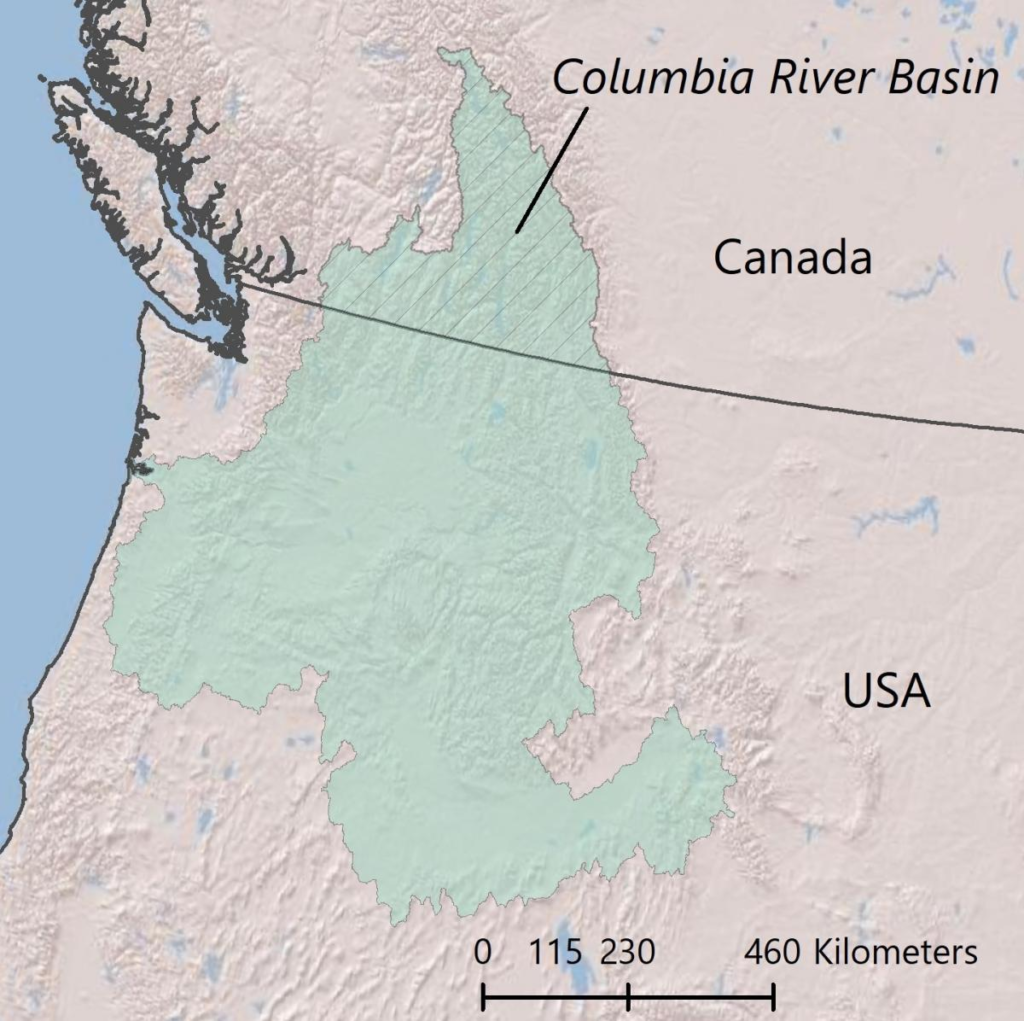

The Columbia River begins its 1200 mile journey to the Pacific Ocean from its headwaters in the Canadian Rockies. This ancient river predates the lava flows that covered the North West with lava 2000 feet thick or more some 15 million years ago. The river was already old when the Cascade Range came into being 5 to 6 million years ago. The river and its course were well determined by the time of the Spokane Floods at the end of the last Ice Age.

It was these catastrophic floods that gouged out and created from the hard basalt the falls and rapids resulting in numerous swift flowing river channels. This fifteen mile stretch of the Columbia River would later be called The Dalles, a French word meaning gutters. Starting with Celilo Falls at the upper end of the river’s descent and ending at the present day town of The Dalles, Oregon, this run of river was the focal point of a fishery that flourished for 10,000 years.

