shrouded engagement the Indy’s guns would destroy ships, planes and gun emplacements in the first action against the Japanese invasion of islands in the Aleutian chain.

January 1943 opened with the Indianapolis supporting landings on Amchitka Island as part of an American island hopping strategy to push the Japanese off the Aleutian Chain. Her duties would keep her in Alaskan waters till mid-year.

After a refit at Mare Island Navy Yard she was ordered to Hawaii as the flagship for Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commander of the 5th Fleet. As flagship for Operation Galvanic, her guns would see duty at Tarawa and Makin through November of 1943.

As the 5th Fleet’s flagship, in January and February 1944, her guns would pound islands in the Kwajalein Atoll. In March and April she would see duty in the Western Carolines. June 11 to June 13 would bring her to the Mariana Island group and the Battle of Saipan. June 19 she participated in the Marianas Turkey Shoot. June 23rd she would be back to Saipan; on the 29th she would begin operations in the Battle of Tinian.

She would operate in the Mariana’s group for several weeks before returning to the Western Carolines to join the Battle of Peleliu in September. A tour of duty in the Admiralty Islands and a return to Mare Island Naval shipyard for refitting would round out her activities for the year.

A newly overhauled Indianapolis would return to active duty as part of Admiral Marc Mitscsher’s fast carrier group on February 14, 1945. This force was to attack Tokyo February 16, the first carrier attack on Japan since the Doolittle Raid in April of 1942. Two days of raids produced a 10:1 kill ratio for US Naval aviators (49)aircraft lost v/s Japanese air forces(499) aircraft destroyed in addition to sinking a number of Japanese naval vessels and severely damaging shore installations.

Planning for the Okinawa campaign assigned the fast carrier task force to suppressing Japanese air forces from mainland Japan in advance of the invasion of Okinawa. In an air battle on the 21st of March, 24 American fighters from the task force intercepted and shot down all 48 Japanese aircraft sent to destroy the task force.

Returning to Okinawa on March 24, the Indianapolis pounded the landing beaches and defensive positions with 8 inch shells all the while being attacked by Japanese aircraft. On March 31, the Indy’s surprisingly long run of minor battle damage came to a halt as a bomb penetrated entirely through the ship, only to explode beneath the vessel. Nine crewmen lost their lives, either due to the concussion that ripped her hull or the subsequent flooding. Emergency repairs and inspections revealed serious damage to the ships propulsion system, ruptured fuel tanks and damaged water distillation equipment prompting the Navy to send the vessel on the long journey to the Mare Island Navy Yard for repairs. The proud Indy returned to the west coast under her own power.

