The Battle of New Orleans

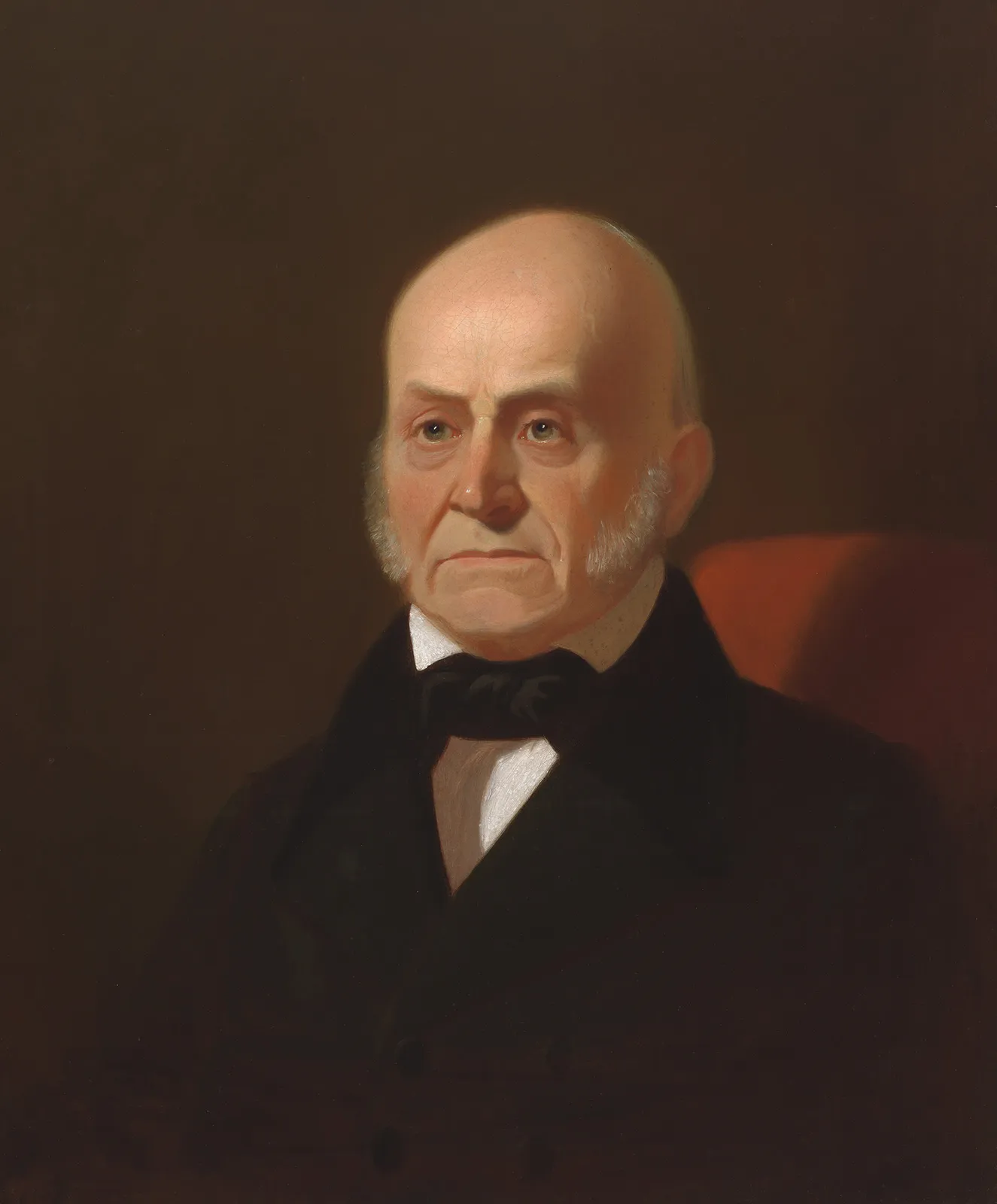

Andrew Jackson leading US forces at the Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans encompassed a number of actions beginning in 1814 culminating in January 1815. We will examine these actions and some of the individuals involved.

The War of 1812 began as a result of British interference with US trade and the impressment of US citizens. A declaration of war would pit the fledgling US against the world’s premier military. The British fielded a Navy that dominated the seas and an Army that could contend with Napoleon. The declaration set in motion a series of events that would forever change history. It is the culmination of this war and the events that preceded it that we will examine.