A barter economy evolved because this series of natural falls and rapids allowed an inventive people to harvest the runs of salmon and steelhead trout. Trade items from the Great Lakes, the Great Plains and the Desert Southwest were circulated and traded but it was the dried fish that dominated this barter economy.

In a system that evolved in pre-Columbian America the Indians netted or speared then dried the fish. After drying, the fish was pounded into a meal then packed in special made tightly woven baskets. By following a carefully orchestrated process, spoilage was minimal allowing the fish to be transported and stored for multi-year periods.

The journals of Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark noted that taking fish and drying the catch was prevalent on all the rivers and streams that supported fish runs. It was only at Wy-am, the Indian name for the series of falls and rapids, that the practice was turned into an industry large enough to attract trade on a sustainable scale. The Corps of Discovery commanders would call Wy-am the greatest market of its kind west of the Rocky Mountains.

Fishing was tightly monitored, bound by ritual and tradition that honored the salmon and the prodigious bounty the river provided. The fishing season could only be started by an elder designated as the Salmon Chief. Fishing commenced and ended for the day by a shrill whistle. Favored sites were handed down within one’s family or clan and jealously guarded.

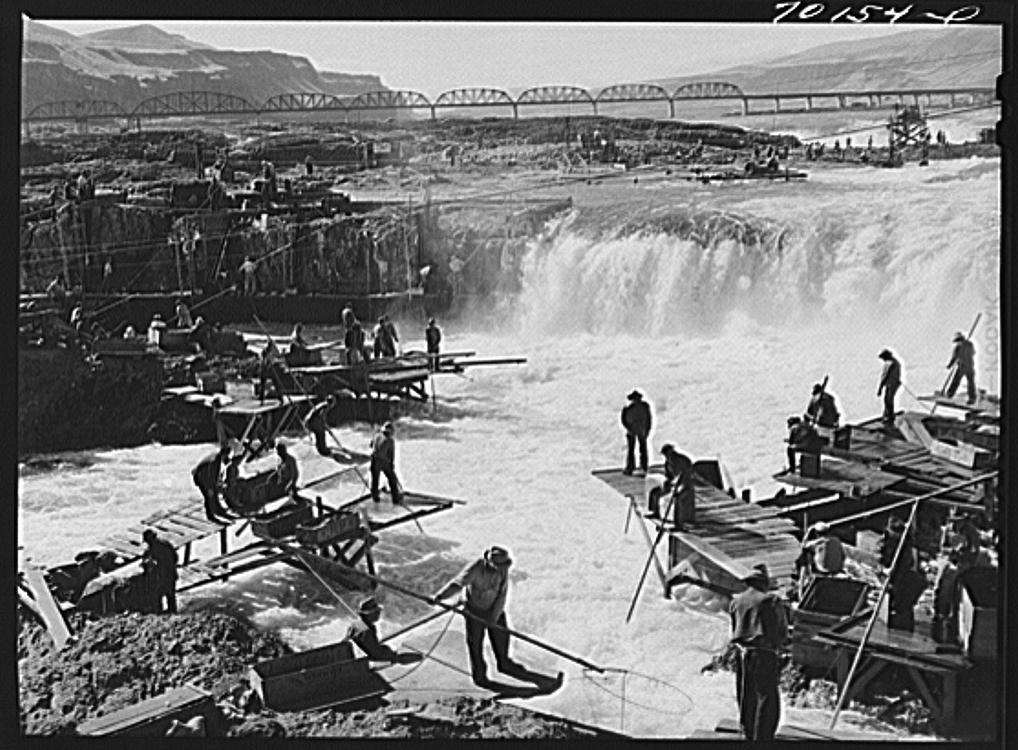

Russell Lee/Farm Security Administration

Fishing was conducted from platforms built out over this cauldron of mist, foam and water using dip nets and spears. The combination of fish blood, slime and the ever present mists from the roaring water made working from the platforms dangerous. It was considered a rite of passage for a young man to begin to work from the platforms. A fall into the water was generally fatal. For this reason when a life was lost, fishing was suspended for the day.

