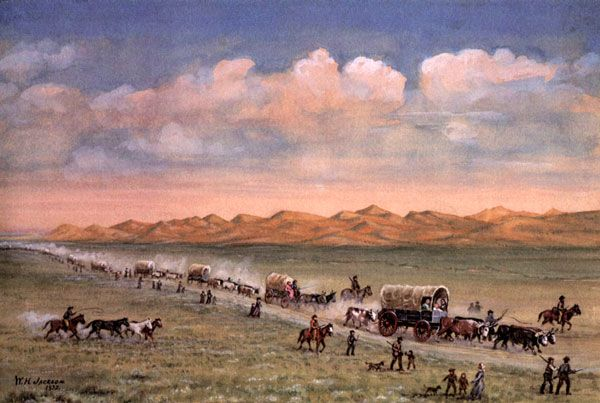

The grass is greening and prairie flowers are painting the land with colors. Warm breezes smelling of drying dirt, fills the air as the moisture from the winter snows begins to dissipate into the prairie soil. It is April 1843 and the trails west are not yet ready to allow the heavily laden wagons passage without bogging in the soft ground. The pack trains of horses and mules have left, leaving torn turf to mark the way west and leaving the wagon trains to wait for the prairies to firm up. It is a time of high anticipation in the trains, sending scouts to check the condition of the trail while families make last minute checks of supplies and goods.

Eureka!! The wagon master has called a meeting declaring we start tomorrow morning! The ground is sufficiently dry to carry the weight of the wagons; assignments are made, the lead wagon today will be the tail wagon tomorrow as the entire train will rotate through the daily lineup so no one wagon has to eat dust all the way to Oregon.

A stark warning from the wagon master, stragglers will be left behind as the train must be over the Blue Mountains before the first snow. He explains that wet snow fall makes for wet firewood and snow covered graze and no train can survive days without fire wood or graze for the animals. Heavy, wet snows can fall in early September and the storms can last for days. It is now late April, the countdown starts.

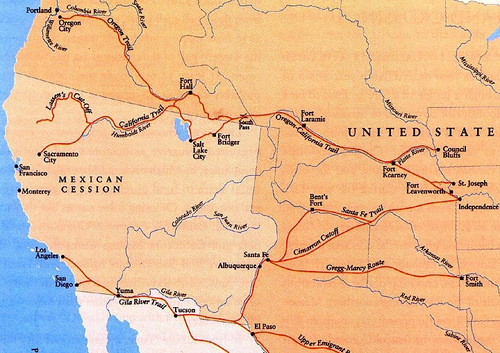

From Independence and St. Joseph in Missouri and Council Bluffs in Iowa territory the trains begin the long haul to a new home. They all begin in the wooded lowlands of the rivers and gradually see the trees give way to open prairies and wide open skies. The open country is a change from the closely wooded country east of the Mississippi, some become despondent as the country becomes less wooded and more open prairie while others find it exhilarating.

The trains were often slowed by the creeks and rivers as many were still swollen with snow melt and spring rains. The progress was often measured in landmarks rather than miles, miles suggested great distances while landmarks were so many days travel. When the trains passed the first of the many landmarks they would pass, it signified the journey had truly begun. It was the landmarks that the journals of the travelers wrote about as they crossed the continent. It was noted as they passed where the Santa Fe Trail split from the Oregon Trail and it was with some anticipation they drew up the train at the base of The Blue Mound. The Mound allowed a view “all the way to Oregon” or so it was laughingly claimed.

All the trails from the jump off points come together on the Platte River near Fort Kearny in central Nebraska. Trains out of Independence and St. Joseph travel the south side of the river while trains out of Council Bluffs travel the north shore. The Mormon eviction from Illinois forced families to leave with few belongings and little notice. This would be the start of the “hand cart battalions”. Utilizing the north shore of the river to the forks of the Platte the Mormon migration route would follow that of the Oregon Trail over the Continental Divide.

