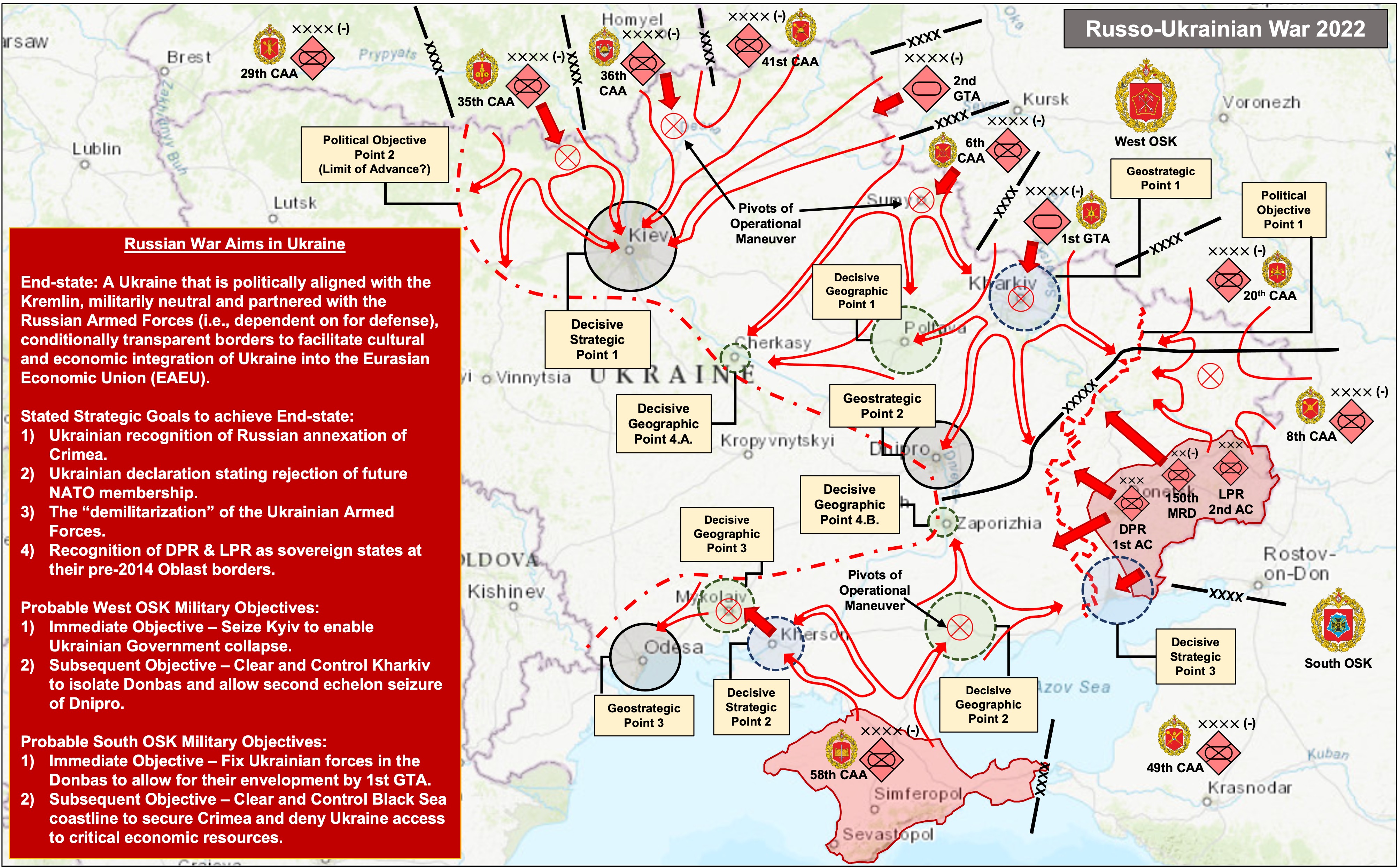

The Russian-Ukrainian War, Part V

If We’re Gonna Lose…Can We Lose in August?

In 1994 the Yeltsin government believed that fighting and winning the war in Chechnya was necessary for their political survival. That defeat in Chechnya would doom them in the next election or result in a coup before the 1996 ever arrived. They were probably right, but the political death came much slower than anyone expected.