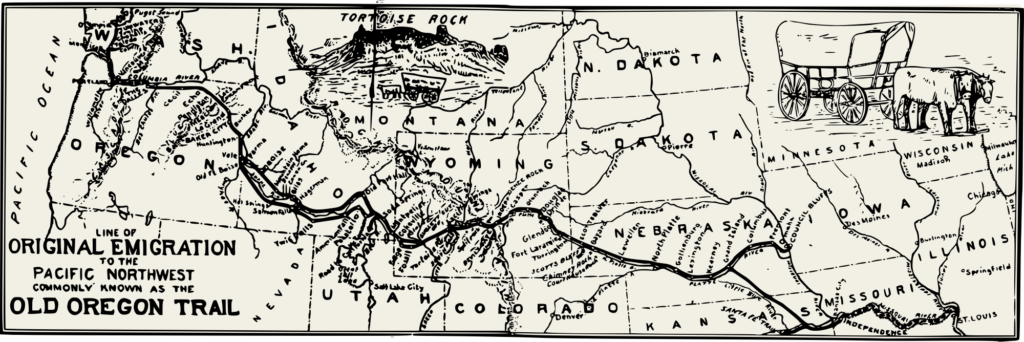

Throughout the 1840s people streamed west seeking opportunity. At The Dalles the wagon trains opted to continue down the Columbia via ferry to the Willamette Valley, or take the more arduous but cheaper Barlow Road over the shoulder of Mt. Hood to the Valley of the Willamette. The Dalles being a major stop over for the Oregon Trail enticed some to settle in the area.

As the newcomers sought land, bought fishing rights and created a new life for themselves, they came into conflict with the Indians. From a few isolated incidents, the conflict escalated to the Whitman Massacre on the evening of November 29, 1847.

The resulting “Cayuse Indian War” would ultimately involve a number of other tribes in the conflict that dragged on sporadically for eleven years. Washington Territorial Governor Isaac I. Stevens traveled to the Walla Walla Valley and concluded a series of treaties signed June 9th, 1855. Conclusion of the treaties would ultimately create four Indian Reservations, the Nez Perce, the Umatilla, the Warm Springs and the Yakama and guarantee the Indian Rights to fish the Columbia with Senate ratification in 1859.

“The exclusive right of taking fish in the streams running through and bordering said reservation is hereby secured to said Indians, and at all other usual and accustomed stations in common with citizens of the United States”. As whites had purchased numerous fishing rights from the Indians up and down the Columbia, the language “in common with citizens of the US”, was considered necessary to protect their property rights as well.

At the time of the Walla Walla treaties of 1855, no one could imagine the mighty Columbia being controlled in any way. In an undated letter thought to be written in late 1840, Henry Spaulding, an early missionary in the Oregon Territory wrote: “The Salmon will be arrested in their upward course by some measure which the untiring invention of man will find out…” His words were more prophetic than he could know.

The fishery at Wy-am continued although its dominance began to wane as more and more fish were taken in the Lower Columbia. By the 1870s the proliferation of canneries and commercial fishing would drive down the price of salmon. The more serious issue was commercial fishing and cannery industries were beginning to make serious inroads to the salmon returning up river. The Indian protests of waste, fish left to rot were ignored, causing outbreaks of random violence up and down the river, keeping the Army and the courts busy.

NOTE: One fish wheel near The Dalles pulled 418,000 pounds of fish from the river in the 1906 season alone. It was but one of some 75 fish wheels in operation on the river that year. A burgeoning gill net fleet would also contend for fish. Fish wheel operators and gill netters were to blame each other for the decline in fish numbers for years. Fish wheels were finally banned in 1935 and gill net seasons were severely restricted but the salmon continued to decline.