A series of devastating defeats plagued the Americans in the early months of the war but a naval victory on Lake Erie September 10, 1813 by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry followed by a bloodied but victorious Army at Lundy’s Lane July 25, 1814 temporarily stunned the British. Admiral Cochrane began his Chesapeake campaign that resulted in the disaster ever known as the Bladensburg Races and the burning of the capitol including the White House by Admiral Cockburn and General Ross August 24; the failure of Cochrane’s naval bombardment to defeat the forces at Ft. McHenry under the command of Major George Armistead and the death of General Robert Ross ended the Battle of Baltimore (September 12-15, 1814) and the end of Admiral Cochrane’s Chesapeake campaign.

On September 3, 1814 a British Naval envoy, Capt. Nicholas Lockyer visited Jean Lafitte at Barataria and offered emoluments to Lafitte and his men should they join his forces in capturing the city of New Orleans. Lafitte to his honor sent the message to American authorities, making it known that the city was the target of invasion. Lafitte offered to help in the defense of the city for the release of his brother Pierre, Dominique You, Renato Beluche and others of his associates being held on piracy charges.

September 3rd was also the date of Lt. General Sir George Prevost’s advance down the west coast of Lake Champlain in an attempt to gain as much American territory as possible before any treaty was ratified to end the war. Control of Lake Champlain was vital as a supply line, but a plucky US Navy Lt. by the name of Thomas Macdonough defeated the British naval force under the command of Captain George Downey at Plattsburg on September 11, 1814 forcing the British to return to their bases in Canada.

The British secret campaign (that turned out to not be so secret) to wrest New Orleans from the Americans, to close the Mississippi, drive all settlers back across the Appalachian chain and return the lands from the crest of the Appalachians to the Mississippi to the Indian tribes was about to unravel. The brainchild of Lord Robert Castlereagh, it would include an end to fishing rights on the Grand Banks, allow no US Naval forces on the Great Lakes and a surrender of much of the Louisiana Purchase; to be conducted under an “Uti Possidentis” claim to retain all lands and territories under their command at the end of hostilities.

The massacre at Fort Mims August 30, 1813, would bring “Andy” Jackson and his Army into the fray and with the defeat of the Creek Nation at Horse Shoe Bend March 27, 1814 would thwart the British effort to bring several Native American Tribes to an alliance with British forces. Further restricting the aims of the British would be Jackson’s capture of Mobile September 13, 1814 and Pensacola November 7, 1814 barring an overland route to New Orleans. These three actions severely reduced Jackson’s supply of powder and flints for rifles as well as ammunition for his artillery.

Major General Andrew Jackson arrived in the city of New Orleans December 1, 1814 to find a city in near panic and disarray. He was met By Edward Livingston, an old friend from Jackson’s days in the congress. As head of the committee for the defense of New Orleans, Livingston was indispensable as an unofficial aide de camp to Jackson, was his channel to Governor Claiborne and was instrumental in arranging a meeting between Jackson and Jean Lafitte. Initially Jackson bristled at the suggestion that he deal with Lafitte whom he called a pirate.

Included in Jackson’s staff was Major Arsene Lacarriere Latour, a former French military engineer with extensive experience and superb map-making skills. Together they toured the possible avenues of attack, made troop assignments and decided where to build fortifications. When Major Howell Tatum queried about a water table that precluded the digging of trenches and the construction of defenses, the doughty little major replied, “with engineering ingenuity my dear major”.

The sea lakes that border New Orleans were the obvious choice to facilitate an attack on the city. Commodore Daniel Patterson ordered a small armada of gun boats to defend the lakes. Jackson placed the Mississippi Dragoons (a cavalry troop that fought as infantrymen) under Major Thomas Hinds and a contingent of Choctaw warriors under Pierre Juzan to be the eyes and ears on the Plain of Gentilly, a route that could afford the British a level field with little to no obstructions. This was in Jackson’s words “the front door” and asked Latour if there was a “back door”.