Faced with a deeply unpopular war and extreme economic challenges, Yeltsin and his advisors knew they had severe political headwinds to over come. That the war which was lost in all but the declaration, had not been declared lost yet. There was a narrow path to political survival if they acted with extreme care.

The Yeltsin campaign came out early and broke nearly every election law in the book in its efforts to remain in power. Yeltsin signed a decree in 1996 to abolish conscription in Russia by the year 2000, and create an all-volunteer, professional force without consulting with his discredited Minister of Defence Pavel Grachev. This gave Russian mothers and fathers the prospect of a future where their sons would not be involuntarily committed to disastrous and unpopular wars which certainly helped Yetlsin while his principle opponents in 1996 offered only the same involuntary military service that was terribly unpopular.

The Clinton Administration pulled every lever of American soft power at its disposal to prop up Yeltsin. Yeltsin was also assisted by politically weak opponents, except perhaps Alexander Lebed whose popularity grew immediately with more national exposure in 1996 election. The fact the Chechen war was not lost before June 16, 1996 the date the first round of the presidential election or by July 3, 1996 the date for the second round of the presidential election, was probably single most important factor that determined Yeltsin remained in power. In Yeltsin’s runoff with the weak, “lets return to communism” candidate Gennady Zyuganov, Yeltsin won only 54.4% of the vote.

The First Chechen War was officially lost on August 31, 1996 exactly 59 days after Yeltsin won the 2nd round runoff.

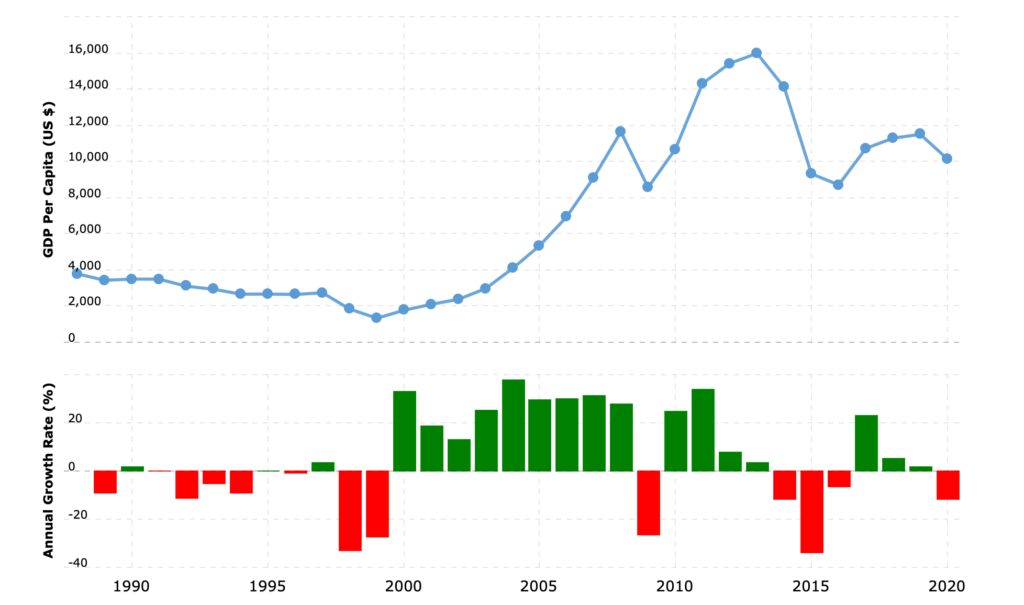

Economic fallout…Solutions Will Come Too Late..

