The Supreme Court vs. the Administrative State

Adam J. WhiteSeptember 2024 for commentary.org

Forty years ago, the Supreme Court ruled that judges should defer to regulators when they offer reasonable interpretations of ambiguously worded laws. As a matter of legal doctrine, the case in question—Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council—was important from the start. But for a long time, the importance of what came to be known as “Chevron deference” was limited to the world of regulatory litigators, agencies, judges, and administrative-law professors. In the larger scheme of things, it was a fairly mundane subset of a very mundane subject.

Then, about a decade ago, everything changed. President Obama’s second term unleashed a wave of unprecedented regulatory fiats that depended on “Chevron deference” for their implementation. Obama’s “Clean Power Plan” would transform the nation’s energy industry. An “Open Internet Order” would dras-tically regulate Internet service providers to make them more “neutral.” A “Clean Water Rule” would dramatically extend federal regulatory power over farms and other privately owned lands by deeming even dry lands “wetlands.” And the programs called DACA and DAPA would unilaterally transform immigration policy. President Obama, facing a hostile Republican House majority, could not pass legislation for any of it. But, he told the American people in 2014, “I’ve got a pen, and I’ve got a phone.” That pen and that phone relied on Chevron deference to get things done.

The Obama administration’s final years put the American political and judicial systems on notice that federal agencies had reached unprecedented levels of power, ambition, and gravity.

An old term rose anew to describe them collectively. The term was the “administrative state.” Its governing doctrine and the source of its power was Chevron deference, which was deployed to give agencies the power to write and implement what amounted to legislation without the actual legislative branch having the slightest say in the matter.

Conservative judges, foremost Justice Clarence Thomas, began to publish legal opinions rethinking administrative law from the ground up, endorsing the outright abandonment of Chevron deference. Conservative intellectuals like George Will embraced and amplified this new mood of judicial assertion. Even Justice Antonin Scalia, who since the 1980s had been Chevron’s most eloquent theorist and defender, began to signal second thoughts.

The change was not simply partisan. It was an evolution in conservative legal thinking, and it began among judges and lawyers only in the early 2000s. The evolution was more a reflection of an increasingly confident conservative judicial worldview that sought to build on the ideas of textualism and originalism—ideas that urged judges to read laws for themselves to determine their meaning rather than deferring to unelected bureaucrats. Their passion for this effort was driven by increasingly implausible interpretations of old statutes by these agencies under the aggressively novel Obama administration, which sought to transform entire industries through new regulatory programs that their bureaucrats dreamed up.

The entire intellectual exercise challenging the viability of Chevrondeference—the effort to answer the question of how much agencies can and should do when the laws they are bound to enforce do not provide adequate guidance—might have developed much more slowly, in law-review articles and scattered judicial opinions. The Obama administration’s final years, with their antinomian fervor, forced the question into full public view. Ideas have consequences, but not just the intended ones. Obama literally said that “we can’t wait” for legislators to act. That assertion of power not assigned by the Constitution to any executive branch official has now met a fiery end, in a Supreme Court decision handed down in June called Loper Bright v. Raimondo.

“Chevron is overruled,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote for the Court. “Courts must exercise their independent judgment in deciding whether an agency has acted within its statutory authority.”

The decision is transformative, and for more reasons than the merely ideological. In cases over the past decade, its coming was signaled primarily by Chief Justice John Roberts, who has struggled to balance conservative jurisprudence with what might be called real-world pragmatism, notably in his highly problematic rulings on Obamacare. But even after casting the deciding vote to accept the dubious constitutionality of Obamacare—which was, in Roberts’s defense, passed by Congress and signed into law—he quickly started signaling his discomfort with the broader administrative activism Obama was embracing.

In a 2013 opinion dissenting from the Court’s decision to defer in a certain case to a Federal Communications Commission regulatory scheme, Roberts issued one of his most pointed jeremiads. “The administrative state ‘wields vast power and touches almost every aspect of daily life,’” he wrote. “The Framers could hardly have envisioned today’s ‘vast and varied federal bureaucracy’ and the authority administrative agencies now hold over our economic, social, and political activities. … ‘[T]he administrative state with its reams of regulations would leave them rubbing their eyes.’”