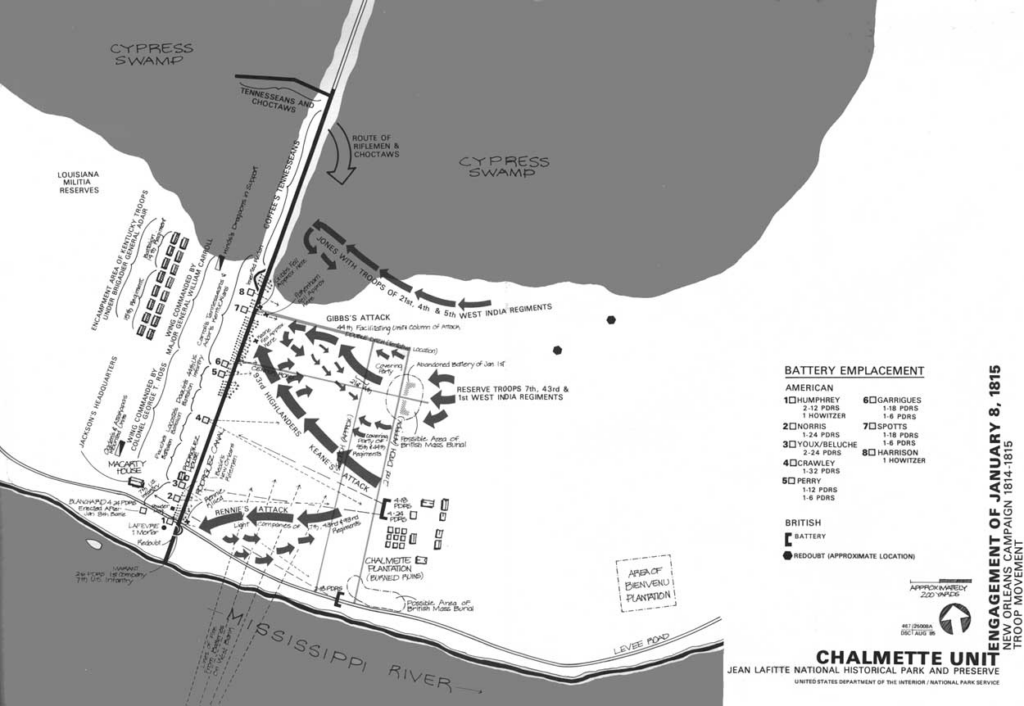

The ‘back door’ as Major Latour defined it was a narrow stretch of land approximately 800 yards wide with the Mississippi River on one side and cypress swamps on the east side. The land was cut with drainage canals that allowed flood water to be drained from the fields into the bayous. It was these bayous with their connection to Lake Borgne that concerned Jackson and he ordered that they be closed by falling cypress trees into the bayous.

Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane arrived off the Louisiana coast December 9, 1814 with 60 British ships and nearly 14,500 sailors and soldiers. The invasion plans called for the forces to be landed on an island in Lake Borgne. Blocking entry into Lake Borgne was a small flotilla of gun boats under the command of Lt. Thomas Jones, US Navy.

The British pitted over 40 long boats outfitted with small cannon, the attendant crew and 40 sailors or marines per boat as oarsmen and boarders against Lt. Jones and his becalmed boats. Unable to maneuver, outnumbered, outgunned and wounded in the battle that ensued, Lt. Jones’ small American force surrendered on December 14 to the British leaving open the entry to Lake Borgne and Jackson with no eyes on the British fleet.

Loss of eyes on the Lakes forced Jackson to reconsider Lafitte’s offer of ammunition and flints in exchange for pardons for his men. In the ensuing agreement Jean Lafitte would return to Barataria to be Jackson’s eyes on the Gulf; Pierre, Jean’s older brother was released and became Jackson’s aide because of his extensive knowledge of the area and possibly as a guarantee against treachery. Recognized for their gunnery skills and appointed captains, Dominique You and Renato Beluche commanded and organized artillery units manned by the released Baratarians.

General Keane established a garrison on Pea Island and began to explore the cypress swamps for any avenue to advance closer to the city. British scouts discovered that Bayou Bienvenu was not blocked as the other bayous had been.

Near the bayous entry into Lake Borgne was a small village of Spanish fisherman. Bribed by the British, one of the fishermen guided the British to the camp of a small detachment of Louisiana militia. Without firing a shot the British captured the small detachment including Major Gabriel Villere. The canal that drained the Villere Plantation drained first into Bayou Mazant then connected with Bayou Bienvenu.

