On 24 June 1948 Soviet forces initiated a blockade of Berlin. This blockade prevented the shipment of food, fuel, coal and other necessities into the Allied controlled areas of the city.

The purpose behind the blockade was to undermine the Allied position in Berlin and in Germany overall. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin told visiting Bulgarian and Yugoslavian delegations in early 1946 that Germany must be both Soviet and communist. Until the blockade began in 1948, the Truman Administration had not decided whether American forces should remain in West Berlin after the establishment of a West German government, planned for 1949.

After a 9 March meeting between Stalin and his military advisers, a secret memorandum was sent to Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov on 12 March 1948, outlining a plan to force the policy of the western allies into line with the wishes of the Soviet government by “regulating” access to Berlin. With this memo, the outline of the blockade was in place. The Soviets were planning on taking advantage of the lack of negotiated ground and water routes into Berlin.

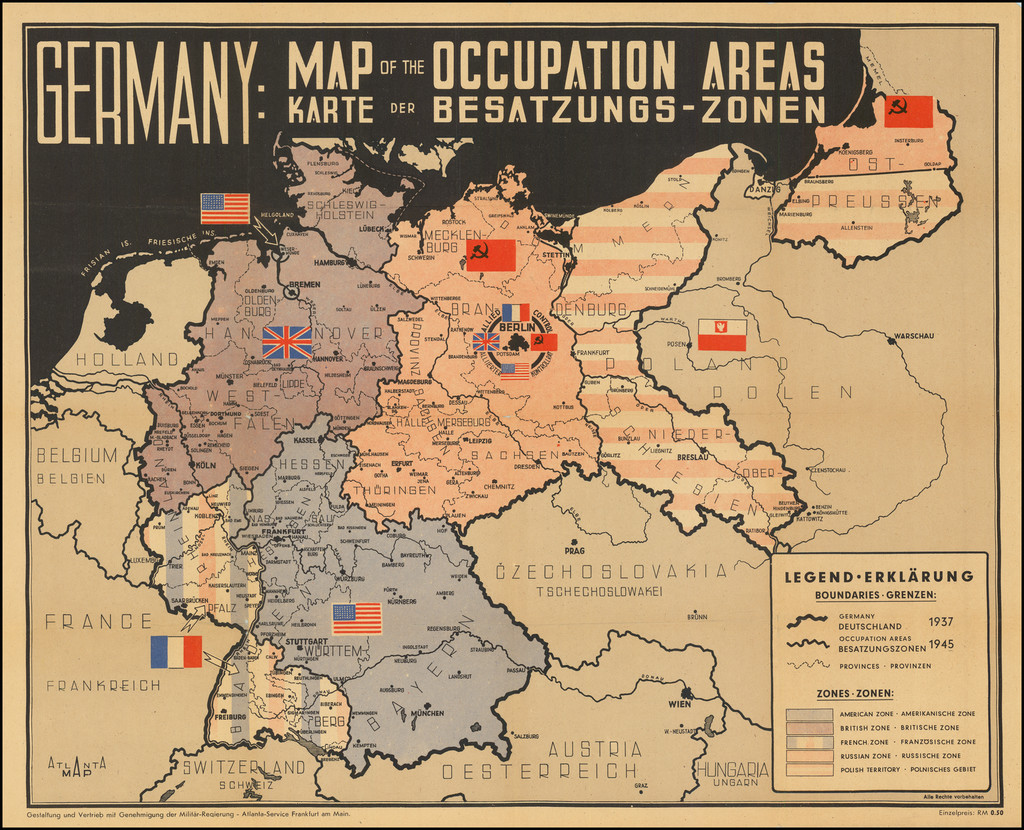

On 25 March 1948, the Soviets issued orders restricting Western military and passenger traffic between the American, British and French occupation zones and Berlin. These new measures began on 1 April along with an announcement that no cargo could leave Berlin by rail without the permission of the Soviet commander. Each train and truck was to be searched by the Soviet authorities. On 2 April, General Lucius Clay, the US commander in occupied Germany, ordered a halt to all military trains and required that supplies to the military garrison be transported by air, in what was dubbed the “Little Lift.”

The final piece of the puzzle fell into place with the introduction of the Deutsche mark by the Allies in June of 1948. The Soviets had been manipulating the value of the Reichsmark as a method of economic control and knew they couldn’t do the same with the new currency.

On 24 June, the Soviets severed land and water connections between the non-Soviet zones and Berlin. That same day, they halted all rail and barge traffic in and out of Berlin. The next day the Soviets stopped supplying food to the civilian population in the non-Soviet sectors of Berlin. The Blockade was on.

General Clay summed up the reasons for not retreating in a cable on June 13, 1948, to Washington, D.C.:

There is no practicability in maintaining our position in Berlin and it must not be evaluated on that basis… We are convinced that our remaining in Berlin is essential to our prestige in Germany and in Europe. Whether for good or bad, it has become a symbol of the American intent.

Believing that Britain, France, and the United States had little option other than to acquiesce, the Soviet Military Administration in Germany celebrated the beginning of the blockade. General Clay felt that the Soviets were bluffing about Berlin since they would not want to be viewed as starting a Third World War. He believed that Stalin did not want a war and that Soviet actions were aimed at exerting military and political pressure on the West to obtain concessions, relying on the West’s prudence and unwillingness to provoke a war. General Curtis LeMay, commander of United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), reportedly favored an aggressive response to the blockade, in which his B-29s with fighter escort would approach Soviet air bases while ground troops attempted to reach Berlin; Washington vetoed the plan.