Roberts urged his colleagues not to defer to an agency’s view of the agency’s own jurisdiction. But he was unsuccessful in this case and had to settle for making the argument in a dissent. Two years later, he brought similar themes (in less colorful prose) to a majority opinion. That case, King v. Burwell, affirmed the Obama administration’s interpretation of Affordable Care Act and federal subsidies for insurance purchased on federal exchanges. It was a highly dubious reading of the law’s text, and the controversy over it overshadowed the chief justice’s crucial move at the outset of his majority opinion. In it, he held that Chevron deference could not apply in cases where the interpretation at issue involves “a question of deep ‘economic and political significance’ that is central to this statutory scheme.”

In oral arguments on the case a few months earlier, the Obama administration’s solicitor general had urged the Court to give Chevrondeference to the agency’s interpretation. It was then that Roberts offered an unassailable objection. “If you’re right about Chevron,” he said, wouldn’t that indicate “that a subsequent administration could change that interpretation?” In other words, if everyone is to defer to an agency’s view, and individuals and businesses and governments all change their approaches to satisfy that view—what happens a year or two or three later when a new president is elected and his bureaucrats have the opposite view?

This went at a crucial and intellectually self-negating feature of Chevron deference. If a statute is ambiguous and thus susceptible to multiple different interpretations, according to Chevron deference, a judge should defer to the agency’s reasonable interpretation…and then, two years later, defer again to the agency’s subsequent reinterpretations, as long as they too are reasonable.

With the King v. Burwell case, the problem seemed especially acute to Roberts. If the Court were to use Chevron deference to affirm the Obama administration’s interpretation of Obamacare’s subsidy provision—and then use Chevron de-ference to affirm the next administration’s possibly opposite interpretation—the entire situation would be chaos. Millions of people would have been making financial and life decisions based on the original interpretation. Federal and state governments would have been making rules based on it. Insurance policies would have been written using it. And then what? They all go poof?

The concern would appear subtly in other decisions written by the chief justice during the Trump administration when it came to about-faces at the agency level. Two cases from the Trump years stand out. First, the Court rejected the Trump Homeland Security Department’s attempt to repeal the DACA immigration policy Obama had put in place. Second, the Court turned back the Trump Commerce Department’s attempt to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census. Neither decision involved Chevron deference, and neither explicitly barred the door to an agency later attempting the same policy change. But each of those decisions were designed to place speed bumps in the road path to slow the pace of change in modern administration.

The issue, therefore, is not merely Chevron deference but the constant instability created by the rise in power and authority of the administrative state. Its capacity for wild regulatory swings from one administration to the next is an increasingly obvious and onerous problem for Americans.

For decades, business leaders have complained about the overall burden of regulation. But more recently, business leaders have become increasingly vocal about the more specific problem of regulatory change. Bank of America CEO Brian Moynihan voiced this concern, just weeks after Loper Bright was decided, on Bloomberg TV’s Wall Street Week. “In the end of the day, we are for good, clear, fair regulation,” he told host David Westin. “Give us a set of rules, let us go after it. If you keep changing the rules back and forth based on political movements, based on swings, based on personalities…that just goes on.”

Or take another recent statement from prominent business leaders. When venture capitalists Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz announced their support for Donald Trump, they framed their argument in terms of the regulatory climate surrounding cryptocurrency. They did not criticize an overabundance of rules; they criticized the lack of clear laws and, relatedly, the ability of current regulators to leverage that regulatory uncertainty to chill new investments and technologies. “So we then went to Congress to say, well maybe we can pass a law that clarifies, you know, when something’s a security when it’s a commodity,” Horowitz said, “and the administration in the form of the SEC and the FDIC…have just fought us every step of the way and using very nefarious means.”

His argument is plain. “First they refuse to issue any guidance,” he continued, and then “they’ve gone after the companies in lack of law—no law and no guidance.”1

These criticisms demonstrate that the problem with the modern regulatory environment is not simply too many regulations, but also too much regulatory uncertainty. This goes to the very roots of our constitutional order. Both Alexander Hamilton and James Madison emphasized the need for steady administration of the laws; the Federalistis replete with references to it. “What farmer or manufacturer will lay himself out for the encouragement given to any particular cultivation or establishment,” Madison asked in Federalist 62, “when he can have no assurance that his preparatory labors and advances will not render him a victim to an inconstant government?”

And from the start, these Founders knew that changes in presidential administrations would tend to exacerbate the problem. “To reverse and undo what has been done by a predecessor, is very often considered by a successor as the best proof he can give of his own capacity and desert,” Hamilton warned in Federalist 72, and wild changes from one administration to the next would produce “a disgraceful and ruinous mutability in the administration of the government.”