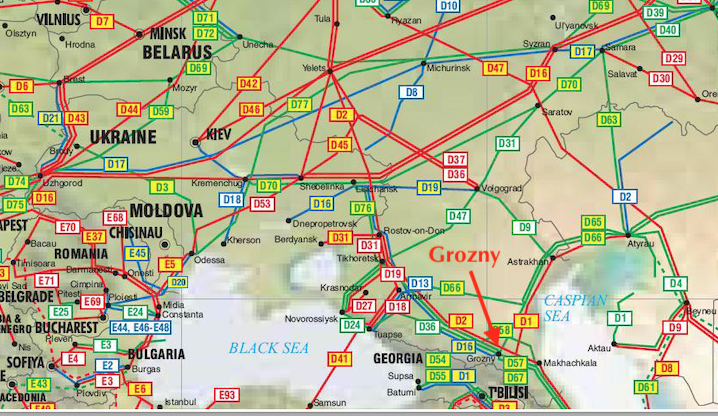

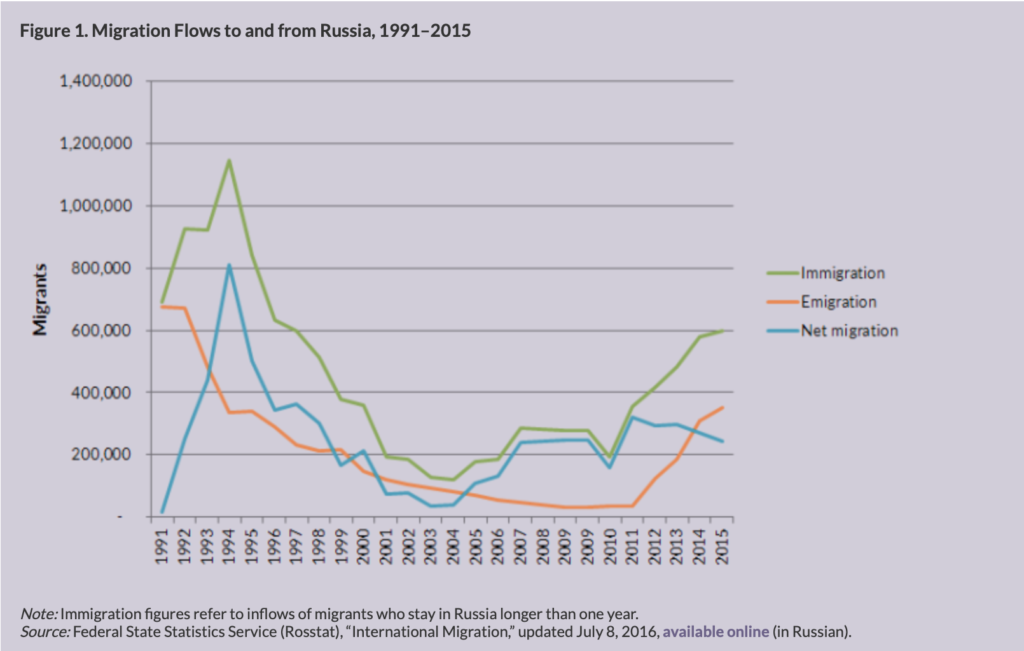

The Yeltsin administration began immediate plans for building a pipeline around Chechnya through Dagestan so so they could get oil export flowing independent of what might happen in Chechnya. This Chechenya- bypass loop project would not be complete before Yeltsin presidency was ended and a new war in Chechnya was started by a new Russian president promising vengeance for Russian honor and the Russian dead…a political unknown at the time…one Vladimir Putin. In the meantime, Russia had to pay confiscatory transit fees for the oil in the pipelines it built to the enemy it just fought and lost as war to. These transit fees were paid in hard currency, that same hard currency Russia desperately needed to stabilize and modernize its economy. As unwelcome as paying transit fees where to Russia, it was the inability of an independent Chechnya to protect the pipeline that hurt revenue most significantly. Guerrillas with no opportunities but further violence constantly disrupted the oil flow. Russia’s economy suffered.

