As a group, few have contributed more to the realization of this Republic than the Marblehead Militia. Militia groups have a long history in Massachusetts with the first recorded militia organized in 1638. It is the Marblehead Militia and their story that is as improbable as it is true; in the case of these brave men, fact is more improbable than fiction.

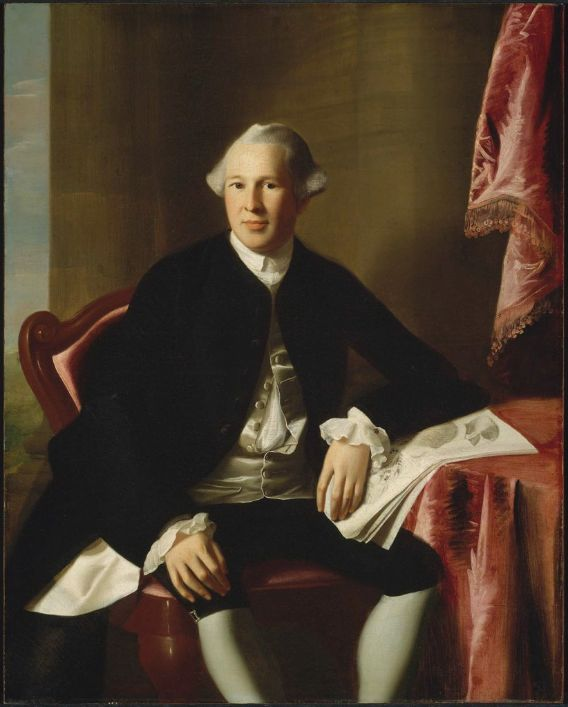

The entire Massachusetts Militia was reorganized in January, 1775, driving out Tory commanders and appointing Jeremiah Lee as commander of the Marblehead Militia with Lt. Col. John Glover as second in command. Not much is known of Jeremiah Lee, but we know Glover joined the militia in 1759 as an Ensign in the 3rd Military Foot Company. Glover was a short, red-headed man, noted as a stern disciplinarian, known to carry a brace of silver pistols and a sword.

The Marblehead Militia, composed as it was of sailors and fishermen, were hardened by the severe winters of New England’s notoriously dangerous waters and used to the rigors and discipline necessary to navigate these coastal waters.

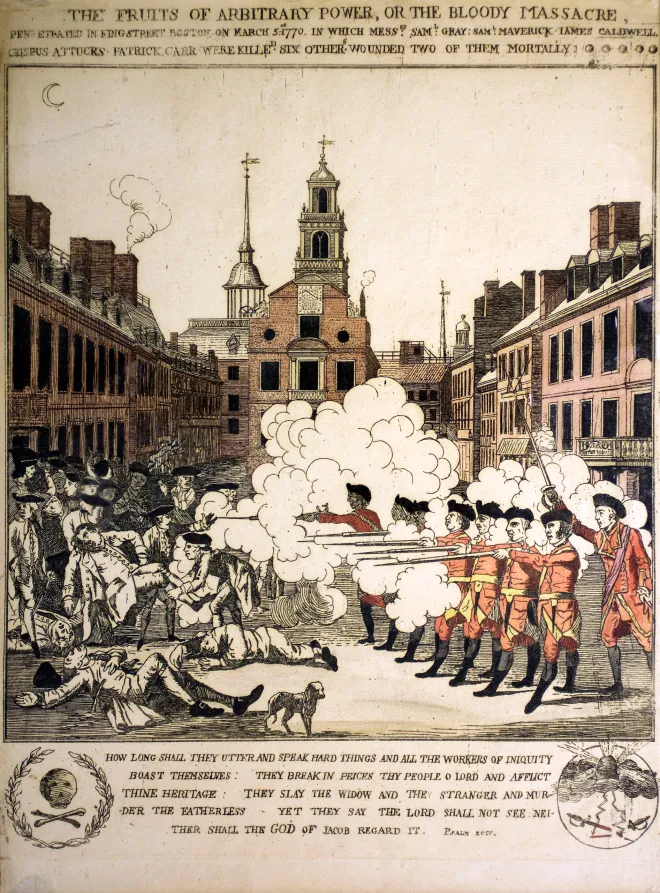

Trade and fishing was the lifeblood of New England, enforcement of “The Intolerable Acts”, (The Trade and Navigation Act, 1651; The Molasses Act, 1733; The Quartering Act,1763; The Sugar Act 1764; The Stamp Act 1765); impressments; seizures of vessels and cargoes; all contributed to a stymied economy and Colonial unrest.