Hamilton and Madison prized “steady administration,” and in his opinion in Loper Bright, so does Chief Justice Roberts. At the very outset of his analysis, he quotes Hamilton’s Federalist 78: “To ensure the ‘steady, upright and impartial administration of the laws,’ the Framers structured the Constitution to allow judges to exercise that judgment independent of influence from the political branches.”

That is the key import of Loper Bright. It does not aim to prevent agencies from announcing sweeping, unprecedented new regulatory programs on the basis of vague statutes; the Court’s “Major Questions Doctrine” already accomplishes that.

Rather, it is designed to prevent agencies from constantly changing from one interpretation to another, or leveraging regulatory uncertainty under vague statutes. The theory behind Loper Bright is that over time, as more and more statutes are definitively interpreted by the courts, agencies will lose the ability to whipsaw from one policy to another, or to threaten novel interpretations under old statutes.

Loper Bright’s critics have argued that the decision will actually increaseregulatory uncertainty. Old regulatory policies that once survived judicial review thanks to Chevron deference will someday be struck down in new cases, they warn. Or new regulatory policies will spur disagreements among courts, creating a messy legal patchwork from one federal circuit to another.

The concerns have a grain of truth. Chevron’s heavy thumb on the agencies’ side of the judicial scale reduced the odds that courts would strike down new regulations. But the critics miss the bigger point. They ignore the much greater stability that Loper Bright will facilitate. If an agency’s new regulation spurs disagreement among the lower courts over how to best interpret a statute, the Supreme Court will settle the question by interpreting the statute definitively. And once the courts have settled on an interpretation, it won’t be subject to agency reversal every four or eight years upon a new administration’s arrival.

Other critics claim that Loper Bright’s reasoning conflicts with the Court’s other year-end blockbuster on presidential immunity, which found that the president can be held immune from legal sanction arising from some “official acts.” Loper Bright disempowers presidents in a bad way, critics claim, while Trump v. United States empowers them in a bad way.

Once again, the critics miss the point. The two cases, both penned by Roberts, reflect the same constitutional insight: the need for energetic, steady administration, and the dangers that arise in a world when each new presidential administration turns its aim at the work of its predecessor.

In Trump v. U.S., the Court affirmed a limited form of presidential immunity for the sake of energetic execution of the laws. Roberts warned that if the Court were to rule differently, “a President inclined to take one course of action based on the public interest may instead opt for another, apprehensive that criminal penalties may befall him upon his departure from office.” He continued: “The Framers’ design of the Presidency did not envision such counterproductive burdens on the ‘vigor’ and ‘energy’ of the Executive,” he added, quoting Federalist 70’s argument for “energy in the executive” for the sake of “steady administration of the laws.”

To the extent that Loper Bright disempowers the president, it is a reduction of his power to make laws, not to execute them. That is fully within the Constitution’s separation of legislative and executive powers, and the former’s check on the latter. Loper Bright makes the president less of a unilateral legislator. Future presidents will enjoy less discretion to interpret laws, but this will leave them with more energy to execute the laws that legislatures have written and courts have interpreted.

The Court’s other major regulatory case this year, SEC v. Jarkesy, can be understood in similar terms. Many agencies have long enjoyed discretion to choose the initial forum for litigating cases: They can either file a lawsuit in a federal trial court or undertake the initial “adjudication” before an in-house agency tribunal.

Agency adjudications, and agency officials who decide them (who are often assigned the contestable title of “administrative law judges,” though they are not appointed by the president with Senate confirmation, and they do not have judicial life tenure), have raised constitutional concerns among many of the same judges and legal scholars who criticized Chevrondeference.

In 2022, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit issued a stunning decision in the case of SEC v. Jarkesy, declaring the Securities and Exchange Commission’s in-house adjudication framework triply unconstitutional. It said first that the agency’s adjudicators were unconstitutionally appointed. Second, it found that Congress’s grant of discretion to the SEC to direct cases either to courts or to the SEC’s own tribunal was an unconstitutional “delegation” of legislative power. Finally, it said the agency’s failure to use juries in the in-house tribunal violated the Constitution’s right to trial by jury.2

A day before deciding Loper Bright, the Court decided Jarkesy. In an opinion written once again by Chief Justice Roberts, the Court agreed with the Fifth Circuit on the trial-by-jury point. “When a matter ‘from its nature, is the subject of a suit at the common law,’ Congress may not ‘withdraw [it] from judicial cognizance,’” Roberts wrote. “A defendant facing a fraud suit has the right to be tried by a jury of his peers before a neutral adjudicator.” The agency cannot simply turn off the constitutional right to trial by jury, like a light switch. To allow otherwise, he emphasized, “would permit Congress to concentrate the roles of prosecutor, judge, and jury in the hands of the Executive Branch. That is the very opposite of the separation of powers that the Constitution demands.”

