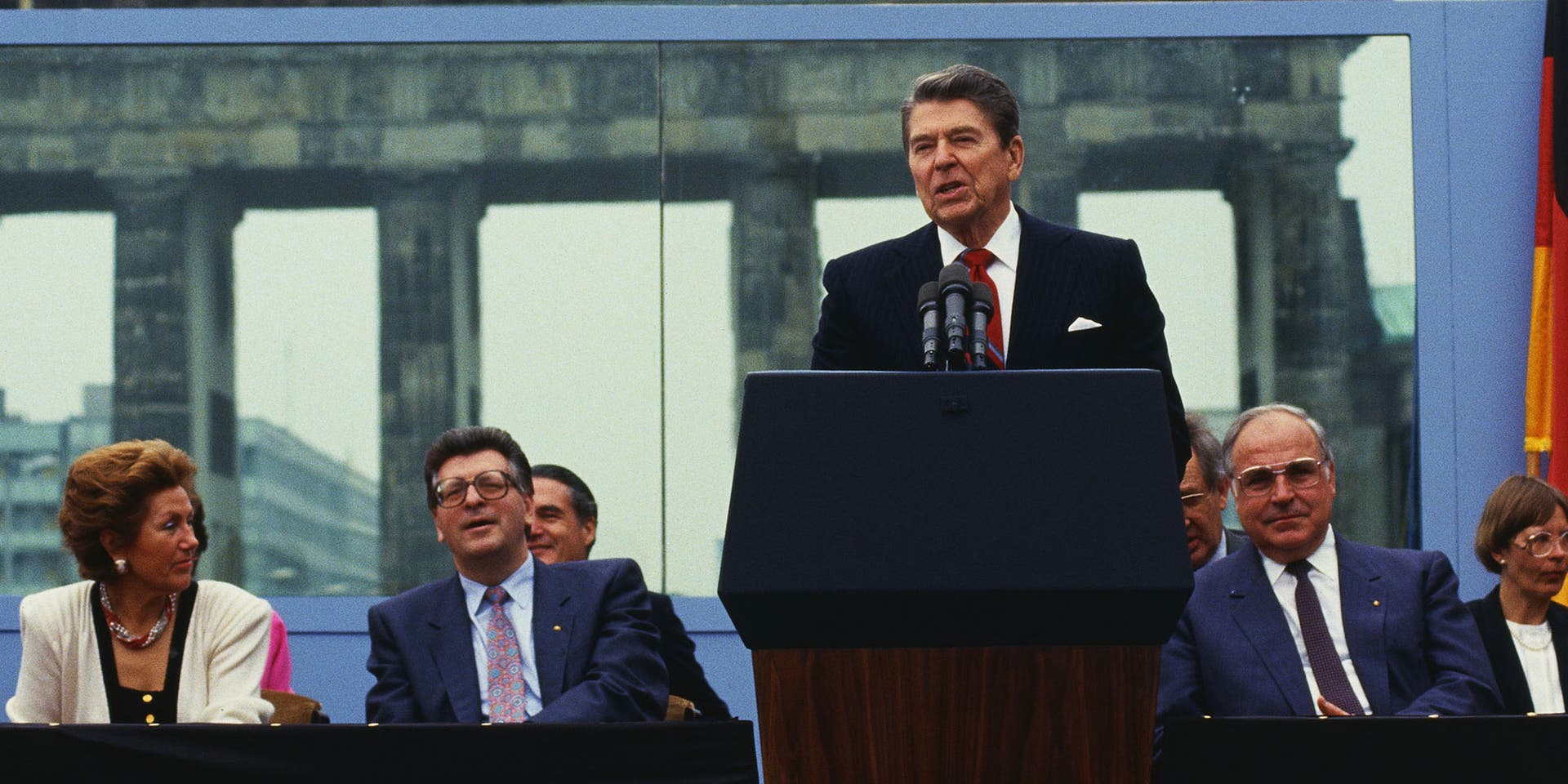

That sentence, the one in the title of this article, was spoken by President Ronald Reagan 36 years ago today at the Brandenburg Gate in (then) West Berlin. He was less than 100 yards from the wall that separated free West Berlin from the communist East.

Reagan had travelled to Berlin to help celebrate that city’s 750th anniversary. The Wall had been up for almost 26 years at that point. It had been built to stem the tide of East Germans who wanted out of the Soviet dominated East Germany. The wall was more than just a physical barrier. It also stood as a vivid symbol of the battle between communism and democracy that divided Berlin, Germany and the entire European continent.

The wall’s origins traced back to the years after World War II, when the Soviet Union and its Western allies carved Germany into two zones of influence that would become two separate countries, respectively: the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). Located deep within Soviet-controlled East Germany, the capital city of Berlin was also split in two.

Over the next decade or so, some 2.5 million East Germans—including many skilled workers, intellectuals and professionals—used the capital as the primary route to flee the country, especially after the border between East and West Germany was officially sealed in 1952.

Seeking to stop this mass exodus, the East German government closed off passage between the two Berlins during the night of 12 August 1961. What began as a barbed wire fence, policed by armed guards, was soon fortified with concrete and guard towers, completely encircling West Berlin and separating Berliners on both sides from their families, jobs and the lives they had known before. Over the next three decades, thousands of people would risk their lives to escape East Germany over and under the Berlin Wall, and some 140 were killed in the attempt.

On June 12, 1987, standing on the West German side of the Berlin Wall, with the Brandenburg Gate at his back, Reagan declared: “General Secretary Gorbachev, if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate. Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate.” Reagan then waited for the applause to die down before continuing. “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!”

Reagan’s tactics were a departure from his three immediate predecessors, Presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, who all focused on a policy of détente with the Soviet Union, playing down Cold War tensions and trying to foster a peaceful coexistence between the two nations. Reagan dismissed détente as a “one-way street that the Soviet Union has used to pursue its own aims.”

Reagan’s speech initially received relatively little media coverage, and few accolades. Pundits viewed it as misguided idealism on Reagan’s part, while the Soviet news agency Tass called it “openly provocative” and “war-mongering.”

The Berlin Wall remained up for a bit more than two more years. On 9 November 1989, the head of the East German Communist party, Egon Krenz, announced that citizens could now cross into West Germany freely. That night, thousands of East and West Germans headed to the Berlin Wall to celebrate, many armed with hammers, chisels and other tools. Over the next few weeks, the wall would be nearly completely dismantled. After talks over the next year, East and West Germany officially reunited on October 3, 1990.

In the aftermath of the Berlin Wall’s fall, the reevaluation of the speech began. It was viewed as a harbinger of the changes that were then taking place in Eastern Europe. In the United States, Reagan’s challenge to Gorbachev has been celebrated as a triumphant moment in his foreign policy, and as Time magazine later put it, “the four most famous words of Ronald Reagan’s presidency.”