The American Revolution…

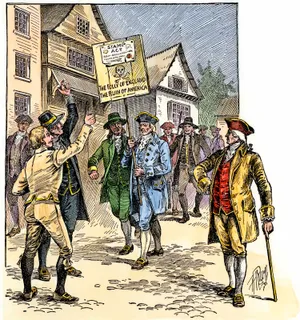

Featured image: Procession in New York opposing the Stamp Act, depicted in a hand-colored woodcut.

How it all began… Part 3

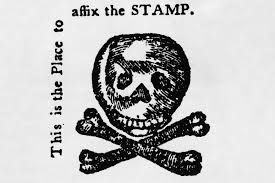

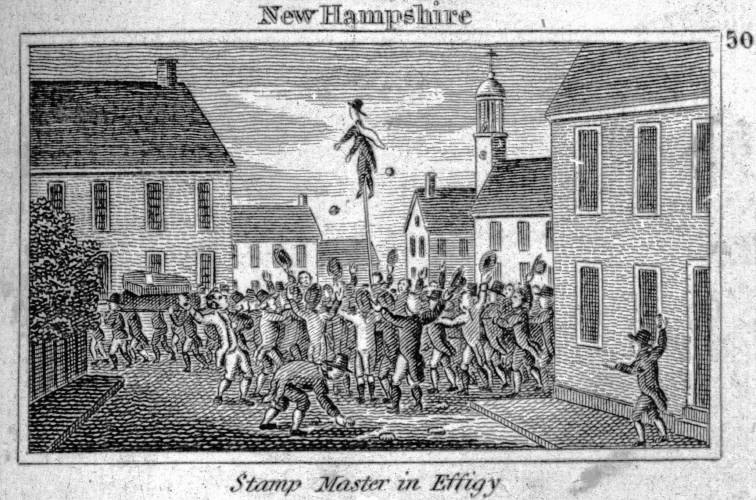

The furor raised by the Stamp Act was almost universal in the colonies. The Stamp Act was designed and implemented by Minister George Glenville. While the Trade and Navigation Acts affected the more affluent people, the Stamp Act in effect reached all levels of the colonial society.

This was never more evident than the reaction to the passage Patrick Henry’s “Virginia Resolves”, May 29, 1765. Virginia governor Fauquier decided not to recall the House of Burgesses for fear that to do so would add fuel to an already turbulent situation even though the Burgesses only passed 4 of Henry’s 7 resolves.

Newspapers of the time printed all 7 resolves as if the entire body of resolves were passed by the House of Burgesses. This resulted in many calling the resolves treason as did James Otis of Massachusetts, Alexander McDougall and John Morin Scott of New York. Scott would later become one of the most radical of the “Sons of Liberty”.

Many colonial citizens found themselves in accord with the resolves as they expressed the feelings of many colonials but were afraid to voice their opinion. While the Trade and Navigation Acts did not solidify colonial opposition, the Stamp Act galvanized the feelings of most colonials. Instead of driving a wedge between the more affluent colonials and the more common man, the Stamp Act gave them a reason to stand united in opposition to the heavy handed actions of the English Parliament.

Colonial opposition boiled over and spread terror among the Officers of the Crown and their Stamp Agents to the effect that most of the Stamp Agents renounced their commission to avoid being targeted by the colonial citizenry. This was not a plebian reaction, but one that was supported and directed by many of the more wealthy men of the colonies. (Plebian; the common people)

James Otis swore that the two main architects of the Stamp Act were Massachusetts’ own Thomas Hutchison and Andrew Oliver, two of the most prominent men in Massachusetts. Benjamin Franklin tried without success to foil the passage of the Stamp Act, but was resigned to its passage. Franklin’s friend John Hughes was appointed a Stamp Agent at Franklin’s request, but was later forced to resign his commission. This did little to enhance Franklin’s popularity in Pennsylvania but he was eventually forgiven for his actions after his return to America.

James Otis proposed a Stamp Act Congress be held in New York in October, 1765 to solidify colonial opposition to the Stamp Act. Conservative infighting would doom the congress to inactivity and several of the delegates would later lose their seat in the colonial legislative bodies. After the demise of the Stamp Act Congress, Otis would beg Americans to stop rioting and petition Parliament and the Crown to stop before America fell into “painful Scenes of Tumult, Confusion and Distress”.

There is little reason to doubt, had Great Britain tried to use force to impose the Stamp Act, as Ben Franklin said, “a British Army would not have found a rebellion in the American colonies in 1765 but it would have made one.” Resistance to the Stamp Act was so strong that some patriots declared they would “fight up to their knees in blood” if Britain tried to force imposition of the hated act.

The weakness of British forces in America at the time forced the British to decline to act against the fury of the American colonies. Many conservatives asked that Parliament be given the time and opportunity to repeal the act in order to fend off the possibility of armed resistance to British Troops trying to force adoption of the Stamp Act.

In order to blunt the Stamp Act, Americans began to boycott English products; coupled with the riots the act prompted many in England to conclude that a full-blown rebellion was under way in the colonies. This would force many English merchants to fear a collapse of the British economy; it was this fear that set the much of the merchant class to support the repeal of the Stamp Act.

Not all Britons favored repealing the act, among the most violently opposed was the Bedford Party, also known as the “Bloomsbury Gang”. They favored using arms against the Americans in order to force the colonials to accept the act. They suggested that all charters of the colonies be abolished, force the colonial assemblies to be replaced with more amenable colonial citizens and spill the blood of the more rebellious in order that the colonies accept ALL acts by Parliament. In the eyes of the Bedford’s, to butcher all Americans that did not bow down to the English Parliament was the most expedient way to end the controversy.

The replacement of Minister George Grenville by the Marquis of Rockingham (Charles Watson-Wentworth) in July, 1765 set the stage for Rockingham’s ministry to begin the repeal of the Stamp Act. A series of strongly worded petitions began to flood Parliament as the merchant class began to see the effects of the Stamp Act as a major loss of trade in the American colonies. The layoff of many workers in the English factories began to spell a danger to the peace and tranquility of the manufacturing centers of England. The merchants claimed repeal of the Stamp Act was needed to bring prosperity back to England.

The Stamp Act was officially repealed March 18, 1766 and the Declaratory Act was enacted as part of the repeal. The Declaratory Act stated that Parliament’s authority was the same in Britain as well as the American colonies; that Parliament’s authority to pass legislation was as binding in America as it was in Britain. In the colonies, James Otis, Samuel Adams and Patrick Henry saw the act as a way to deny colonial rights of “NO Taxation Without Representation”. Although the Declaratory Act passed the English Parliament, no bill of taxation against the American colonies ever came to pass.