Thus Jarkesy, like Loper Bright, is an attempt to re-separate the Constitution’s powers. It is not a silver bullet to end the administrative state. The SEC and similar agencies can still bring enforcements case in—get the smelling salts ready—actual federal courts. To the extent that Jarkesy reduces an agency’s power, it is simply bringing the agency back to its proper constitutional role bringing cases, not judging them.

Critics bent on denouncing the Roberts Court’s decisions in Jarkesy and Loper Bright tended to be less worried about cases that drew similar lines in the agencies’ favor. Those were heard and decided as well in this past term.

In FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, the Court rejected litigation to second-guess the FDA’s past approvals of mifepristone, the abortion pill. The Court, in an opinion written this time by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, held that the plaintiffs lacked “standing” to challenge the FDA’s decisions in court. The Constitution’s Article III empowers courts to hear certain kinds of “cases” and “controversies,” and the Court has long construed those limits as requiring plaintiffs to have “standing”—that is, to have an actual injury that was caused by the defendants and redressable by the court.

The plaintiffs here fell short of that, the justices concluded. If federal courts were allowed to adjudicate such cases against the agency, they would intrude on the executive and legislative branches’ own constitutional responsibilities. “Article III does not contemplate a system where 330 million citizens can come to federal court whenever they believe that the government is acting contrary to the Constitution or other federal law,” the Court wrote. “Vindicating ‘the public interest’ (including the public interest in Government observance of the Constitution and laws) is the function of Congress and the Chief Executive.’”

The Court issued a similar decision in yet another case, Murthy v. Missouri. The plaintiffs sought to litigate allegations that the Biden administration had unconstitutionally used social-media companies to limit online speech. The justices did not reach the merits of the claims, because they found that the plaintiffs lacked standing. And “[i]f a dispute is not a proper case or controversy, the courts have no business deciding it[.]” Such disputes, absent a plaintiff with constitutional standing to file a case, are properly left to Congress, the administration, and the court of public opinion.

Yes, ideas have consequences. The Supreme Court’s latest term proved the point twice over. Vindicating the founding generation’s constitutional vision, and vindicating modern thinkers’ ideas of how to restore the Constitution today, will have profound effects on the administrative state. To be sure, even these great decisions will have further consequences we cannot necessarily envision, for as all conservatives know, the law of unintended consequences is one of the few immutable realities of our imperfect world. But the decision’s immediate consequences are clear, crucial, and excellent. Loper Bright exemplifies the Founders’ ideal of good, constitutional government.

1 Perhaps no agency better exemplifies this problem today than the Federal Trade Commission under the leadership of Chairwoman Lina Khan, as I detailed in these pages in “The Power Broke Her,” March 2024.

2 I described the Fifth Circuit’s decision in these pages. See “Reining in the Bureaucrats,” July/Aug. 2022.

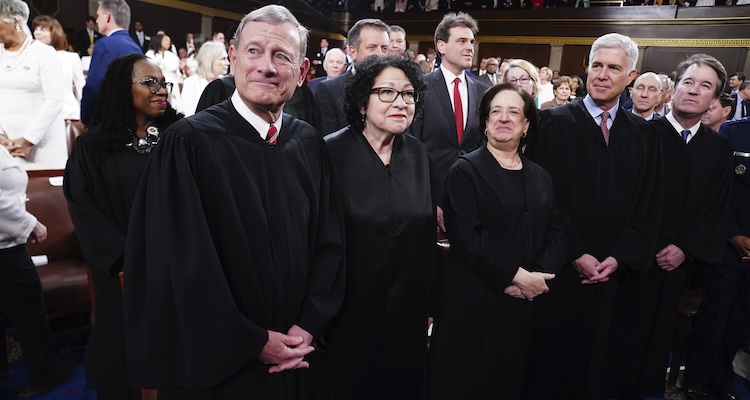

Photo: Shawn Thew/Pool via AP