Featured Image: Statue of Po’pay by Cliff Fragula in the US Capitol Building Visitors center.

Po’pay is an Anglicized proliferation of the original Spanish, Po’pe’

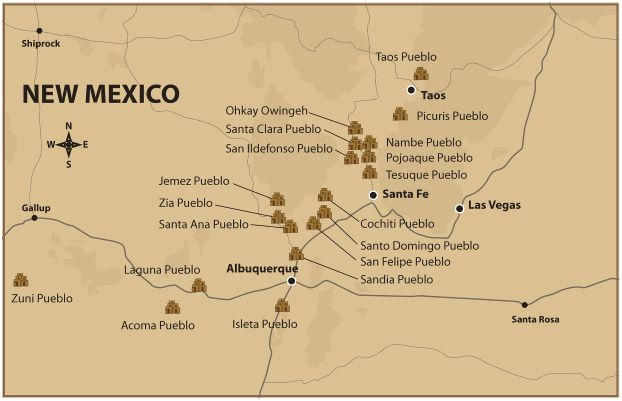

August 10, 1680 the pueblo populations of 11 different Pueblos rose up in rebellion against the oppressive Spanish ruling class. The Pueblo peoples would drive the Spaniards out of Nuevo Mexico for 12 years before the Spaniards could return to control the various tribes and pueblo populations. In their efforts to reestablish Spanish rule, they were but marginally successful.

The 1680 revolt had its beginnings in 1540 when Francisco Vasquez de Coronado waged war against 12 or 13 Tiwa Pueblos along the Rio Grande River Valley in the Tiguex War fought during the winter of 1540-41. Coronado commandeered a pueblo for his headquarters and shelter for his men by ousting the native population with little more than the clothes on their back and demanded supplies were to be surrendered to Coronado’s foragers by all the surrounding pueblos. When supplies grew short the Indians retaliated; when Coronado attacked they abandoned their pueblos and retired to a mesa top stronghold. When the Indians ran out of water they tried to escape in darkness. Discovered by the Spaniards, the Indian men as well as some of the women were killed, the rest of the women were taken as slaves.

Coronado would make his historic crossing of the plains in 1541 chasing the myths of a “City of Gold”. His return to the Rio Grande Valley would revive the war with the natives; they would wage guerrilla warfare throughout the winter of 1541-42 driving him to return to Mexico in April 1542. It would be 39 years before the Spaniards would return to Nuevo Mexico, but a pattern of conflict had been established that would continue.

Juan de Onate arrived in Nuevo Mexico as governor in 1598 beginning the process of colonization, exploration and exploitation. From its beginning the colonial settlement began to exploit the native population through a labor system called “Encomiendas” that took control of the irrigation system and forced the Indians to contribute labor and food stuffs. Onate would put down a revolt at Acoma Pueblo in 1599 (the Acoma Massacre) with brutal force, sentencing all males over the age of 25 to have their right foot amputated. In addition to bearing the burden of supporting these Spanish invaders, the Pueblo peoples were extremely agitated with the Spanish interference in their native religions.

Franciscan priests would baptize 7,000 Pueblo Indians in 1608 to forestall a move by the Spanish Crown to no longer support the missions and settlements in Nuevo Mexico. The friars were tolerant of the native religions for a while but during the 1660’s began to restrict the Kachina dances and seizing Indian religious artifacts, while forbidding the use of hallucinogens in their religious ceremonies. Anyone who moved to interfere in the abuse of the Indians was often charged with Heresy and tried before the Inquisition.

A severe drought and raids by the Apaches brought famine to the pueblos during the early 1670’s. Increased interference in native religious practices and the drought induced famine among the Indian population only fueled the Pueblo people’s anger. In 1675 the arrest of 47 Pueblo medicine men accused of “sorcery” were tried. 4 were sentenced to hang; three were hanged while one committed suicide. The rest were publicly whipped and sent to prison. The northern Pueblo leaders marched in force on Santa Fe forcing the governor to release the prisoners. One of the released prisoners was named Po’pe.

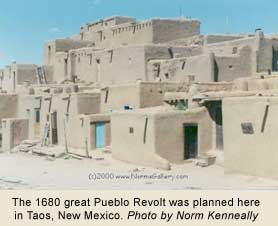

Po’pe retreated to Taos Pueblo, there he began to seek support for a revolt after his release; a natural occurring drought would aid him in his efforts. He promised that when the Spaniards were driven out the old Gods would return and the drought would end. To that end all vestiges of the Catholic invaders were to be destroyed. The churches, crosses and Christian religious items were to be burned; this included all livestock, farm animals and fruit trees. He advocated a complete return to a pre-Spanish existence, a return to native religious practices, returning to traditional native marriage practices, farming in the traditional manner, avoiding the planting of wheat and barley. This he promised would end the Spanish control allowing a return to the old ways.

An agreement to attack and drive out the Spaniards was finalized during the spring and summer of 1680. Most of the Northern Pueblos joined in the rebellion including the far flung pueblos of the Zuni and Hopi people. In order that the pueblos all rise up on the same day, Po’pe sent all the participating pueblos a knotted cord, they were to untie one knot per day, the final knot was to be the day of the revolt. That day was to be August 11, 1680. The date of the uprising was discovered by the Spaniards but Po’pe decided to start the revolt one day early, August 10. The Zuni and Hopi pueblos did not get the order but carried out their original orders on August 11.

On the morning of August 10, 1680 the Indians numbering about 2,000 with a few Apache and Navajo warriors first stole as many of the horses they could find to keep the Spaniards from fleeing. They then raided the smaller settlements killing approximately 400 men, women and children plus 21 Franciscan missionaries; the survivors fleeing to the Capital at Santa Fe or further south to Isleta Pueblo below Albuquerque which did not participate in the revolt.

All the settlements had been destroyed and the capital at Santa Fe under siege by August 13. On August 21st with the water supply cut off, the governor led a desperate foray that forced the Indians to retreat with heavy losses. Before the Indians could regroup, the Governor, Antonio de Otermin led the survivors out of Santa Fe retreating south along the Rio Grande. The Pueblo people would shadow the Spaniards as they retreated south but did not attack. The Spanish survivors that sought refuge at Isleta Pueblo began to retreat further south as well on August 15. The two groups of refugees numbering 1,946 would merge at Socorro on September 6. A Spanish supply train would escort the survivors to El Paso del Norte; the Indians did not interfere in their retreat from Nuevo Mexico.

The medicine man Po’pe would be betrayed by his prophecy as the drought continued and raids by the Apache and Navajo increased. He was deposed and subsequently faded into obscurity. An aborted re-entry to Nuevo Mexico by Governor Otermin in November of 1681 was met with a determined Pueblo people to resist the return of the Spanish.

French activity to the east and the need to construct defenses against the increasing raids by the Apache and Navajo would force the reconquest of Nuevo Mexico. Diego de Vargas would return to Santa Fe in August 1692. It is surmised that Po’pe died shortly before.

The pattern of conflict between the Spaniards and the Native Americans of what is now the South Western United States that began in 1540 would continue after the rebellion of 1680 but with forbearance for the Native Religions and the practice thereof. As the Pueblo people settled into a coexistence with the Spanish population, the restive Apache and Navajo increased their raids and a pattern of conflict that would continue into the early 20th century with the subsequent Mexican government. The Pueblo people were pacified by the time Phil Kearney conquered New Mexico in 1850.