Having already endured these offenses, the volunteers to The Marblehead Militia were hard, determined men. Considered to be smugglers, brigands and pirates by the British, this intrepid band, led by Samuel Trevett partially armed themselves by attacking HMS Lively, capturing powder and arms in a night time raid in early February, 1775.

Although the Regiment was not to be involved in the action at Lexington and Concord, the commanders of the Marbleheaders attended a meeting April, 18, 1775, with Sons of Liberty notables, Samuel Adams, John Hancock and Elbridge Gerry at Weatherby’s Black Horse Tavern in Menotomy. A British patrol rousted Lee and Glover April 19, in an early morning raid. Escaping in their bed clothes, Lee died of exposure from hiding in a wet field a few days later. As a result, John Glover was promoted to Colonel and assumed command of the Regiment.

The Marblehead Militia, nicknamed “Glover’s Regiment” was formally inducted into the Continental Army, June 22, 1775 as the 23rd Massachusetts Regiment with a complement of 505 officers and men. Ongoing enlistments were to expand the total of officers and men to 728.

Washington quickly realized the need for a naval force to disrupt as much as possible the supply line of the British. Washington accepted without hesitation Colonel Glover’s offer of his family’s ship the Hannah and a wharf in Beverly Harbor. In December 1775, Washington, while retaining a Marblehead company for his headquarters guard, dispatched a large portion of Glover’s Regiment to Beverly to man the vessels being recruited and out fitted for service and to protect Beverly Harbor.

When the Continental Army was reorganized January 1, 1776, Glover’s Regiment was reorganized as the 14th Continental Regiment, the designation it was to carry till they were disbanded on December 31, 1776.

Glover’s Regiment became the backbone of General Washington’s “Secret Navy”. They were to man the converted fishing and trading schooners; USS Hannah, USS Franklin, USS Hancock, USS Lee, USS Warren, USS Harrison, USS Washington and the USS Lynch. This small force was to capture 38 vessels carrying arms and supplies destined for the besieged British in Boston. The Regiment was to remain in Beverly until July 11, 1776, when they were ordered to rejoin the main Army in New York. The Regiment arrived at the Army’s Manhattan encampment on August 3rd where they were to remain till summoned to Long Island August 28.