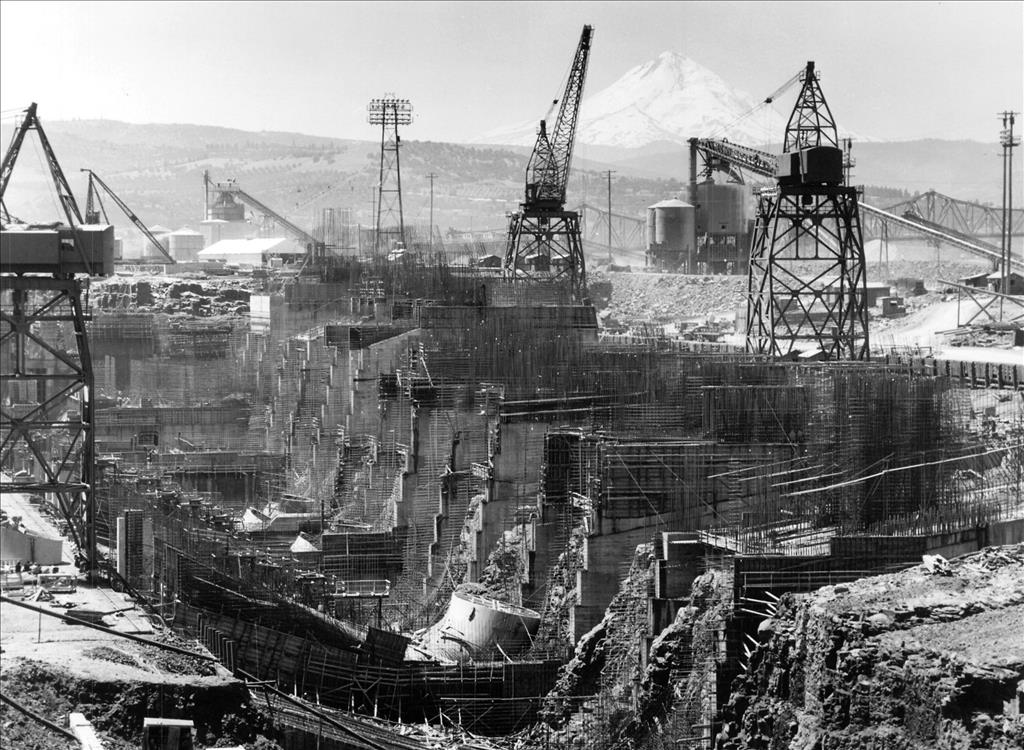

The early twentieth century brought the demand for cheap electric power, it was decided hydro-electric power could satisfy the demand and help the northwest to grow. The construction of two dams began, July 16, 1933 at Grand Coulee followed in 1934 with the start of Bonneville Dam. Bonneville began power production in 1937 its innovative fish ladders helped the fish continue to migrate up-stream.

Grand Coulee on the other hand was too high for the use of fish ladders thereby baring the migrating salmon. The Native American fishery at Kettle Falls was inundated in June 1940 along with 120,000 acres of land in the waters of Lake Franklin D. Roosevelt. The loss of thousands of miles of traditional salmon spawning grounds was to be balanced by an enlarged and enhanced hatchery system in the Lower Columbia that never came to fruition. After years of wrangling in the courts, the government finally settled with the Colville Tribe for $53 million in 1994 with annual payments of $15.25 million beginning in 1996.

As the United States began to gear up for the coming Second World War, demand for electrical power soared. By 1942 Columbia River hydro stations were supplying approximately 95% of all electrical power for the Pacific North West’s war industries. Shipbuilding, the aircraft industry, aluminum production and the super secret Manhattan Project, all used mega amounts of electrical power.

War planners fearing the war in the Pacific might continue into 1947 and anticipating further demands for electrical power began to survey other sites. The Army Corps of Engineers selected the present site where a mountain of basalt shoulders towards the river. The proposed dam and the pool behind it would inundate the ancient fishing sites.

As soon as the site was announced the Tribes began to question the government’s commitment to the Treaty of 1855. Congressional hearings in 1947 decided that the Tribes right to fish the river would not be violated; even though flood waters would cover the falls and rapids.

March 10, 1957 the gates of The Dalles Dam closed, eight hours later, the falls at Celilo went silent and 10,000 years of tradition would be no more. The government settled with the Tribes for a paltry $26.8 million for the loss of the fishery at Celilo and other sites.

Yes, Indians still fish the waters of the where once roared the falls. Instead of platforms and dip nets, gill nets and motor boats dominate the scene of a dusty village on a shoulder above what was once the greatest market west of the Rockies.

NOTE: The average daily discharge from The Dalles Dam since the dam’s completion has averaged 138,000 cubic feet of water per second; converted to gallons that’s: “One Million, Thirty Two Thousand, Two Hundred Forty” gallons per second. Pre the dams, flood stage over the falls has been estimated to be in excess of 1 million cubic ft per second.