Much is made in modern history about our Nation’s westward movement. While important, the first to venture into this continent were the Native residents the European powers encountered. Columbus, by his “Discovery” triggered a flood of exploration to the New World, which in turn ignited a land rush, lands to be claimed in the name of their sovereign.

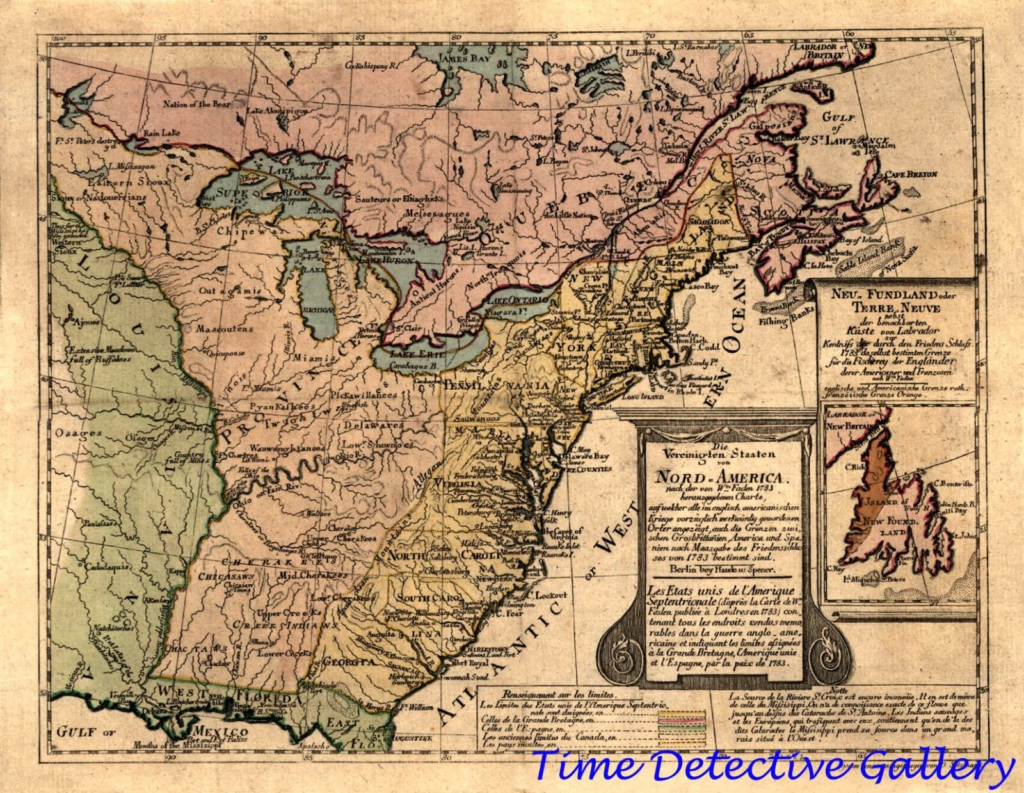

In North America the contenders were Spain, France, England and Holland. The first to stake claims were of course the Spaniards; with claims extending into present day Florida with Ponce De Leon’s landing in 1513. Jacques Cartier made claims for France in 1534. Two private enterprises, one at Jamestown (1607), a commercial venture; and one at Plymouth (1620), a religious community; established the English claim. The Dutch arrived in 1624, only to be ousted by English war ships some 40 years later.

No one survived the failed Roanoke Island settlement, an enduring mystery, but stubborn men prevailed and Jamestown was the first successful settlement with its own tale of horror. Nevertheless, permanent settlement had begun by people whose progeny would become the founders of this Nation. Started as a commercial enterprise, the Colony of Virginia needed farmers and craftsmen. Convicts, many from the debtor prisons, a few free blacks and indentured persons, both men and women made up the major part of the new immigrants. A few landowners came to oversee operations as the colony began to grow and prosper. As the indentured fulfilled their contracts, many chose to move westward where land was there for the taking.

NOTE: Lawrence Washington, grandfather of future president George Washington migrated to Virginia in 1657.

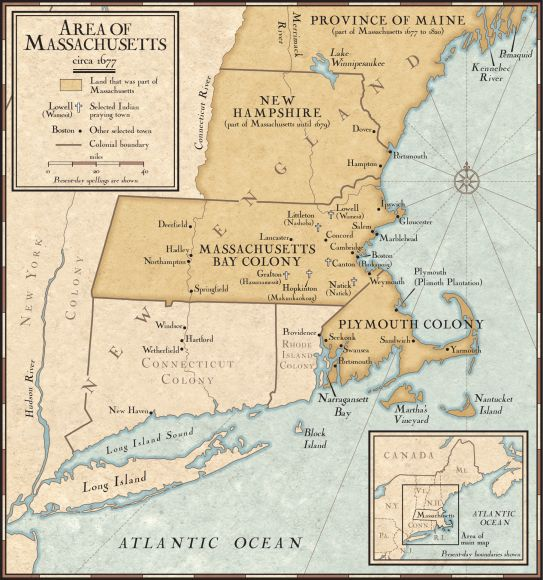

On the rocky coast of New England the settlers were seeking refuge to practice religion on their terms. Community farming helped the early groups to survive the harsh New England winters. As the colonies grew the family farm became the mode, necessitated even more by the rocky New England soils, thus further expanding the settlement of the land. As others of differing views came, they settled apart, thereby spreading the population, north, south and ever westward.