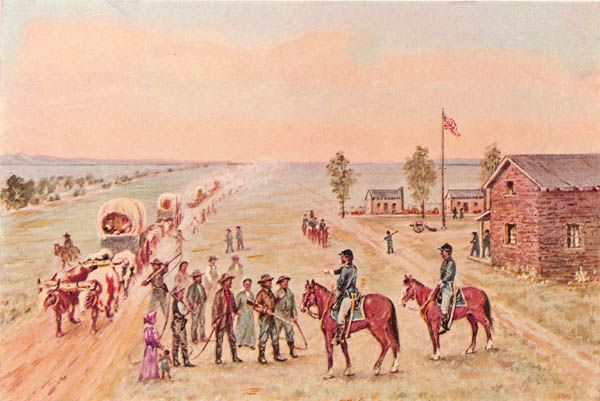

Erected in 1848 Fort Kearny located in central Nebraska was selected by the Army as the post that would guard the lower reaches of the Oregon Trail. Prior to that date all trains simply merged and continued west up the Platte. A settlement called Dobytown would spring up next to the fort and it would become a center of trade for the immigrants. The community and Fort Kearny would become a sanctuary for trains during the Indian Wars that lasted throughout the western migration years of 1854 to 1865.

Indians were not the only danger on the Great Platte River Road. A cholera epidemic claimed hundreds of lives during the years 1849-1855 as many of same the camp grounds were used repeatedly. The lack of sanitation and contaminated water decimated the travelers, as the causes and treatments for cholera were unknown at that time.

To avoid the brackish waters of the River Platte, the trains camped on the small creeks and rivers that flow into the Platte. It was these lesser streams that contained the cholera laden waters. It is surmised that the reason the outbreak was not noted is the wagon trains did not stop rolling west. They buried their dead and continued the journey. That it was not widely known in the east can be attributed to the slow movement of information, mail and or gossip from a sparsely settled west to the cities of the east. The wagons had to continue west to clean waters to rid themselves of the dangers of cholera.

At the forks of the Platte, travelers on the south side of the river had to cross the South Platte, known for its treacherous channels and alternating quick sands. In addition to the dangers presented by the river the weather could be violent, with hail, torrential rains, the occasional tornado and the ever present challenge of the wind.

Benjamin Franklin Bonney described a severe thunderstorm that occurred at night in the vicinity of the Platte River forks, “oxen bellowing, children crying, men yelling and thunder rolling like a constant salvo of artillery”. The Bonney party chained the oxen to keep them from stampeding, the loss of draft animals was but another of the dangers faced by the travelers.

Windlass Hill was a name not known to the travelers on the Oregon Trail. To them it was the 300 foot high hill with a 25 degree slope that they had to get a wagon down without mishap. Once down they proceeded to Ash Hollow for a short rest for the travelers and their animals. Nathan Pattison would bury 18 year old Rachel here saying she had taken sick in the morning and died that night. Ash Hollow would be her final resting place.