The British led by the fisherman arrived on the east bank of the Mississippi taking command of the Villere Plantation. General Keane established a camp only 9 miles south of the city with some 1,800 British troops on the morning of December 23rd. Later that day an escaped and embarrassed Major Villere reported to General Jackson; informed of the British encroachment, an angry Jackson is said to have exclaimed, “By the Eternal, they shall not sleep on our soil” and promptly gathered forces to attack the British Camp.

In a surprise attack that evening (called the Fight in the Dark) the Americans would forestall any further advance by the British. General Keane, somewhat unnerved by the ferocity of the attack made the fateful decision to await reinforcements before advancing. It can be argued that Jackson’s decision to attack Keane’s forces and the resulting delays may have saved the city and doomed the British.

As the British settled in on that first evening, the USS Carolina began shelling the camp just as General Jack Coffee’s Tennesseans attacked the opposite side of the camp. “The Battle in the Dark” was under way. After the initial shock the British were able to recover, the battle became a bitter hand to hand affair. Unable to rout and drive his enemy away; Jackson pulled his troops back behind the Rodriguez Canal to await the eventual British advance.

Ongoing harassment by Jackson’s sharpshooters and stealthy raids by the Choctaw warriors would keep the British Camp in turmoil. General Pakenham would complain in a letter to Jackson that killing his sentries in the dark was ungentlemanly to which Jackson replied that they would use all means necessary against the invaders. The British would be harassed and hampered until they vacated all troops from Louisiana on January 18, 1815.

Part of the attack on the British camp was carried out by the USS Carolina and for three days and nights continued to harass and bombard the British camp. Unbeknownst to the Captain of the Carolina, heavy guns from the fleet arrived in General Keane’s camp December 26, the next morning, the 27th; British gunners repeatedly hit the schooner with heated shot. The big guns out ranged the smaller guns of the Carolina. The heated shot started numerous small fires that quickly spread. Unable to subdue the fires the ship was ordered abandoned; when the fires reached the magazine, the USS Carolina blew up.

The “engineering ingenuity” of Major Latour oversaw the transformation of the Rodriguez Canal from a simple drainage canal to a fortified position known as “The Jackson Line” while the British sought to bolster its forces. Composed of soil and mud with a log facing, the line gave protection to Jackson’s troops while presenting an obstacle of the drainage canal of up to 8 feet deep and 15 feet wide showcased Major Latour’s sample of “engineering ingenuity”. Artillery was spaced along the line, tasked with silencing the British guns and to ravage the British infantry with shot, shell and grape shot.

On December 28, Major General Sir Edward Pakenham ordered a ”Grand Reconnaissance”, The indecision when confronted with the canal and its unknown depth would bring the British to pause. The withering fire from the line and the cannon began to take a toll. Pakenham called off the affair and the British withdrew. Had they persevered in the advance in the cypress swamp, they would have turned Jackson’s flank when the militia withdrew from their positions. An angry General Jackson would replace the militia with General William Carroll’s Kentucky and General Jack Coffee’s Tennessee troops, and place more cannon on the line.

Pakenham was not satisfied with the position his army had been placed in and wanted to change the plan of attack. As a result he would clash with Admiral Cochrane but an outranked Pakenham would have to fight on the ground they now held. Cochrane knew of the efforts to produce a treaty with its “Uti Possidentis” clause and felt that time was of the essence. The die was cast, Pakenham would play the hand he was dealt.

General Pakenham and his staff planned a three prong attack utilizing nearly 5,500 men and a reserve of about 4,500. A force of 1,400 under Colonel Thornton would cross the river and attack the gun emplacements of Commodore Patterson across from Jackson’s main position. Meanwhile General Keane would strike the end of the line next to the river and General Gibbs would skirt the cypress swamp and attack what appeared to be a lower, thus vulnerable part of the line. A Creole deserter by the name of Galvez told the British that particular segment of the line was manned by militia. Convinced that the American militia could be routed and then flank the guns, the British were confident of success.

A series of blunders plagued the British on that fateful day, January 8, 1815. General Jackson was awakened at 1:00 AM with a request for additional manpower from the militia commander General Morgan across the river. Convinced that the attack was coming on his side of the river, he refused the request, roused his staff and awaited the British. General Morgan began to align his 800 men to help defend Commodore Patterson’s guns. By 4:00 AM General Adair moved his Kentucky militia to within 50 yards of the line as reinforcement.