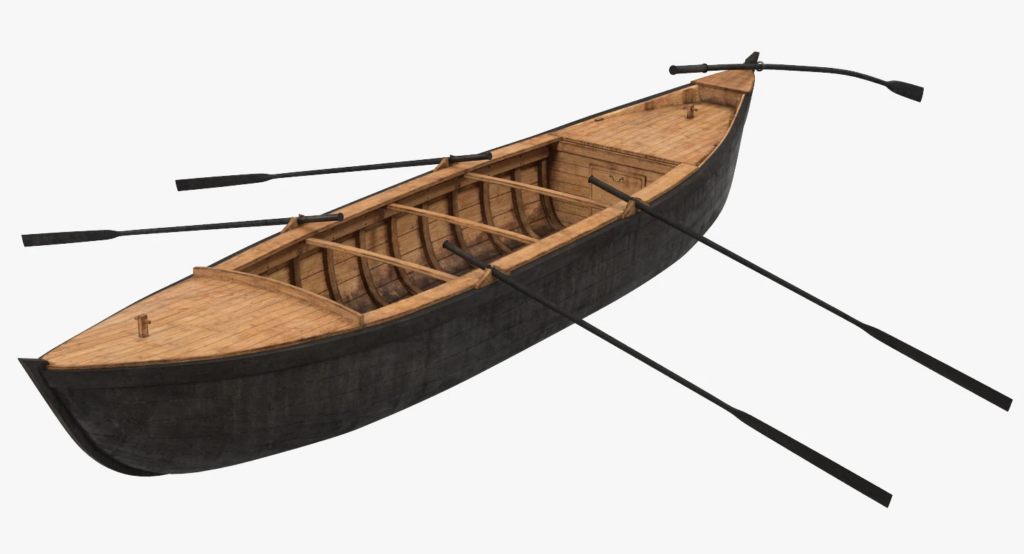

Placed on the line, they were to skirmish with the British; but as the British started digging trenches to place the Army under siege, Washington ordered the 14th Continental to ferry the Army to Manhattan across the mile wide East River. Beginning in a rain storm on the evening of August 29 at 11:00 PM and through the night, ending in a dawn fog, the 14th ferried 9,000 men, the Army’s horses and artillery and other sundry supplies to safety without a single loss of life. The ever watchful General Washing was the last man to board the last boat on that fateful day, arriving in Manhattan at 7:00 AM, August 30, 1776.

Fear of being trapped in New York, Washington started his troops north out of lower Manhattan Island. A British landing at Kip’s Bay quickly routed the militia sent to guard the area. General Washington was unable to stop the hasty retreat; the militia units stopped when they met the 6 brigades moving to their new positions under the command of Colonel Glover who quickly aligned his troops at the breast of a small hill facing the British advance. General Washington ordered a pull-back before the British troops arrived.

Pell’s Point was a different matter altogether; Washington dispatched a brigade under the command of Colonel Glover to challenge a British advance from Pell’s Point, Oct. 18. 1776. In a battle that lasted most of the day, utilizing a series of attack and strategic leapfrog withdrawals, Glover’s 750 men delayed the advance of 4,000 British and Hessian troops. American casualties were 8 men killed and 13 wounded, British casualties were estimated to be 200 British and Hessian soldiers.

The time this engagement consumed allowed General Washington to move his army to White Plains, out of immediate danger. At the Battle of White Plains, the 14th was to man artillery emplacements and later be part of a rear guard as the Continental Army was ferried by elements of the 14th across the Hudson River into New Jersey.

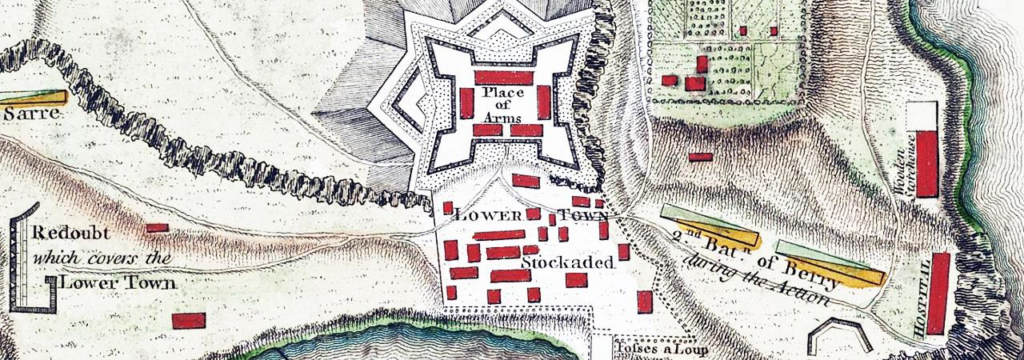

Pursued by the British Army, Washington’s Continentals retreated across New Jersey, the 14th was to again ferry the Army to safety across the Delaware River into Pennsylvania. Washington’s directive to destroy all boats and ferry craft on the north bank of the river was to bring the British advance to a halt. With winter weather making campaigning difficult, General Howe decided to go into winter quarters. Leaving a string of posts across New Jersey, General Howe, accompanied by General Cornwallis was to return to his headquarters in New York. At Trenton, Howe left 1,500 Hessians under the command of Colonel Johann Gottlieb Rall with an additional number further down river at Bordentown under Colonel Carl von Donop.

Washington was assailed by a number of far reaching concerns; a lack of military intelligence in New Jersey, General Lee’s capture by the British and most troubling of all was the coming end of enlistments at the end of 1776. In a letter to Lund Washington, he was to note that without a surge of enlistments, “the game may well be up”. When he received hard intelligence that the British had retired to winter quarters, he determined that the time to strike was at hand.