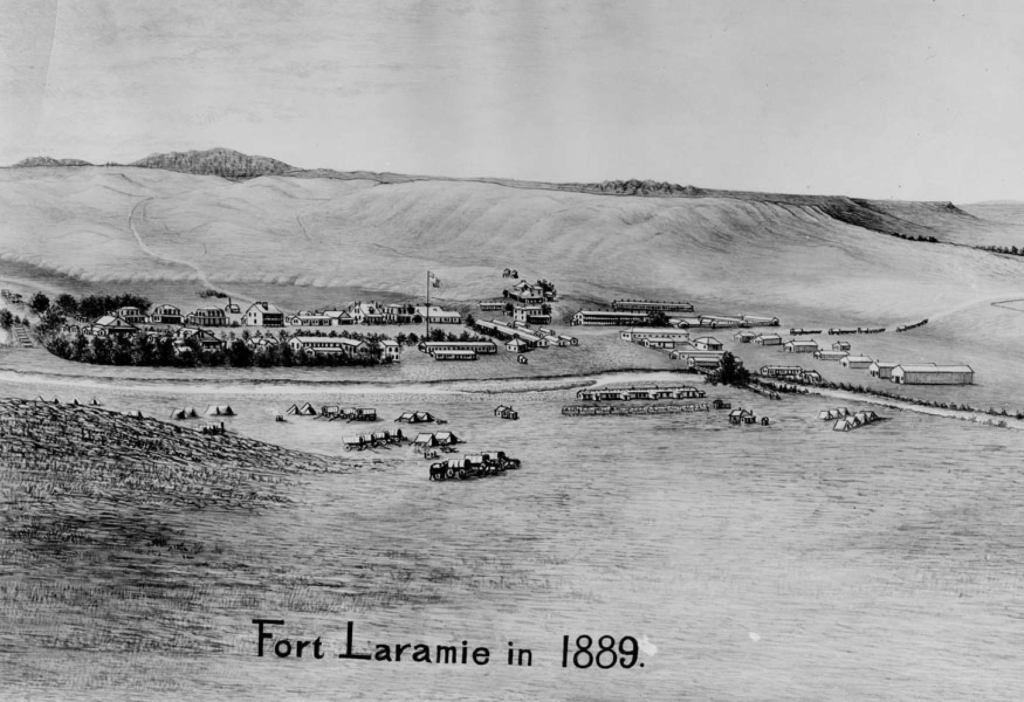

The landmarks are now rock formations that break the monotony of the flat dry plains Courthouse Rock, Jail Rocks and Chimney Rock. The land becomes drier as they proceed west across the short grass prairies. Scotts Bluff stood in the way of passage and the route detoured through Robideau Pass and later through Mitchell Pass. Scotts Bluff is now but a lingering memory as the train continues the pace of the plodding oxen towards Fort Laramie. At Fort Laramie they would finally leave the horror of Cholera and the contaminated waters of the Platte behind them.

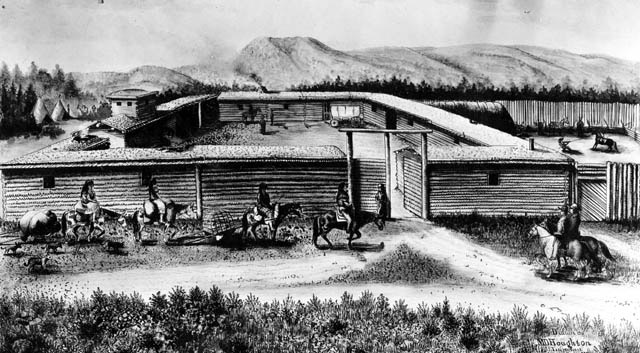

A former fur trading post named Fort John was purchased by the US Army in 1848 to help protect the travelers on the trail, re-named Fort Laramie it would be the last US Army post on the Oregon Trail. Prior to its purchase by the Army it was a trading post that offered some goods for sale at very high prices; Sugar @ $1.50 per pint and Superfine Flour @ $1.00 per pint or $40.00 per barrel. One migrant commented that “everything you buy costs 4 times its worth and everything you sell brings perhaps one tenth its value”.

Leaving Fort Laramie the trail followed the North Fork of the Platte as it curled around the north flank of the Laramie Mountains. Taking a right turn at the junction of the Sweetwater River, the trail wends its way past Independence Rock, crossing the Sweetwater several times before it reaches South Pass. As the trail slowly sapped the strength of the draft animals, more and more objects were ejected to lessen the weight of the wagons. Many tears were shed on the Sweetwater as heirlooms were simply abandoned as the need of the oxen had to take priority over human desires. The Devil’s Gate was but another treacherous passage with its narrow path completing the transition from prairie grass lands to the sagebrush covered foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

South Pass is a 25 mile wide saddle on the continental divide with the Wind River Range to the north and the Antelope Hills to the south. At South Pass the travelers enter Oregon Territory, they have come just under half way to their destination, and it is now the fourth of July.

The Rocky Mountains constituted a major obstacle to passage to the west coast of North America. The trail blazed by Lewis and Clark could not accommodate wagon traffic. The deserts of the southern routes were not without its share of dangers; insufficient water and hostile Indians. Although no easy trek, at 7,412 feet South Pass did offer a route through the formidable barrier that the Rocky Mountains represented.

The existence of the pass was well known to the Native Americans but unknown to the European/Americans. It was accidentally “discovered” due to ongoing conflicts with some of the northern tribes.

In June of 1812 members of Astor’s Fur Company left Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia River to report to Mr. Astor awaiting them in St. Louis. In an effort to avoid an Indian conflict Robert Stuart and 7 others started drifting south along the spine of the Rocky Mountains. After several blunders and near disasters in their effort to stay clear of the Indians, their travels took them to South Pass, November of 1812. It was only after traveling some distance down the SweetWater River that they realized they had crossed the Continental Divide. The party would winter on the North Platte and arrive in St. Louis in April 1813. Although Robert Stuart provided a well defined map and a journal of the trip, the pass was ignored for several years.

Employees of The Rocky Mountain Fur Company, founded by William Henry Ashley and Andrew Henry “rediscovered” South Pass as part of a fur trapping expedition up the SweetWater River in 1824. The following year, 1825, Ashley’s company would establish a trading post on Utah Lake located several miles south of the Great Salt Lake.