For starters the canal was too shallow to float the heavily laden boats, dragged through the mud and way behind schedule, plus a lack of boats forced Thornton to go with just 500 men; a strong current carried his force 1,000 yards further downstream than planned. Although successful in routing the militia defending the guns with 300 men but lacking the manpower necessary to carry out the main objective of turning the guns on the “Jackson Line”; Thornton pulled his men back to a position of safety to await the rest of his men. They attacked the Commodore’s sailors and marines manning the batteries. Seeing they were to be over-run, General Morgan and Commodore Patterson spiked their guns and pulled back.

Thornton had accomplished his mission but it had little effect on the outcome as the battle on Jackson’s side of the river was ending.

In a predawn fog, the British General Pakenham began to marshal his forces. Hearing no sounds of engagement from Thornton’s force across the river and Patterson’s guns raking General Keane’s troops; Pakenham ordered a change. Instead of General Keane following up Colonel Robert Rennie’s attack on the line, he was to move his force to join that of General Gibbs. As a consequence, Colonel Rennie’s initial success went unsupported and was thrown back.

Visibility improved as the fog lifted, the American guns began to thunder when the British were at 600 yards. Disaster strikes when Lt, Colonel Thomas Mullins, charged with bringing the ladders and fascines to facilitate crossing the canal and climbing the parapet, forgets the location and marches his man past where they were stored. He sent 300 of his men back to retrieve the needed articles, only a few actually made it back to the canal in the ensuing confusion. As the British push forward, at 400 yards some of the marksmen from Kentucky and Tennessee militia units begin to take down officers and sergeants. At 300 yards many more began to shoot, relays of men on the firing line; fire, fall back and reload, 4 men in each relay taking careful aim at the advancing British.

The cannon charged with grape shot tore huge swaths through the columns of British infantry and the aimed rifle fire began to take its toll as the leaderless and confused troops faltered at the canal. Unable to advance, they were at the mercy of the rifles and the cannon. General Keane was wounded in the move to support General Gibbs.

The troops bringing up the fascines and ladders faltered and many never made it to the front. Gibbs and Pakenham were both killed by grapeshot. The aimed rifle fire and the anti-personnel loads of grape shot from the cannon decimated the British troops. At that point General Lambert assumed command and ordered his reserve troops to support a withdrawal of the Army from the field.

When the firing stopped the carnage became visible, the ground carpeted in the red of British uniforms. In a time span of 25 minutes, the British dream of “Uti Possidentis” and control of the American continent came crashing down in a sea of red. General Jackson’s initial report put the British losses at 700 killed, 1400 wounded and 500 captured for a total of 2600 men; these numbers would be corrected later.

The British side of the ledger looked bad and would only get worse. The Creole deserter Galvez would be hung by the British, they thought him a spy.

An angry Admiral Cochrane, still determined to take the city of New Orleans began to assault Ft. St. Philip guarding the mouth of the Mississippi January 9; ten days of bombardment convinced Cochrane that his efforts were futile and withdrew January 18.

General Lambert held a council of war with his officers and decided that the cost of capturing New Orleans was too costly with the chance of total defeat should they try. By January 19 the British camp on the Villere Plantation was evacuated and the fleet set sail for Mobile Bay February 4, 1815.

February 12th the British attacked and captured Fort Bowyer at the mouth of Mobile Bay. News of the Treaty of Ghent arrived the next day; the treaty called for the return of military gains to each other. Shortly thereafter the British abandoned Fort Bowyer and set sail for their base in Jamaica.

British casualties for the campaign, 386 killed, 1,521 wounded and 552 missing or captured for a total of 2,459.

Lt. Col. Mullins would face excoriation and reprimand for his failure to fulfill his task by having the fascines and ladders to the front in a timely manner.

General Pakenham had secret orders that he was not to stop military actions against the American’s until he received verification that the American President had signed the treaty. Had Pakenham been successful in capturing New Orleans the British government was willing to refute the terms of the Treaty of Ghent and impose the harsh conditions advocated by Lord Castlereagh under a claim of “Uti Possidentis”.

The American ledger by contrast looked bright; General Jackson would recognize the meritorious action of several, including Major Latour, Colonel Hinds and his “Troop of Horse”, the Lafitte brothers, Captains You and Beluche among others. Major Villere faced severe charges for his failure to follow orders, but his action in the battle made up for his shortcomings. In February of 1815, President James Madison signed pardons for the Baratarians.

The war would force the US government to the realization that the need for a standing army was just as necessary as a strong navy. James Monroe would continue these policies.