Reform the Army…by Making a Mess of Reforming the Army Due to Palace Intrigue…

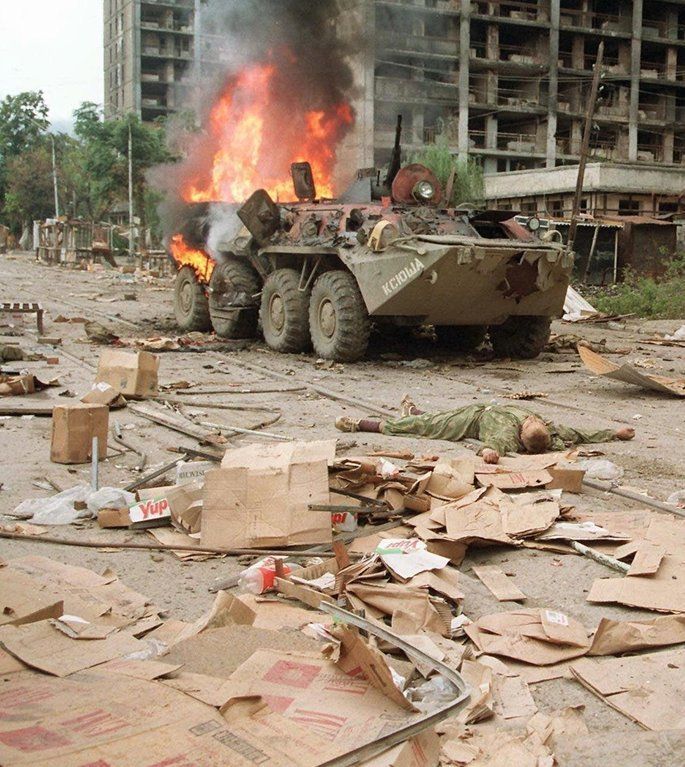

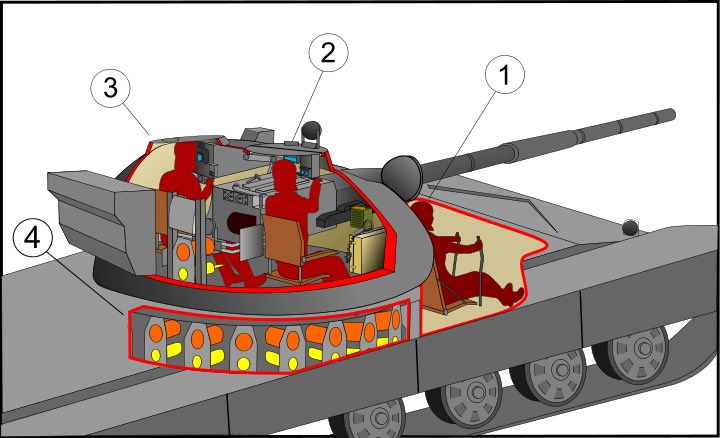

Two weeks after the presidential runoff election which secured Yeltsin’s victory, Yeltsin fired Defense Minister Pavel Grachev who was the primary architect of the First Chechen War. Prior to that, Grachev was involved in the Soviet coup attempt of 1991 yet managed to retain power as he transitioned from the Soviet Union’s last Defense Minister to become the Russian Federation’s first defense Minister. Grachev was also involved in the Russian constitutional crisis of 1993 (Coup of 1993), where he sided with Yeltsin. As Russian armor and infantry were dying in the Dec 31, 1994 assault in Grozny that was meant capture the capital and win the war…in effect a “D-Day” and “Capture of Berlin” operation all rolled into one, Grachev was drunk all day celebrating his birthday.

Grachev had remarked recently that only an “incompetent commander” would order tanks into the streets of central Grozny, where they would be vulnerable to rocket launchers, grenades, even Molotov cocktails. Yet at the end of December he did it.

“Why It All Went So Very Wrong” by bruce W. Nelan

“In Yeltsin’s address to Parliament in February, 1995, he admitted that “reforms in the armed forces have not proceeded satisfactorily” and promised that he would take decisive measures in 1995 to reorganize the army and other forces. On February 23, 1995, after a wreath-laying ceremony at the tomb of the unknown soldier, Yeltsin said “the army has begun to fall to pieces,” precisely because “we have been late in introducing reforms.”

A year passed and nothing happened. In February, 1996, after a meeting of the Russian Security Council, it was announced that Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin must put forward a plan for military reform within ten days. When I called the Defense Ministry to find out whether they were working around the clock to accomplish this on time, the officers there replied that they had heard the announcement, but that Grachev had gone to ex-Yugoslavia, his first deputy Andrei Kokoshin had a cold, and if Chernomyrdin was charged with reforming the army in ten days, that was his problem.