In 1832, Army Captain Benjamin Bonneville would lead a train of 20 wagons and 110 men over South Pass and establish Ft. Bonneville on the Green River, proving that wagons could pierce that barrier, that there was a way across the Continent… The stirrings of a Continental United States and the dreams of “Manifest Destiny” were now a distinct possibility.

South Pass is a thirty five mile wide sagebrush covered swale in the Central Rocky Mountains and was once the center of traffic to and from the western US. It provided a route that wagons could cross, that dreams could surmount in an effort to begin anew in the west.

July 1836 Marcus Whitman, his wife Narcissa, Henry and Eliza Spaulding crossed South Pass on their way to the Oregon Country to establish missions among the various Indian Tribes.

Between the years 1841 when the first organized wagon train crossed the continent and 1869 when the Trans Continental Railroad offered an alternative to the long and often irksome travel; upwards of half a million people crossed the Continental Divide at South Pass.

Several of the steeper grades the trains encountered between the Platte River and the summit of South Pass were often named “Heart Break Hill”. This is where the immigrants were forced to lighten the wagon in order to conserve their draft animals’ strength for the rest of the arduous journey. Heirlooms were often left in the dust as the reality of the climb to the Continental Divide became more apparent.

One individual said to a wagon master, “it’s Heaven to be here but Hell to get here”. The wagon master replied, “If you think this is Hell, the real test lies ahead. For sure it is not strung out along the Sweet Water”.

The Fourth of July brought a warning from the wagon masters, failure to cross South Pass by the Fourth of July put the train in danger of being trapped in early snows in the Blues of the Oregon Country or the craggy Sierras of California.

They find good water at Pacific Springs but the Big Sandy River is fraught with alkali that makes animals and people sick. With little choice the travelers water the stock as sparingly as possible and make their way to Fort Bridger and the clean waters of the Green River. At Fort Bridger the travelers could buy some supplies but the post offered a black smith shop which was even more needed than supplies.

Bridger’s trading post marked the split in the trail where the Mormon Trail turned into the Salt Lake Basin. Here the trains often were forced to deal with the shrinking wood in wagon wheels and spokes allowing them to come apart. The common treatment was to boil the complete wheel in linseed oil, but as oil was in short supply they had to content themselves with swelling the wheels and hubs by boiling them in water mixed with bear grease. It was a temporary fix at best.

As the trains left Bridger’s trading post they skirted, then crossed the southern end of Commissary Ridge that created the divide between the Green and Bear Rivers. The travelers followed the Bear River to Peg Leg Smith’s small post he erected in 1848. Leaving Smith’s post behind, the travelers were delighted with the series of springs that bubbled to the surface, Hooper, Steam Boat and Soda Springs. This was the travelers’ first experience with geysers and steam vents, to add to the excitement many found the springs tasted like beer. Wives found the water to be sufficient to raise bread, this helped to stretch the leavening agents the migrants carried.

Fort Hall was erected by Nathaniel Wyeth in 1834 and sold to the Hudson Bay Company in 1837. A train entered Fort Hall in the summer of 1842 that decided to trade wagons and teams for pack horses on advice of the chief factor at Fort Hall. Captain Grant maintained that wagons could not traverse the Blue Mountains and tried to persuade the migrants to trade their wagons and teams for pack horses. Dr. Marcus Whitman by contrast maintained that wagons could cross the Blue Mountains as he had already taken a wagon over. Once over the Blues it was possible to travel all the way to The Dalles on the Columbia River. Dr. Whitman sent his emissary, a convert to Christianity, Chief Stickas to pilot the train over the Blues.

From Fort Hall the trail follows the Snake River past American Falls, Massacre Rocks and Coldwater Hill near present day Pocatello, Idaho. The California Trail turned south to follow the Raft River south away from the Snake. The parting of the ways was always a tearful event as people who had formed strong bonds would say goodbye, many to never hear from them again.

Traveling west along the south shore of the Snake River the migrants pass Cauldron Linn Rapids and Shoshone Falls, the Thousand Springs and Salmon Falls. An Indian fishery at Salmon Falls meant they could trade with the Indians for fresh and dried salmon, a welcome change from the diet of pilot bread and bacon. Hot, dry and dusty, the trail is sandy and sage covered with little grass. The north shore beckons but steep bluffs force the train to stay on the south shore until they come to the Three Island Crossing.

A serene looking place until you watch the current as it speeds between the islands. It is then they understand that this place must be respected. The swift current and deep channels between the islands made this crossing one of the most dangerous. Over the years it would claim many lives, animal and human as well as the loss of wagons and supplies. All could be swept away in the swift currents fueled by snowmelt from the surrounding Rocky Mountains.