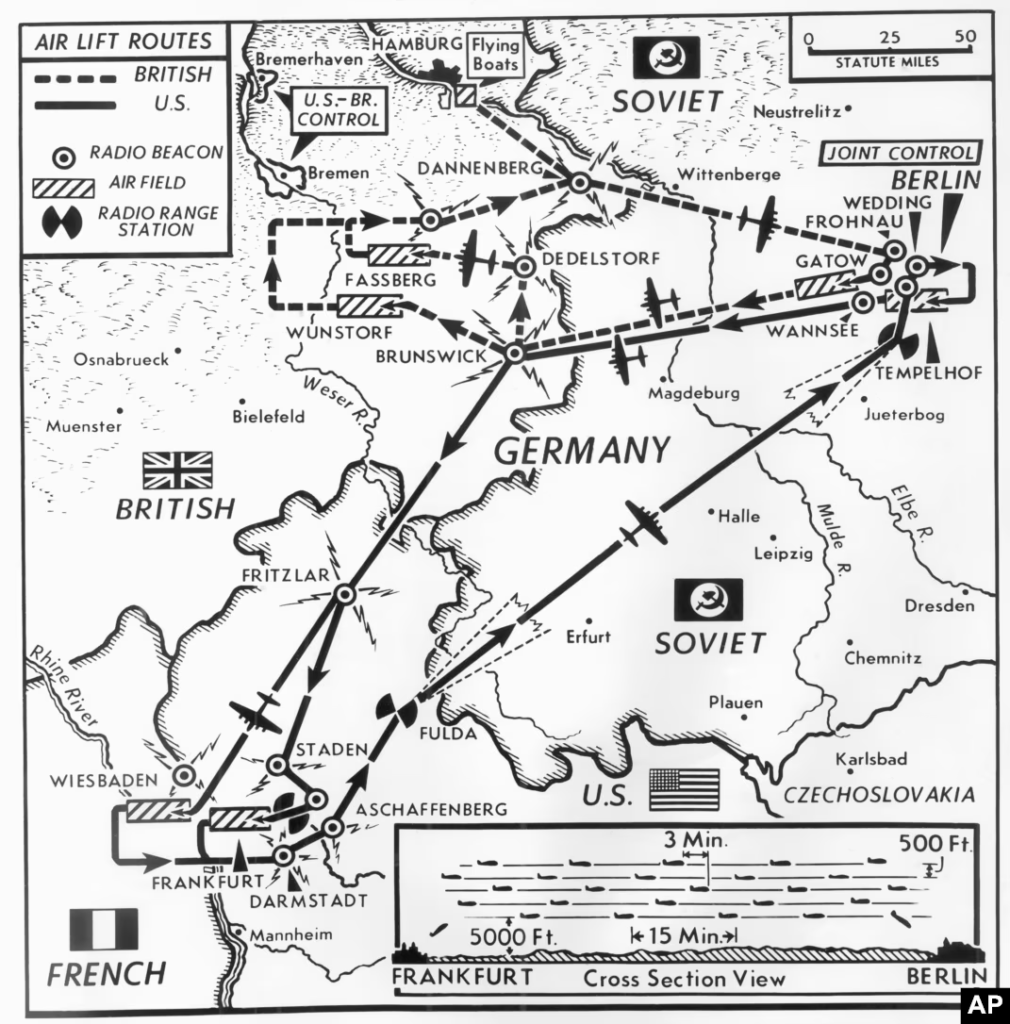

Although the ground routes had never been negotiated, the same was not true of the air. On 30 November 1945, it had been agreed in writing that there would be three twenty-mile-wide air corridors providing free access to Berlin. Additionally, unlike a force of tanks and trucks, the Soviets could not claim that cargo aircraft were a military threat.

The airlift option critically depended on scale and effectiveness. If the supplies could not be flown in fast enough, Soviet help would eventually be needed to prevent starvation. Clay was told to take advice from General LeMay to see if an airlift was possible. “We can haul anything,” LeMay responded, after initially taken aback by the inquiry, “Can you haul coal?”

Thus was born Operation Vittles, the largest airlift in history.

The Western Allies organised the Berlin Airlift from 26 June 1948 to 30 September 1949 to carry supplies to the people of West Berlin, a difficult feat given the size of the city and the population.

American and British air forces flew over Berlin more than 250,000 times, dropping necessities such as fuel and food, with the original plan being to lift 3,475 tons of supplies daily. By the spring of 1949, that number was often met twofold, with the peak daily delivery totalling 12,941 tons. Among these, was the work of the later concurrent Operation Little Vittles in which candy-dropping aircraft dubbed “raisin bombers” generated much goodwill among German children.

Read: Gail S Halvorsen the Berlin Candy Bomber, Dead at 101

Having initially concluded there was no way the airlift could work, the Soviets found its continued success an increasing embarrassment. On 12 May 1949, the USSR lifted the blockade of West Berlin, due to economic issues in East Berlin, although for a time the Americans and British continued to supply the city by air as they were worried that the Soviets would resume the blockade and were only trying to disrupt western supply lines.

The Berlin Airlift officially ended on 30 September 1949 after fifteen months. The US Air Force had delivered 1,783,573 tons (76.4% of total) and the RAF 541,937 tons (23.3% of total), totalling 2,334,374 tons, nearly two-thirds of which was coal, on 278,228 flights to Berlin.

American C-47 and C-54 transport airplanes, together, flew over 92,000,000 miles (148,000,000 km) in the process, almost the distance from Earth to the Sun. British transports, including Handley Page Haltons and Short Sunderlands, flew as well. At the height of the Airlift, one plane reached West Berlin every thirty seconds.

Seventeen American and eight British aircraft crashed during the operation. A total of 101 fatalities were recorded as a result of the operation, including 40 Britons and 31 Americans, mostly due to non-flying accidents.