Clearly, the military had long since stopped taking Yeltsin’s “imminent army reform” pronouncements seriously.” – Pavel Felgenhauer, RUSSIAN MILITARY REFORM: TEN YEARS OF FAILURE

The next Minister of Defence of the Russian Federation was placeholder, Mikhail Kolesnikov. Kolesnikov who was appointed acting Minister of Defence of the Russian Federation. Kolesnikov could make none of the institutional changes of the army that were required as everyone knew his position was temporary. As such, Kolesnikov appointment as acting Minister of Defence further reflects the disarray of the Yeltsin Administration at the time and characteristic of Russia’s inability to make the necessary changes to modernize and reform the army.

The next Minister of Defence of the Russian Federation was Igor Rodionov who was selected as much for his his political reliability as for his declared willingness to reform the armed forces. Rodionov proved to be perhaps the worst possible choice as Minister of Defense. Instead of advocating reform of the Russian military, Rodionov came to the conclusion that it was Russian society that needed be reformed in order to support the Russian army’s needs as constituted. The army “tail” was to wag society’s “dog”.

“It is … impermissible to solve society’s … problems at the cost of lowering the state’s main attribute, the army”

Igor Rodionov,

Manoeuvring with the Military, 1997

An important reform proposed by Rodionov was the specific call for the creation of a professional NCO corps in the Armed Forces. This NCO reform was critically important for the Russian army where the lack of a professional Russian Army NCO corps is seen as one of its greatest weaknesses relative to western armies. As of April 2022 in its Ukrainian War, the Russian Army still does not have a professional NCO corps.

Rodionov’s advocation of a “back to the future” soviet model for the Russian military was politically and economically impossible and doomed any positive reforms he advocated. In May 1997 Rodionov was fired. The Russian Federation had now three Ministers of Defence in less than a year at a time when the Russian military desperately needed reform. The Russian army, most desperate in need of reform, was just as broken as it was when any of the three assumed the office and it was about to get worse for the army in particular.

The next Minister of Defence of the Russian Federation was Igor Sergeyev. Sergeyev was appointed Minister of Defense in May of 1997. Unlike his predecessor, Sergeyev accepted that reform of the military must fit within the limited budget offered by civilian political leadership. Because of his conformance to the political and economic realties of the time, Sergeyev promoted to Marshal of the Russian Federation on November 21, 1997. Sergeyev to this day (April 10, 2022) remains the only Russian military officer to achieve the rank of Marshal of the Russian Federation.

Sergeyev spent nearly all of his career in the Strategic Rocket Forces and it was here that Sergeyev focused the lion share of funding and readiness. The Russian Space Forces were disbanded and absorbed into the Strategic Rocket Forces. Strategic Rocket Forces where to be the bulwark of Russian military powers they represented the biggest “bang for the buck”.

In December 1997, Sergeyev made the bold move of abolishing Russian Ground Forces Headquarters. In the words of Russian military expert, Michael Orr, the disbandment was a “military nonsense..justifiable only in terms of internal politics within the Ministry of Defence”. This was a severe blow, not just to the funding of the Russian army, but to the moral of the entire Russian Army. Suddenly…on the Russian Military organizational chart, the Russian Army was a subordinate force to the Russian Navy. Russian Air Force and Strategic Rocket Forces.

Authors Note: Disbandment of the Army seems incredibly shortsighted today, but it was not unique to Sergeyev. Similar thinking occurred in the US a decade earlier at the initial end of the Cold War as best represented in the December 11, 1989 article in the publication U.S. News & World Report entitled “Does America Need an Army?” This was an extremely wide read article that the US Army was taken very seriously as it is quoted in numbers publications at the time and since. In a nutshell, the article argues that with the Navy, Air Force and US Marines the USA has all the military power it needs. If the ground combat it too big a problem for the Marines, use strategic bombing…if that doesn’t work, nuke ’em. Fortunately for America, the buzz in political and military circles from this idea never gained traction real traction. Less than three years later the Gulf War would prove how valuable the US Army was with the US Army’s AirLand Battle doctrine which was the critical factor in the stunning victory with extremely low American losses that an “US Armly-less” military force could have never delivered

Yeltsin’s inadvertent savior from assassination in 1991, political rival and third place finisher in the 1996 election, VDV Afghan War hero, former commanding General of the 14th Guards Army in Transnistria Alexander Lebed became became Secretary of the Security Council in the Yeltsin administration on June 18, 1996. A deal was cut with Lebed when it became obvious that his late surge in the polls were not going to be enough to catupult him into second place. Lebed‘ support for Yeltsin was a factor in carrying a weak Yeltsin over the finish line in the 1996 election.

