Experiencing Siena in Paint, Ivory, Marble, and Gold

Brian T. Allenfor National Review

On Saturday I wrote about Siena: The Rise of Painting, 1300–1350, the Met’s lovely, inspiriting new exhibition. It’s an erudite show, too, in the finest Met tradition, so I’m doing a two-parter. Last week I wrote about the core artists — Duccio, brothers Ambrogio and Pietro Lorenzetti, and Simone Martini, not household names — and how the curators develop core themes in Sienese art. Rich color and storytelling finesse abound. That otherworldly Gothic look endures, not because the locals were clingers. Rather, the Sienese modernized Gothic style, though they stuck with much of its abstract, spiritual look. The Black Death in the late 1340s killed half of Siena’s population, whacked its economy, and froze it in its late-medieval state.

Today, I’ll write more about Sienese style as well as the show’s exquisite ivories, marble sculpture, and works in gold. The small altarpieces and parts of altarpieces by Ambrogio and Simone are divine. And what couldn’t travel to New York? Plenty. Better pack your bags for a Siena visit.

Late Gothic art, especially sculpture and painting, is an acquired taste, since we expect our art of the divinities to be orgasmic — Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa comes to mind — or aeronautic, as are thousands of Ascensions and Assumptions, or horror-movie gruesome. How many Old Master paintings have I seen of Saint Lawrence on the grill, the flayed Saint Bartholomew, and Saint Agatha with her breasts on a plate? A lot. Crucifixions aside, Siena’s paintings depict everyday people who experience God in intricate, “Believe It or Not” ways. It demands a suspension of disbelief that most can’t rouse in our secular time.

Figures are on the flat side and look like polished cartoons. There’s depth and scale, but they’re obviously contrived. Psychology and expression exist, but Shakespeare is hundreds of years in the future. Gold-leaf backgrounds glow in candlelight but are both unreal and archaizing. Sienese narrative art reminds me of silent movies, or graphic novels with text recited in our heads. And Sienese art tends to be intimate. There’s not much gigantism, and modern eyes tend to go for big.

So Rise of Painting demands close, patient looking. I love elephants and deplore killing them for ivory, but the small, ivory sculptures in the show are mighty sweet. There’s a group of them in the exhibition, too many, I thought, given that most are French. Siena was on the ancient road connecting Rome and Paris, so French panache was well known and appreciated in Siena and informed its art.

Scenes from Christ’s Passion, from around 1300, a small, four-panel ivory devotional, might have inspired Siena’s taste for small, accordion-painted altarpieces like Simone Martini’s Orsini Polyptych from the late 1320s. The ivories were portable and, as sculpture, expressed body mass, drapery folds, and motion more convincingly than old-style Gothic painting did. Before long, painters went for the same effects. And while I love ivory sculpture’s cool, creamy-gray palette, most of them would have been painted. A digital example would probably have reinforced the show’s assertion that these ivories inspired Siena’s painters.

And a section on Sienese color would have linked painting, ivories, gold backgrounds, and the exhibition’s enamel-encrusted gold chalices and reliquaries. Ultramarine, azurite, coral, ochre, jade green, burnt sienna, named after Siena, and rose pink, among a hundred others, make the art of Siena so luscious. The Met’s Chalice of Peter of Sassoferrato, from around 1341, is color-gone-wild, with a silver and gilt-silver cup, and a knob and base packed with enamel — translucent colored glass — medallions depicting saints. Goldsmiths worked closely with painters on gold-leaf backgrounds, which were often embossed or pricked with designs. Since goldsmiths and silversmiths worked with precious metals, they were high-status artists.

The chalice is in a skimpy section on gold and enamels. I would have put these objects in a section on Sienese color that also examines the aesthetics of gold backgrounds in painting.

Last week, I wrote about Martini’s set of four imaginary portraits of saints and a companion Madonna and Child from the mid 1320s. They’re great and important but, for Martini, on the austere, even severe, side. The Orsini Polyptych is, for him, characteristically snazzy. There’s angst galore in its Crucifixion and Deposition from the Cross, but other panels have gossamer and lissome moments, too, from abundantly incised gold backgrounds, pretty furniture, and dainty poses. Martini was a pioneer, we learn, of the aristocratic, suave, polished, and sometimes flamboyant International Gothic style.

Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Stories from the Life of Saint Nicholas, from about 1333, is one of the high points in The Rise of Painting. Yes, that’s Saint Nick himself, who later evolved into Santa Klaus because of his gift-giving prowess. Nicholas (270–343) was from Patara on the Aegean Sea and died as bishop of the nearby city of Myra; in 1087, most of his remains were surreptitiously moved to Bari, Italy, on the Adriatic. No sleigh-ride-in-the-snow opportunities in any of those places. He’s also the patron saint of toymakers, brewers, pawnbrokers, and unmarried people, among them those dang, fabled spinster cat owners. The Lorenzetti brothers probably worked on Maestà under Duccio’s direction and probably learned a thing or two about storytelling there, though Ambrogio’s got to be the champion of them all.

The narrative Nicholas paintings in the show are a pair of two-tiered and attached panels. Each pair would have flanked a central imaginary of the saint, now lost. One pair shows scenes from Nicholas’s youth. The other depicts miracles after his death. In one painting, Nicholas, from a rich family, slips a bag of coins through the window of the home of three young women whose father’s business failures cost them their dowries. Their father has just told them he plans to sell them into prostitution. The women are in extreme distress. It’s an indoor/outdoor scene — hard to do — but Ambrogio is good with architecture. Below is a split screen. In the foreground, Nicholas is told he’s going to be a bishop. The background is his consecration before an impressive Gothic altar, his back to us.

The other panel shows the saint’s spirit resuscitating a dead boy strangled by the Devil. The child had caught him doing devilish things. His father, finding him dead, had convened a group of Nicholas groupies, not elves, to pray for his intervention.

Below, in Saint Nicholas and the Grain Ships, the saint persuades the captain of a fleet loaded with grain bound from Egypt to Rome to dock at famine-stricken Myra and to leave enough grain to feed the city. The captain resists, since the grain was carefully measured. Nicholas gives him a “be good for goodness’ sake” talk, and he relents. Ambrogio paints two ships so emptied of grain that they rise high from the water. Another ship, having left port also emptied, is so miraculously replenished that it barely hovers above the waterline.

All convoluted stories, to be sure, but Ambrogio was hired to draw from The Golden Legend, published just at the end of the 1200s and the definitive catalogue of saintly capers. He was able to take the weirdest stories, including “Saint Nicholas and the Grain Ships,” and convey them efficiently.

I enjoyed the section on the sculptor Tino di Camaino (c. 1280–c.1337) since I knew nothing about him. When sculptors in, say, Florence or Siena wanted to do something new, they had centuries of sculpture, going back to antiquity, to plump. Early Italian painters weren’t so blessed. By the 1320s, though, Tino could look at Duccio, the Lorenzettis, and Martini, for inspiration.

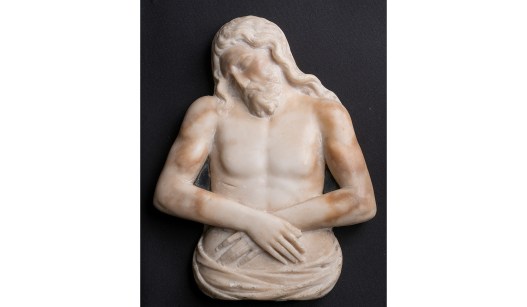

His Man of Sorrows, from around 1330, isn’t something to be found in French ivories, which, for all their plasticity and drapery, are very busy beehives. It’s got pathos. There’s no blood and gore. Jesus looks asleep, muscles relaxed, fingers poised, his head inclined and hair draping his shoulders. The Pisano sculptors, father Nicola and son Giovanni, were already making figures with defined muscles, ligaments, and tendons, heading toward the Renaissance. Tino’s Jesus isn’t a cartoon figure. He’s real, but in Gothic spirit, there but not there.