Slowly, relentlessly the train moves west, from Three Island Crossing the train follows the north shore of the river as they work their way toward Fort Boise. At Bonneville Point they get their first view of the lush Boise River Valley. Fort Boise, established in 1834 by the Hudson Bay Company sits nestled in the Boise River Valley near the confluence of the Boise and Snake Rivers. A short stay at Fort Boise was the order of the day as the Blue Mountains and its trials awaited the travelers. As they crossed the Snake River for the last time, they were unaware that the land they traversed here would be the future state of Oregon.

The tale of Moore’s Hollow is part fiction, part truth and just plain old human frailty. I relate this story even though it may not be altogether true, but that it reflects the feelings of many as they crossed the continent. The story takes place between Fort Boise and Farewell Bend.

Martha Moore is said to have declared “I have traveled as far as I intend. Mr. Moore, we either stop here or you may continue alone. I have driven my stake in the ground and the children and I will go no further.” As it turned out, it was a good choice, the natural grass of Moore Hollow made good hay and as they planted grain in later years, the Moore’s became financially secure by trading with the passing trains.

To be clear, this was not an isolated event as members of the trains dropped off due to many factors; a damaged wagon, the loss of draft animals, and sometimes just the day to day drudgery of the trail or as in the case of Martha Moore, just plain human frailty.

Farewell Bend, where the Snake River begins its journey through Hell’s Canyon is a place of rest before the travelers start up the narrow canyon of the Burnt River. It is now August, how could it be so hot and be snowing in days. The wagon master knows what lies ahead and is not willing to tarry on the Snake.

The Burnt River runs down a narrow canyon with steep hills that ran right to the river bed and a switchback stream that had to be crossed time and again. Agnes Stewart lamented,” Nothing but hills and hollows and rocks. Oh dear, if we were only in the Willamette Valley or wherever we are going, for I am so tired of this…” It was this kind of despair that drove Martha Moore to her decision.

Coming out of the canyon of the Burnt River, the train follows Pleasant Creek to Flagstaff Hill, the divide that separates the Burnt River drainage from the Powder River Valley. In the early years of the trail, Lone Pine camp area welcomed the travelers to the Powder River Valley. Unfortunately this Ponderosa Pine would fall to later travelers rather than use the abundant sage brush for fuel.

NOTE: The Oregon Trail Interpretive Center is located near Baker City, Oregon located in the south end of the Powder River Valley. To the west lay the lofty heights of the Blue, down the center of the valley is grassland while to the east a sage covered ridge overlooks the grand view of this little valley.

A hard pull as the train climbs Ladd Hill, over the crest the downhill side follows a fast moving creek that flows down Ladd Canyon into the Valley of the Grand Ronde. It is here that the guide Dr. Whitman promised joined us. The evening before they started to cross the Blues, their Indian guide Stickas reminded the travelers to, “Prepare your axes for you will need them tomorrow.”

The Blue Mountains are heavily forested, a maze of ridges intersected by steep walled canyons. These determined people cut the trees to clear wagon axles and moved boulders in order to get through the Blues. Frosty mornings made them aware that delaying could be lethal. Emigrant Springs heralded a near end to the making of a wagon road. This first train used Poker Jim Hill to get off the steep west side of the Blues. From the top the silver thread of the Columbia River and a silhouette of Mt. Hood are visible.

There were three trails off the Blues, the southern route was Poker Jim Hill, the center route dropped off at Dead Man’s Pass and the third route, the most northerly took the travelers into the present day town of Weston, Oregon.

Present day Interstate 84 drops off the Blues in a series of switchbacks stretching for 5 miles with very steep grades. It is no wonder that getting off the Blues was cause for celebration.

Once off the Blues the train returned to the plodding pace of the oxen crossing the Umatilla River then following the Columbia River west. The trail leaves the river and cuts south to avoid the steep canyons the small streams cut into the high plateau, Upper Well Spring, crossing the John Day and Deschutes Rivers. Here they re-enter the Columbia River gorge traveling west along the south bank of the river. Late September and the travelers begin to feel the winds that flow off the Pacific through the river’s great gorge.