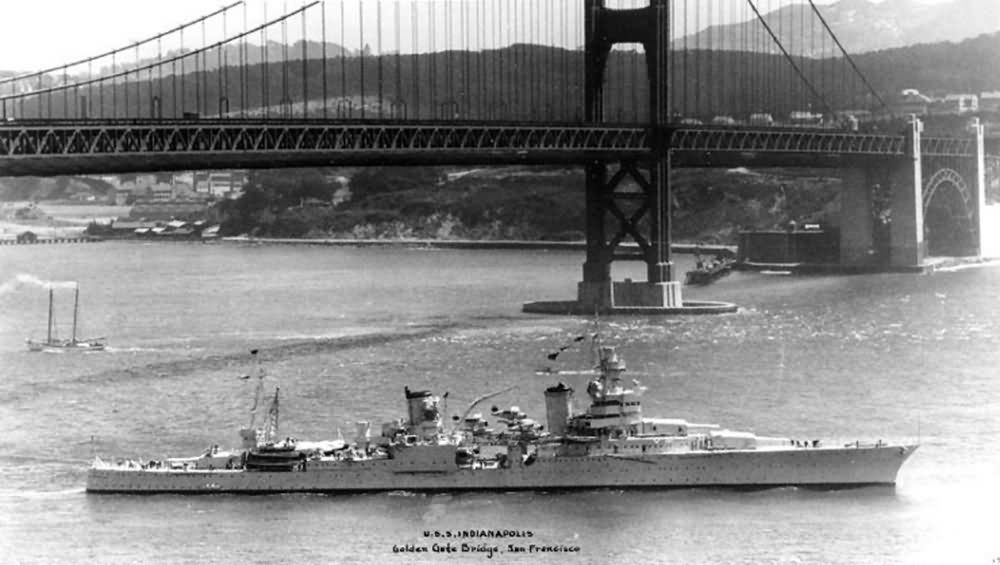

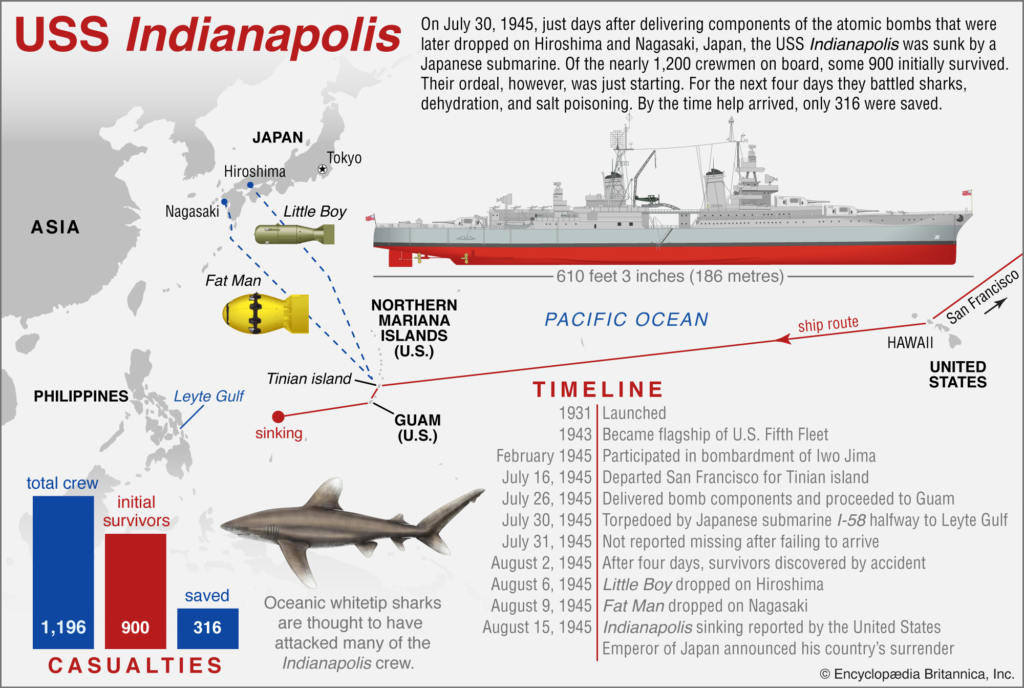

With repairs completed, the Indianapolis departed San Francisco July 16, 1945 shrouded in secrecy for the Island of Tinian arriving July 26, with vital parts for the atom bomb that would be dropped on Hiroshima. Departing Tinian with a stop-over at Guam to make crew changes due to rotation; leaving Guam on the 28th, she began the journey toward Leyte.

At fourteen minutes after midnight, July 30, 1945 the Indianapolis was struck by two torpedoes fired from a Japanese submarine to her starboard bow resulting in severe damage. She began to list and settle by the bow. Three stations received the distress calls of the Indianapolis but none responded or reported the distress calls. Twelve minutes later, the Indy went down, trapping approximately 300 sailors aboard.

“I swam as fast as I could to get away from the ship because I was afraid of the suction taking me down as the ship sank. The first thing that was so horrible was the fuel oil that covered the water. Every breath I took made me so sick I vomited everything I had in my stomach.” Maurice Bell, USS Indianapolis Survivor

Indianapolis native and USS Indianapolis survivor, James O’Donnell “When I looked back… all you could see is the back end of the ship going straight down”.

Nearly 900 men went into the water, 321 men were rescued, of that number 317 survived. For three and a half days the crew of the Indy would die due to dehydration, salt water poisoning and shark attack.

“You had to stay in a group. If you didn’t stay in a group the sharks had you”. James O’Donnell

Due to procedural blunders and naval red tape, the loss of the Indy and the fate of her crew went unnoticed until discovered August 2nd, by a lone Ventura patrol plane piloted by Lt. Wilbur Gwinn, spotted the men adrift. A PBY Catalina under the command of Lt. Adrian Marks in contradiction of standing orders landed the plane on the sea and began plucking survivors from the water. He would so badly damage the craft as his crew tied men to the plane’s wings the plane could no longer fly and had to be sunk. Lt. Marks and his crew rescued 56 men that day. Rescue operations and the search for survivors would continue until the eighth of August.

James O’Donnell’s home town would not learn much of the disaster until the morning of August 15, 1945 when the Indianapolis Star would begin to tell the story of the Indy’s sinking via delayed (AP) press releases.

In November 1945, Captain Charles McVay III, Commander of the Indianapolis, was convicted in a controversial and contentious court-martial of; “hazarding his ship by failing to zigzag”. His sentence remitted by Admiral Chester Nimitz, McVay returned to duty, retiring as a rear admiral in 1949.

Driven by a stained military career and misplaced guilt for the sinking, Rear Admiral Charles McVay committed suicide in 1968 at age 70.

If not for the valiant efforts of a dedicated young Hunter Scott, the conviction of Captain McVay might never have been corrected. The plucky sixth grader would start a conversation that would eventually drive a congressional resolution of exoneration and be cleared of all wrongdoing by the Secretary of the Navy in July 2001.

In 2013, 28 year old Navy helicopter pilot Hunter Scott would say of the survivors, “They’re like grandfathers to me, it’s like seeing family. They’re heroes”.

Addendum: My effort here has been to highlight the USS Indianapolis’s extraordinary war record in the Second World War rather than dwell on her sad end.

Editor’s note: On August 19, 2017, a search team financed by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen located the wreckage of the sunken cruiser in the Philippine Sea lying at a depth of approximately 18,000 ft. In September 2017, a map detailing the wreckage was released. The main part of the wreck lies in an enormous impact crater; her bow, which broke off before the ship sank, lies 1.5 miles east. The two forward 8-inch guns, which also broke off on the surface and mark the ship’s last position on the surface, lie 0.5 miles east of the main wreck. The bridge, which broke off the ship due to the torpedoes, lies in a debris field near the forward guns. The single 8-inch gun turret on the stern remains in place, though the stern’s roof collapsed over itself. Airplane wreckage from the ship lies about 0.6 miles north of the main part of the wreck.