Lebed‘s first assignent was to negotiate an end to the First Chechen War which he accomplished in a few weeks. Lebed‘s ending of the First Chechen War brought him into direct conflict with Minister of Internal Affairs Army General Anatoly Kulikov and his faction who were responsible for running the war at that point. Lebed then clashed with the Yeltsin administration’s power broker and presidential chief of staff Anatoly Chubais. In the conflict with Chubais, Lebed was most guilty of simply being popular. Lebed was popular among Russian nationalists for how he handled the Transnistria situation. Lebed was popular among much of the military for his war hero status and command credentials. Lebed was popular among democrats for not-assassinating Yeltsin. Lebed was popular for being perceived as fair, honest and a man who got quickly results…three traits that seemed impossible to find in Russian post-Soviet politics. Lebed‘s popularity grew during the election and if the election season in Russia were a few weeks longer, he could have unseated a weak and fading Yeltsin. Lebed was seen by many as the next president of Russia and that was a problem for Chubais who intended to be president of Russia himself in 2000.

Lebed argued in the Yeltsin administration that Russian soldiers needed more pay and more support as they exited the military or they would revolt. Chubais accused Lebed of agitating the emotions of soldiers with the intent of inciting a coup. When push came to shove, Lebed had all ready accomplished the two things what was most useful to the Yeltsin administration. Lebed had help Yetlsin survive the 1996 runoff and he ended the war. On October 17, 1996, les than 5 months after assuming the position of Secretary of the Security Council Lebed was fired. The Russian soldiery lost their greatest advocate in government. Moral dropped even lower.

Authors Note: Lebed went on to be governor of the largest region in Russia despite being an outsider. Mysteriously Lebed chose not to run as for president in 2000 leaving Vladimir Putin unopposed as the “unlikely” incumbent in the 2000 election. Always considered a threat to Putin, Lebed died in a helicopter crash in 2002 that is considered by some to be suspicious.. Lebed‘s story is a fascinating one which deserves more detail than can be provided in this series.