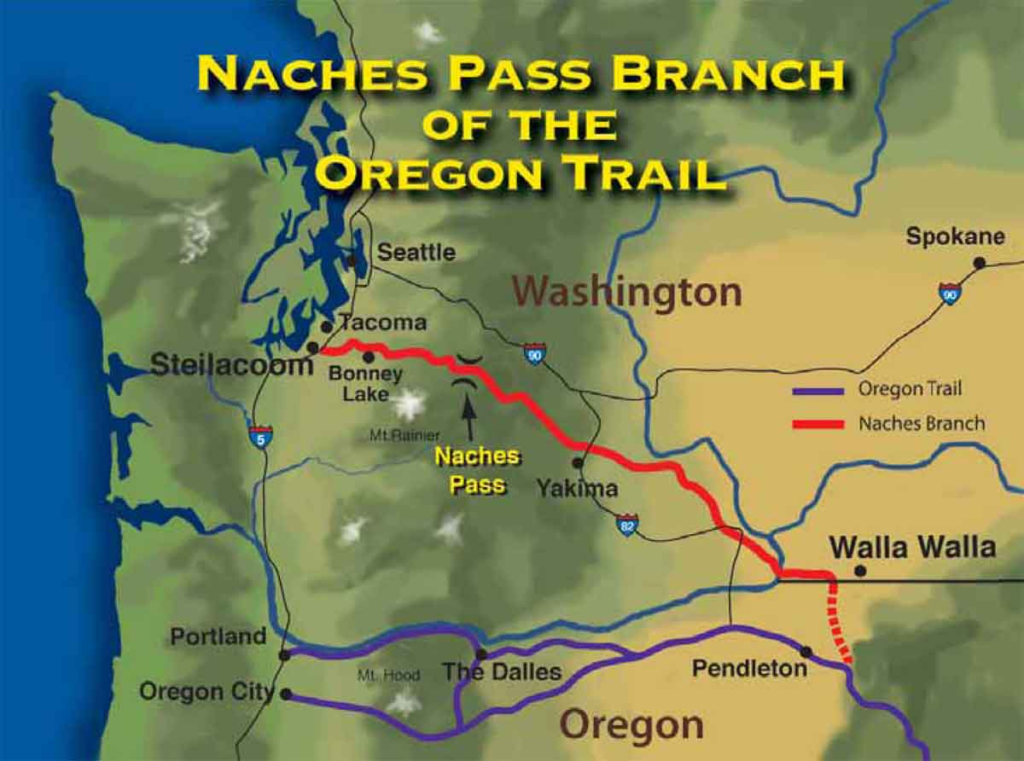

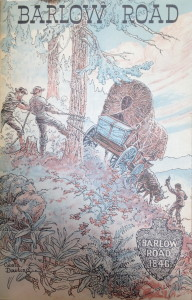

Excitement begins to rise from the weary travelers, the Dalles are in sight! The wagon road ends at Chenowith Creek; from here some float wagons down the river on rafts while others drive the stock over little known Lolo Pass. This trail wound along the north side of Mt. Hood but would be replaced by the Barlow Road in 1846. This route traversed the south side of Mt. Hood.

The Barlow Road stands out as one of the most notorious parts of the Oregon Trail. It sits on the shoulder of Mt. Hood, Laurel Hill is one of its more sinister stretches.

Laurel Hill was one of the most dangerous descents of the entire Oregon Trail. It would consume livestock, wagons and lives. This steep stretch of the Barlow road was considered a cheap alternative to the costly trip by ferry down the Columbia River.

Travel through the Gorge was filled with rapids and one especially dangerous whirlpool. Many decided to chance the Road rather than chance the Gorge. Both were fraught with danger, the road with its steep grades and the river with its rapids and whirlpools.

Laurel Hill was so steep that wagons had to be let down the grade with block and tackle. The problem arose when the rigging failed under strain, allowing the wagon to careen down the hill and crash. Many claim to this day that the graveyard at the bottom of Laurel Hill is haunted by the ghosts of pioneers whose lives were snuffed out on Laurel Hill.

The journey from The Dalles to Oregon City was anti-climatic after the trials and tribulations of the trek from Independence some 2,000 miles away.

Epilogue: This pattern of migration would continue throughout the 19th century. Trails diverted from established trails and other routes were established. The railroad would burst on the scene and bring many more to the wonderland of the west. The sale of property along the new laid tracks sold to settlers to meet bond payments and lay more track west enhanced this drive. The Trans-Continental railroad dream of Lincoln would finally cement the dream of a Continental United States. America stretched from sea to shining sea, it now claimed its heritage from the Corps of Discovery, but it was the lowly ox that made it all happen.