Between 1626 and 1638 six additional colonies were chartered, New York, Maryland, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Delaware, and New Hampshire. Maryland was chartered as a refuge for Catholics. From 1653-1682 four more colonies were organized namely North Carolina, South Carolina, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The late comer and the last of the 13 original colonies in 1732 was Georgia. Convicts, indentured servants and slaves continued to bolster the population. A burgeoning population and the thirst for land drove the ever expanding settlement further and further from the sea board, westward, ever westward.

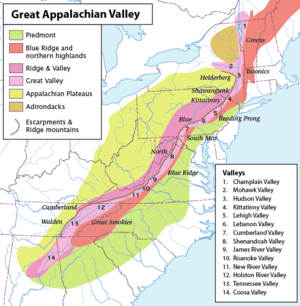

The vast reaches of Chesapeake Bay and its network of sub-bays and navigable river inlets opened a large area to settlement. As the first settlers claimed lands near navigable rivers and creeks, more settlement was pushed into the upper lands of the Atlantic Coastal Plain. Reaching the fall line, that 900 mile escarpment that runs from New Jersey to Georgia, settlement entered the rolling hills of the Piedmont. This expanse of land was soon to see settlers leave for lands nearer the Blue Ridge, the more intrepid venturing into lands west of the vast Appalachian Chain, many via the Cumberland Gap; again westward, ever westward.

This pattern of westward movement was to be repeated throughout the colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia with hearty souls looking to settle land they could call their own. This thirst for land was driven by the poverty of the common people and the lack of European land available for private title. The lure of land that belonged to those with the courage to take it was a powerful incentive. A British ban on settlement of Indian land did little to stop the spread of settlement and the westward march continued. The French and Indian War momentarily slowed the flow westward but resumed its relentless march after the Revolutionary period almost unabated.

The French and Indian War as it was known in Colonial America pitted Colonial Americans and British Regulars against French Regulars and their Indian allies. The brutality and savagery of the war stymied the westward movement but resumed with even greater push once hostilities ceased. The American Revolution also would have a dampening effect on the flood of settlers.

As the land filled up along the creeks and rivers, the migrants were forced into lands further and further from the coastal areas. The desire for land was so great the populace began to look at the “Blue Ridge”. That far ridge was but a “Blue Bruise” on the horizon; the barrier to expansion that as time went by could no longer hold back the flood of settlers.

There were 5 main ways or routes to gain access to lands west of the Appalachian chain; the 3 overland routes that crossed these mountains, the Erie Canal after its opening and entering from ports on the Gulf Coast held by hostile foreign powers. Even to get to these departure areas was a journey all its own. We often forget that the east coast of North America was a wilderness. Few roads and the ones that did exist were often little more than trails suitable to foot traffic and horseback only. It is small wonder the majority of travel within the colonies was by mail packet or ship.

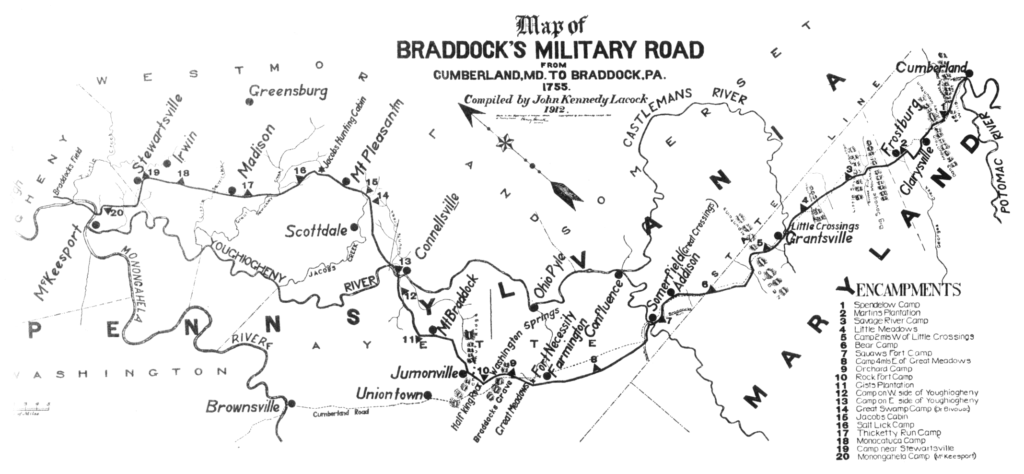

The first real obstacle to the westerly migration was that imposed by the Appalachian Mountains. Of the many passes, notches and gaps that exist within the Appalachian Chain, many led to blind ends or passes that were so steep and or narrow that passage was not possible. Of this myriad of passes, three would see the majority of the westward migration. Two were well known and in use by 1750, Nemacolin’s Path in western Maryland and The Kittanning Path in south/central Pennsylvania.