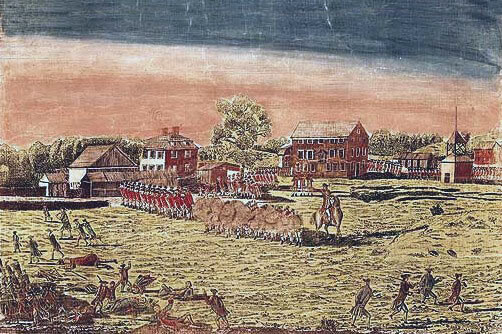

Planned in secret as a three pronged assault, weather was to intervene and the only successful crossing was to be Washington’s. About noon December 25th 1776, Washington began to march his troops up river to McKonkey’s Ferry arriving at dusk in a rising storm. General Washington, concerned about crossing a major river in severe weather, asked Col. Glover his opinion, Glover replied, “Not to be bothered with that, my boys can handle it.” Buoyed by Glover’s confident reply, or as a sign of leadership, Washington was among the first to board for the crossing.

Under the watchful eye of General Greene and Colonel Knox and supervised by Colonel Glover’s Marbleheaders the slow business of ferrying an army, supplies, horses and cannon across the river began. Horses, cannon and assorted supplies were ferried using McKonkey’s ferry craft, while the troops were ferried across in large flat bottom work scows called Durham boats. These craft were handled by the hardy members of the Marblehead Regiment in what turned out to be a blizzard with high winds, serious icing conditions and all in darkness and stealth.

It was a grim General Washington that watched the last of the ferry operation that was to have ended at midnight but hampered by the storm, the time had slipped to near Four AM before the Army was to begin the nine mile march to Trenton. Dividing his forces by sending General Sullivan and Glover’s Regiment by the River Road, he was to accompany General Greene on the Pennington Road into Trenton.

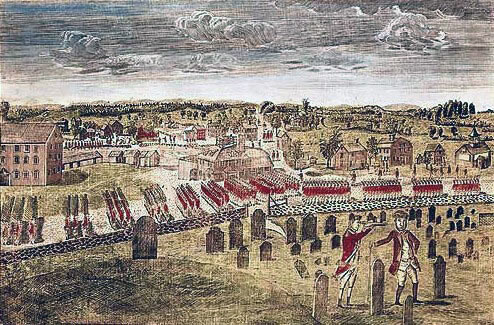

There were a number of factors at work in Washington’s favor; the string of posts Howe had established across New Jersey were under manned, too far apart and left to forage for supplies to feed the men. The Hessians were harsh in their treatment of rebels and loyalists alike, this led to retaliation by rebel groups, ambushing then dispersing against the foraging Hessians.

Fearing an attack in the week preceding Christmas, Rall’s command had been on high alert; his troops were tired from the long hours, were sleeping off a Christmas celebration and secure in a storm to stop enemy movements. By Happenstance or Providence, both columns reached Trenton at near the same time only adding to the confusion of the Hessians. Colonel Rall was mortally wounded near the beginning of the American attack, the resulting confusion and the rapid American advance quickly overcame the leaderless Hessians.

General Washington was stunned by his own success, expecting a heavy casualty list, he asked first for the Hessian casualties; 22 dead, 83 wounded and 900-1000 prisoners; dreading the answer he asked for the American list; 2 dead, frozen on the march to Trenton and 5 wounded.

Note: future president, Lt. James Monroe was among the more seriously wounded when he led an assault on the Hessian positions.

Washington was understandably concerned that he return his Army to the safety of Pennsylvania which of course meant another river crossing with the captured arms and supplies plus the Hessian prisoners. Some confusion still exists as to how long the return crossing actually took, as there was a near constant flow of intelligence reports and correspondence with partisans in New Jersey.

An intelligence briefing on Dec. 27, 1776 notified General Washington that the British and Hessians had retreated north to Princeton. Accordingly Washington planned an attack on the British forces for December 29, but due to weather and other incidents, this third crossing of the Delaware was not completed till December 31, 1776. This was to be the last of the valiant 14th’s contribution to the Revolution as enlistments ended and many of the men returned home to New England, many to be smugglers and privateers.

The contribution by local ferry and river men cannot be overlooked but without the dedicated efforts of the 14th Continental, perhaps the battles of Trenton and Princeton may never have happened.