Martini was, we learn, a pioneer of the International Gothic painting style. Suave, sometimes flamboyant, and high-keyed, it’s considered a courtly, or aristocratic, style, decorative, French, and what I’d call Gothic Mannerism. It comes before Renaissance classicism — think Masaccio — if we’re parsing art into movements. Lorenzo Monaco, the Limbourg brothers, and Gentile da Fabriano are the kingfish in the movement, which reached its peak in the 1420s, long after Martini died.

Rise of Painting ends with Martini and the International Gothic style, and, alas, it’s a sputter. A Bohemian Virgin and Child Enthroned from the late 1340s is a clunker. There’s a sheet from The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry, by the Limbourg brothers, from between 1405 and 1409. An essay in the catalogue compares The Belles Heures and Simone’s Orsini Polyptych, and does it well with lots of dynamic, spot-on illustrations. The gallery in the exhibition, though, is a disjointed fizzle, as if the curators were exhausted from all the loan negotiations. I wouldn’t blame them, but I like splashy exhibition endings.

One of the virtues of The Rise of Painting is that it kindles the itch to go to Siena. Most of Duccio’s Maestà is there, and it has to be seen to be believed. Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s Allegory of Good and Bad Government, from 1338–39, is a showstopper, but it’s a fresco and can’t be moved. The Good Government panels are filled with scenes of peace, justice, wisdom, and fortitude — nice — and though the players in Bad Government get coal in their stockings, their brand of naughty is engrossing. Horns, fangs, critters you wouldn’t pet if you like your arms, and passages of deceit, fraud, cruelty, and devastation abound.

What about architecture? Siena’s cathedral, or duomo, defines the city more than anything, and it ain’t goin’ anywhere. It has a million parts and took most of the 1200s to build, but its dazzling, polychrome marble and mosaic façade, stained glass, and sculpture are all from the end of the century or the first few years of the 1300s. The inlaid marble mosaic floors are the supreme flower of terra firma — nearly 60 depictions of divinities framed by rectangles, hexagons, and rhombuses in black, white, red, and green. They were restored around ten years ago. They’re mostly from the 15th and 16th centuries, and covered most of the year except in September.

The Piccolomini Library frescoes by Pinturicchio are in the cathedral, too. The Black Death devastated Siena, but the city surged — briefly — during the papacy of Pius II, who was once Siena’s archbishop. The frescos celebrate Pius — a Piccolomini — and were painted between 1503 and 1508. They’re among Europe’s most dazzling and least-known art experiences. Saint Catherine of Siena’s mummified, severed head, also in the cathedral, rivets more than dazzles. She was a Sienese mystic nun who died in 1380.

Siena’s allure never ends. Catherine became the patron saint of Italy, a primo appointment if there ever was one. And she was dead after her body was dismembered for relics.

And Siena’s big, clamshell-shaped piazza is one of Italy’s most elegant. I saw the Pet Shop Boys there in the mid ’80s when they performed on Italy’s version of Solid Gold, filmed in the piazza. Italians love pulsing, colored confetti lights and are smooth, natural flirts in a nighttime crowd, let me tell you.

I’d rather crawl over hot molten glass than go to the Palio, a twice-a-summer mob scene all day and a horse race that’s over in a minute. Each cantado, or neighborhood, fields a parade team. I was once in Siena a week before the race and saw the rehearsals, which were fun, taken very seriously by the locals, and the soupçon of the Palio I wanted.

Rise of Painting’s catalogue is first-rate. It’s edited by Joanna Cannon, a retired professor at the Courtauld Institute of Art, with Caroline Campbell, the director of the National Gallery in Dublin, and Stephan Wolohojian, a curator at the Met. It’s great, new scholarship grounded in how the art would have been experienced by viewers. Big subjects — Duccio’s Maestà, Sienese goldsmiths, and profiles of the key artists — are mixed with focused essays on individual objects. It’s beautifully written and illustrated. The exhibition travels to the National Gallery in London as one of its 200th-anniversary shows. I wouldn’t have missed it. And you shouldn’t, either.

If there is an interest in seeing the previous articles referenced, I would be happy to post them.