The Kittanny (Kittanning) path located in western Pennsylvania as the northernmost of the three routes, accessed the Ohio country from the upper reaches of the Susquehanna River system through the Allegheny Gaps near present day Altoona, Pa. Much of this route today is US #22, an east-west national highway.

Nemacolin’s Path in northwest Maryland, the middle route presented another viable crossing of the Appalachian crest to the Forks of the Ohio. A route favored by a young George Washington that started at the upper Potomac and led to Fort Duquesne located near the Forks of the Ohio. British General Edward Braddock was killed and his command nearly wiped out except for the valiant efforts of a young Col. Geo. Washington on this path. The eastern section of Nemacolin’s Path would later be called Braddock’s Road and later still become part of the US Highway System as US #40.

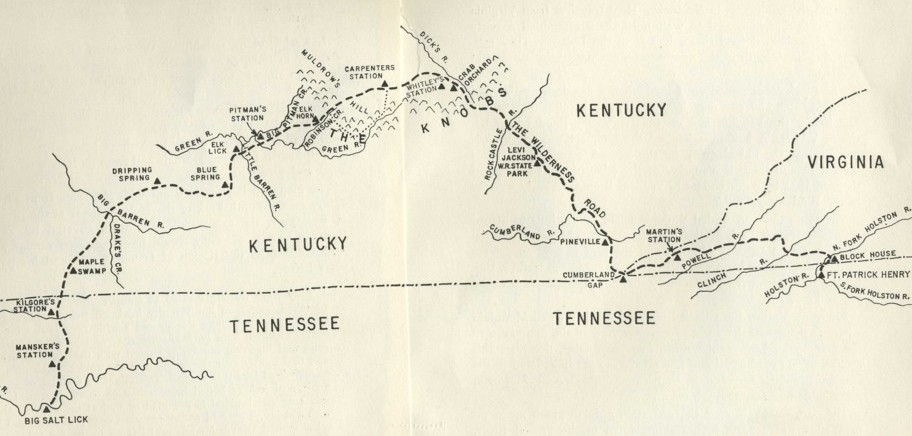

Of the three trails into the wilderness the final and most well known is the Cumberland Gap. It’s very possible the first European to traverse the Gap was Gabriel Author in 1674 as an Indian captive. The Gap would become the focal point of the “Loyal Land Company” in 1750 under Dr. Thomas Walker. North Carolina judge Richard Henderson hired frontiersman Daniel Boone to blaze a trail through the Gap into central Kentucky. Boone’s reputation as an Indian Fighter and survivor of the Braddock disaster helped many to make the decision to join the migration into new lands. Improvements to the trail converted what had been a narrow track into an all weather road by the turn of the century called “The Wilderness Road”. It would cease to be a major route by 1840 and no major east/west highways access the Cumberland Gap to this day. A National Historic Park preserves what remains of the wilderness that this area once was.

The year is 1750 the population of Colonial America is approximated to be 1.3 million people. Benjamin Franklin wrote, “Our people must at least be doubled over 20 years.” It is no wonder the restive population saw western expansion as both logical and necessary. Dr. Franklin’s observation would prove to be very prophetic.

Thomas Jefferson’s father was involved in the “Loyal Land Company” with Dr. Walker. As early as 1750 prior to the start of the French and Indian War the founders of the Loyal Land Company had offered up suggestions of exploration up the Missouri River all the way to the Pacific. The 7 Years War, as it was known in Europe, would intervene and further exploration would wait for the mountain men. Many of these intrepid individuals were more a social outcast from society but it was they who would find the trails and routes that would bring more settlers.

The years after the Revolution allowed the fledgling United States to invent itself as the 13 Crown Colonies became the United States of America, an appellation that stands to this day. Over a three year period the Colonies were individually accepted into the new United States by 1790. The new nation would add three additional states by 1800 with the addition of Vermont, Kentucky and Tennessee as they ratified the US Constitution.

As the new century arrived the country was like a tight wound spring as the early years of the 1800s exploded with several new states and widespread exploration to the west. It was this western exploration that would have such a profound effect on the history of the American West. Another chapter in America’s tumultuous destiny was about to unfold.

Ed. note: The next chapter will be published next Monday.