The Bitter Pill Sticks in the Throat…

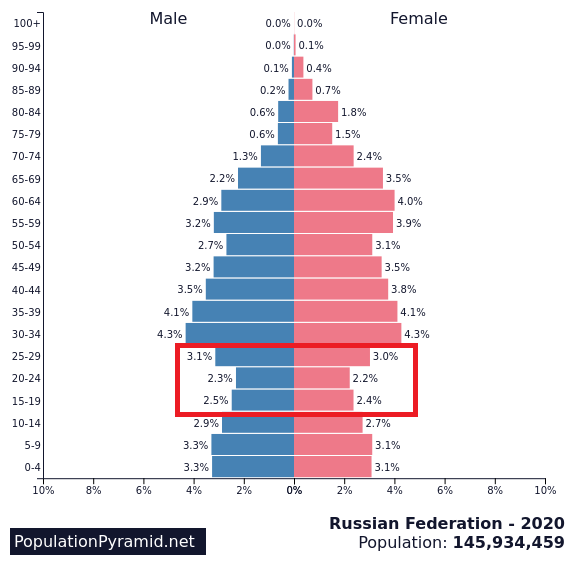

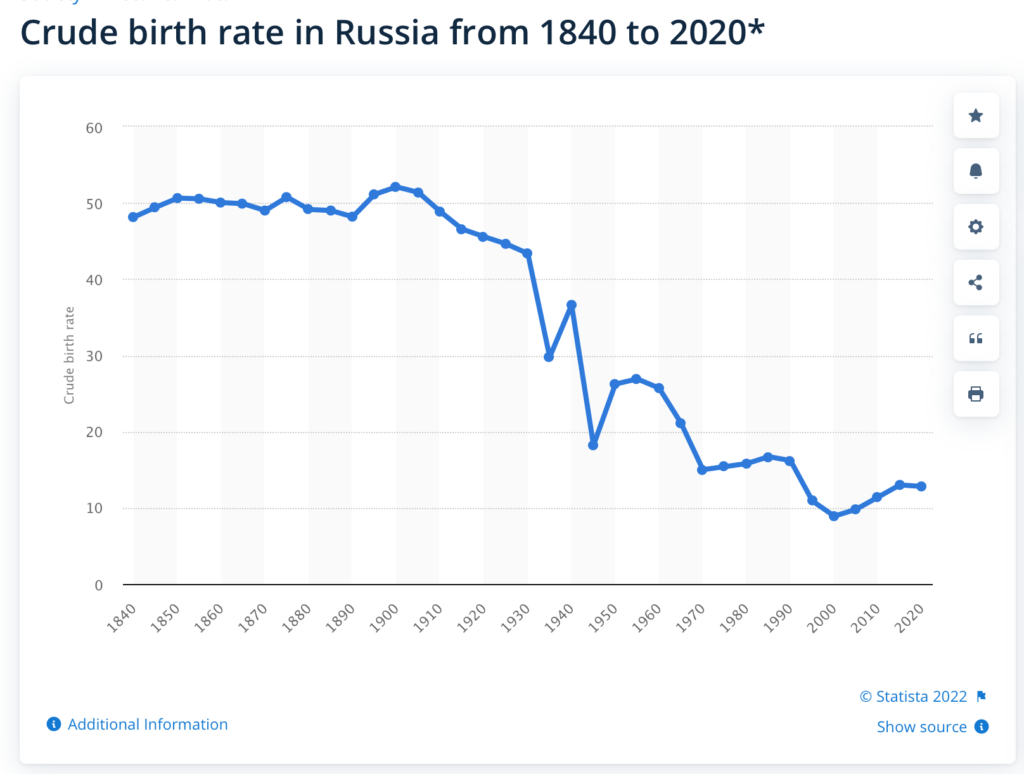

Under Minister of Defence Sergeyev, the Russian military was reduced from from 1.8 million in 1997 to 1.2 million by January 1999. The Russian Army bore the brunt of these cuts for two reasons. The first reason being that the Russian Army comprised the largest personnel authorization so a 1/3 cut to personal would fall disproportionately on the army. The second determining factor was based on performance. The performance of the Russian Army in Chechnya was abysmal. Yet the cuts to the Army were not evenly distributed. There was some attempt to link cuts to accountability.

Motorized rifle and tank divisions and brigades, the backbone of the Russian Army since the glory days of the 1940s, dramatically underperformed expectations and as such bore the brunt of the cuts. An almost infinitesimal bright spot was that the elite “Taman Guards” 2nd Guards Motor Rifle Division and Kantemir 4th Guards Tank Division were no longer going to be the only combat ready heavy divisions (at least on paper) in the Russian Army.

Sergeyev announced in August 1998 that there would be six divisions and four brigades elevated to the same standard as the elite “Taman Guards” 2nd Guards Motor Rifle Division and Kantemir 4th Guards Tank Division. The lack of quality personnel, even in these favored units, continued to be a problem exacerbated by a lack of fuel for training and a shortage of well-trained junior officers prevented all six divisions and four brigades from having uniform levels of combat effectiveness. But now there were all least there was no more than two combat capable heavy divisions in the Russian army. The “Taman Guards” 2nd Guards Motor Rifle Division and Kantemir 4th Guards Tank Division remained elite divisions in the Russian army, but for the first time in at least a decade these units were no longer unique.

The VDV short for Vozdushno-desantnye voyska are the Russian Airborne Forces had long been considered elite forces in the Soviet Army. A proud organization, the VDV relish in their unique status as confirmed by the fact that they have their own holiday, August 2, Paratroopers’ Day celebrates the birth of the Soviet Airborne and is celebrated throughout Russian and in many former countries of the Soviet Union. VDV units tended to attract the most highest performing conscripts and had a larger cadre (although small) of “contract” soldiers (read professional soldiers) relative to the rest of the Russian army.

To provide historical context, the VDV led the initial successes in the invasion of Afghanistan as most of the 700 covert troops, along with KBG and GRU special forces troops. On December 27, 1979 they effectively decapitated the Afghan government in less than two days. The 103rd Guards ‘Vitebsk’ Airborne Division led the way for the main force invasion when they landed at Bagram airport on the morning of December 27, 1979. Soviet Airborne troops were withdrawn from the country after the Afghan government was replaced with one compliant to the Soviet Union, The VDV existed to make war, not keep the peace and the war fighting was done.

