SS Edmund Fitzgerald, laid down in 1957, was the largest ore ship on the Great lakes. She was 729 feet in length, had a beam of 77 feet and drew 25 feet at full displacement. She was capable of carrying 26,500 tons of bulk cargo in her 3 cargo holds. On 10 November 1975 the Edmund Fitzgerald went to the bottom together with her crew of 29.

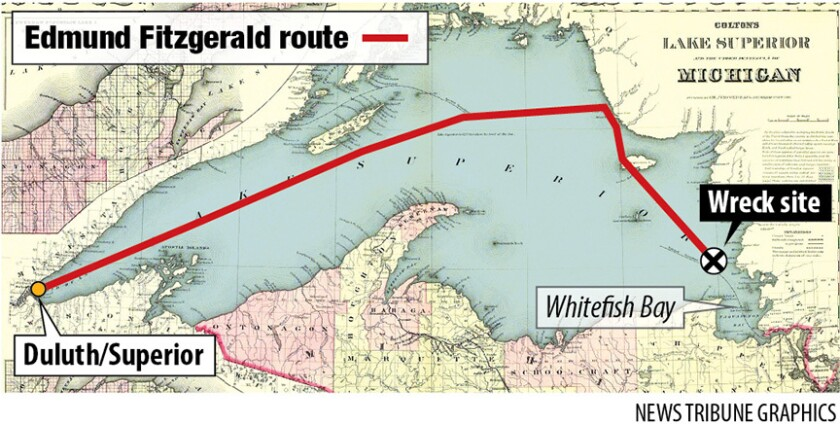

The final, fateful voyage started at the wharves of Superior, Wisconsin where she loaded 26,116 tons of taconite ore pellets. The ship departed Superior at 1415 on 9 November bound for the steel mills at Zug island, close to Detroit. The NWS forecast at the time of departure was nothing of concern for the giant freighter or her captain, Ernest McSorely.

He assumed command of the Edmund Fitzgerald at the start of the 1972 shipping season and had commanded nine ships before joining the Fitzgerald crew. A quiet man, McSorley was well respected by his contemporaries as a skillful master and by his men, whom he treated as professionals. He turned 63 a month and a half before the Fitzgerald incident, and intended to retire at the end of the shipping season. He was respected throughout his career as a superb heavy-weather captain.

The weather, initially forecast to be moderate, took an ominous turn. At 1900 on the 9th the NWS issued a gale warning, and Fitzgerald altered her course northward. At 0200 10 November, the NWS upgraded the forecast to a storm. Land stations and the Arthur M Anderson recorded winds in excess of 50kts. The Anderson was travelling in company with the Fitzgerald. Fitzgerald herself reported 10 foot waves.

Around 1530 on the 10th, McSorely reported his ship was taking on water and had developed a list after losing two vent covers to Jessie Cooper, the captain of the Anderson. At 1610, McSorely reported a radar failure and asked if the Anderson could keep an eye on his ship. Fitzgerald slowed to let the other vessel close the distance between the two.

The weather continued to worsen. Anderson logged winds at 58 knots at 4:52 p.m., while waves increased to as high as 25 feet by 6:00 p.m. Arthur M. Anderson was also struck by 70 to 75 knot gusts and rogue waves as high as 35 feet.

At approximately 7:10 p.m., when Arthur M. Anderson notified Edmund Fitzgerald of an upbound ship and asked how she was doing, McSorley reported, “We are holding our own.” She was never heard from again. No distress signal was received, and ten minutes later, the Anderson lost the ability either to reach Edmund Fitzgerald by radio or to detect her on radar

Captain Cooper attempted to notify the USCG of his concerns about the Fitzgerald, but the duty officer, Petty Officer Philip Branch, later testified, “I considered it serious, but at the time it was not urgent.” The response, already delayed by the Coast Guard, was further delayed by the weather. The initial search was carried out by the Anderson and another laker, the William Clay Ford. The Coast Guard sent a buoy tender, a HU-16 flying boat and a HH-52 helicopter to aid in the search. Other than some debris, nothing was found.

On her final voyage, Edmund Fitzgerald‘s crew of 29 consisted of the captain; the first, second, and third mates; five engineers; three oilers; a cook; a wiper; two maintenance men; three watchmen; three deckhands; three wheelsmen; two porters; a cadet; and a steward. Most of the crew were from Ohio and Wisconsin; their ages ranged from 20 (watchman Karl A. Peckol) to 63 (Captain McSorley)