The VDV had to be reintroduced as the occupation of Afghanistan failed. Regarded as one of the few Soviet forces to have fought bravely and effectively against the Afghan mujahideen the entire war, their helicopter borne operations suffered greatly with the introduction of American Stinger missiles to the conflict. Despite these hardships they were soldiers who had a reputation for achieving good results in Afghanistan when most of the Russian Army proved ineffective.

VDV forces were so highly regarded before the First Chechen War that Pavel Grachev publicly boasted that he could defeat the Chechen separatist “in a couple of hours with a single airborne regiment”. The reality pf Chechnya was significantly different than expected. The VDV were considered to have underperformed significantly in Chechnya and as such were forced to undergo a reduction in force.

In spite of this “black eye from the First Chechen War, Russian VDV forces were considered elite forces and the most capable, light infantry/light armored troops that the Russian Army had at its disposal in any numbers. This perception holds true in 2022.

Russian Naval Infantry, referred to in the West as Russian Marines, were completely spared any cuts coming out of the First Chechen War. A small force to begin with, they were judged to have “performed competently” in the First Chechen War which meant they dramatically over performed relative to the rest of the deployed force. Russian Naval Infantry are considered elite forces in the 1990s and that reputation carries forward into 2022.

When the Death You Predicted Finally Knocks on the Door…

On August 9, 1999, Vladimir Putin was appointed (not elected) as one of three first deputy prime ministers.

On August 16th, the State Duma approved Vladimir Putin‘s appointment (not election) as prime minister making him Russia’s fifth prime minister in fewer than eighteen months. On his appointment, few expected Putin, as a virtual unknown to the general public, to last any longer than his predecessors. Putin was initially regarded as a Yeltsin loyalist. But events were soon to prove a different game was afoot.

In September 1999 three apartment building in Moscow were blown up killing 300 people and injuring 1000. Rumors had it that it was not Chechens but the FSB (rebranded KGB) and it is alleged that FSB officers were actually caught by the Moscow police planting of some of the bombs.

As a result of these attacks, by December 1999 the Second Chechen War was in full swing. Yeltsin was forced to face the fate he has so narrowly avoided in 1996.

A tired, defeated and broken man, Yeltsin surprised the nation by resigning in his Traditional New Years address on December 31, 1999.

Vladimir Putin, a former KGB officer, former head of the KGB successor organization (FSB ) in 1998, an unknown the Russian public and a man never elected to any office in his life, assumed the office of President on Russia on Jan 1, 2021.

Unknown to the public, Putin did everything he could to stack the deck in his favor. Long time presidential aspirant Anatoly Chubais mysteriously chose not to run for president in 2000 despite planning to do so for more than three years. Extremely popular Alexander Lebed chose not to run for president in 2000 surprising many pundits. Instead Lebed chose self-exile as Governor of Krasnoyarsk Krai (read Siberia). The smoothest possible onramp was paved for Putin’s 2000 election as possible, all he had to do was beat the same tired old communist who lost to Yetlsin in 1996 and some free market economist smart guy almost everyone in Russians had never heard of.

Conclusion

Putin and his allies had smoothed the way for a Putin victory in every way possible 2000 by arranging the circumstances for him to run as an incumbent instead of a candidate. With a campaign of image over substance that some went so far to say that Putin intentional assumed the popular “tough guy” image of self-exiled Lebed that had captivated the minds of the Russian public. Putin won ihis first ever election for anything in 2000 with only 52% of the vote and promised to do better next time.

But as Yeltsin discovered the hard way, winning the presidency was one thing, surviving the presidency was another thing altogether. In order for Putin to survive, he was going to have to win in Chechnya with an army that essentially had the same problems (with few exceptions) as the army that was so catastrophically defeated in Chechnya just a few years before.

We will delve into that challenge in The Russian-Ukrainian War, Part VI, Past Performance Is No Guarantee of Future Results…

Series Articles:

The Russian-Ukrainian War, a Series…

The Problem with the Donbas, The Russian-Ukrainian War, Part II

A Funny Thing Happened On the Way to the War, The Russian-Ukrainian War, Part III

The Russian-Ukrainian War, Part V, You Lose the War You Needed to Win to Survive…What’s next?