Journo entry; Ruby Tuesday

Sippin a coffee here, reminds me of the day when I told the Dan-knee, the…

And in conclusion

Sipping a coffee in like 9 degrees, I'm fine, I'm fine, thanks for asking A…

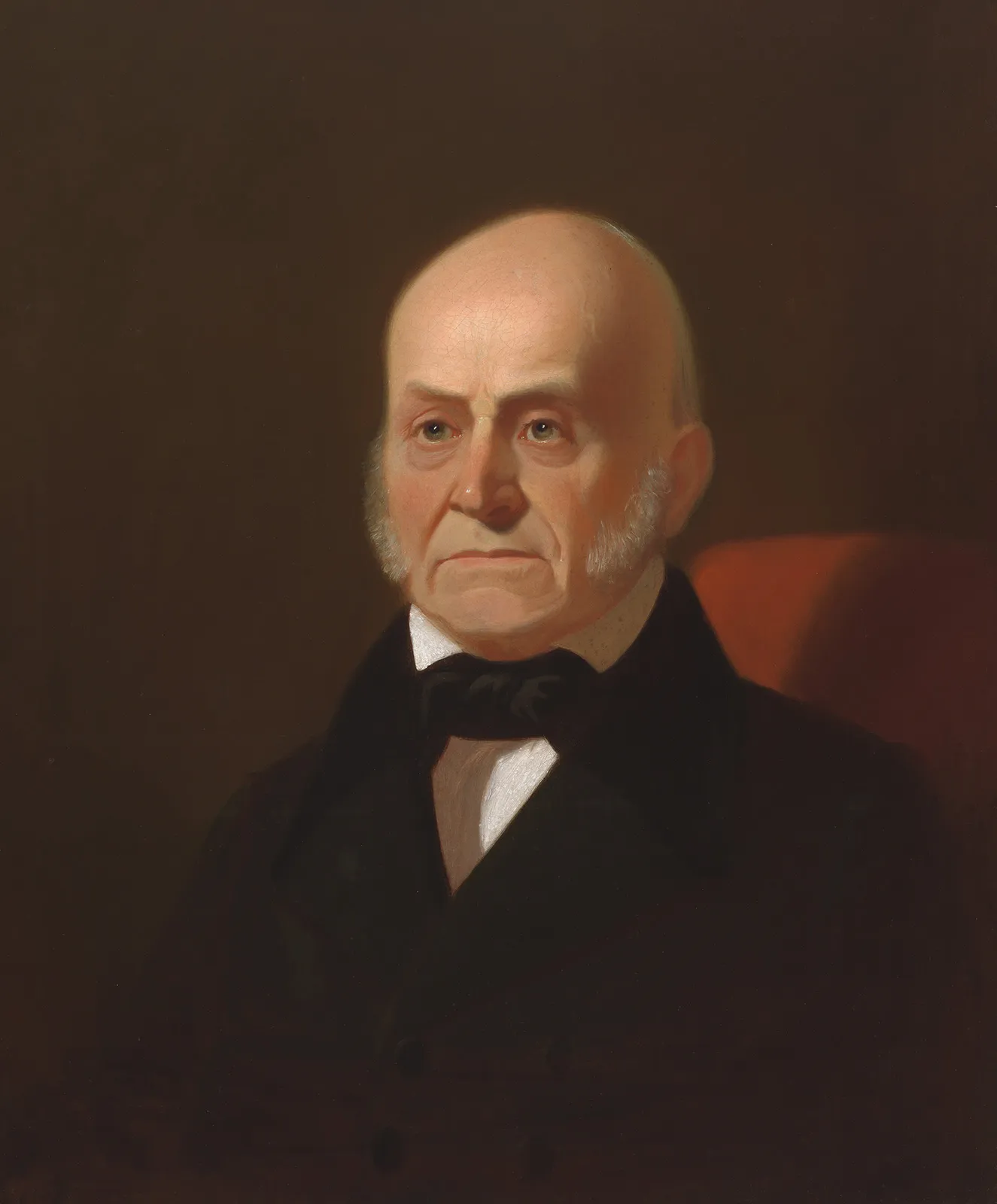

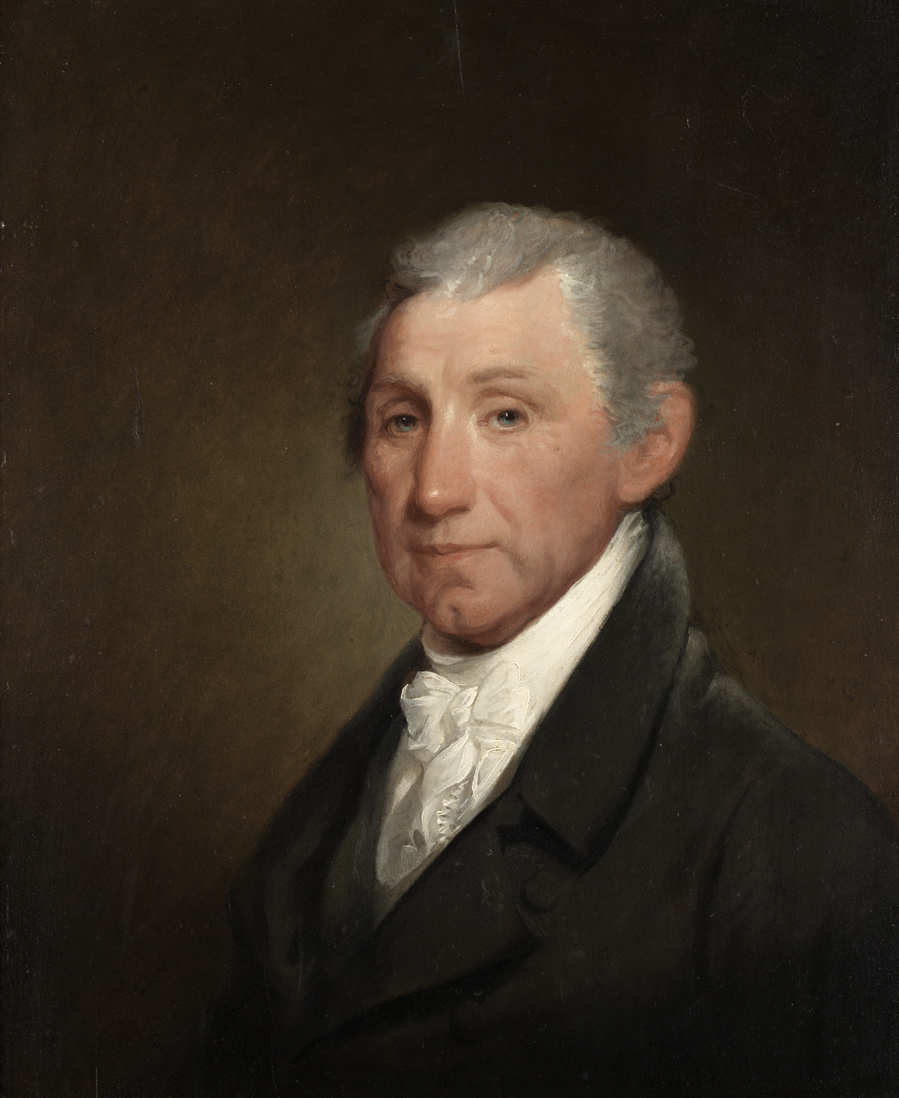

The United States and its Formative Years… Part 7

The Administration of James Monroe James Monroe was elected President with 183 electoral votes and…

Four minutes

Sippin a coffee here, I didn't forget, was rather busy yesterday, about to get busy…

Gold, silver… wisdom

Sipping coffee here, King Solomon, didn't ask God for gold or silver, he got those…

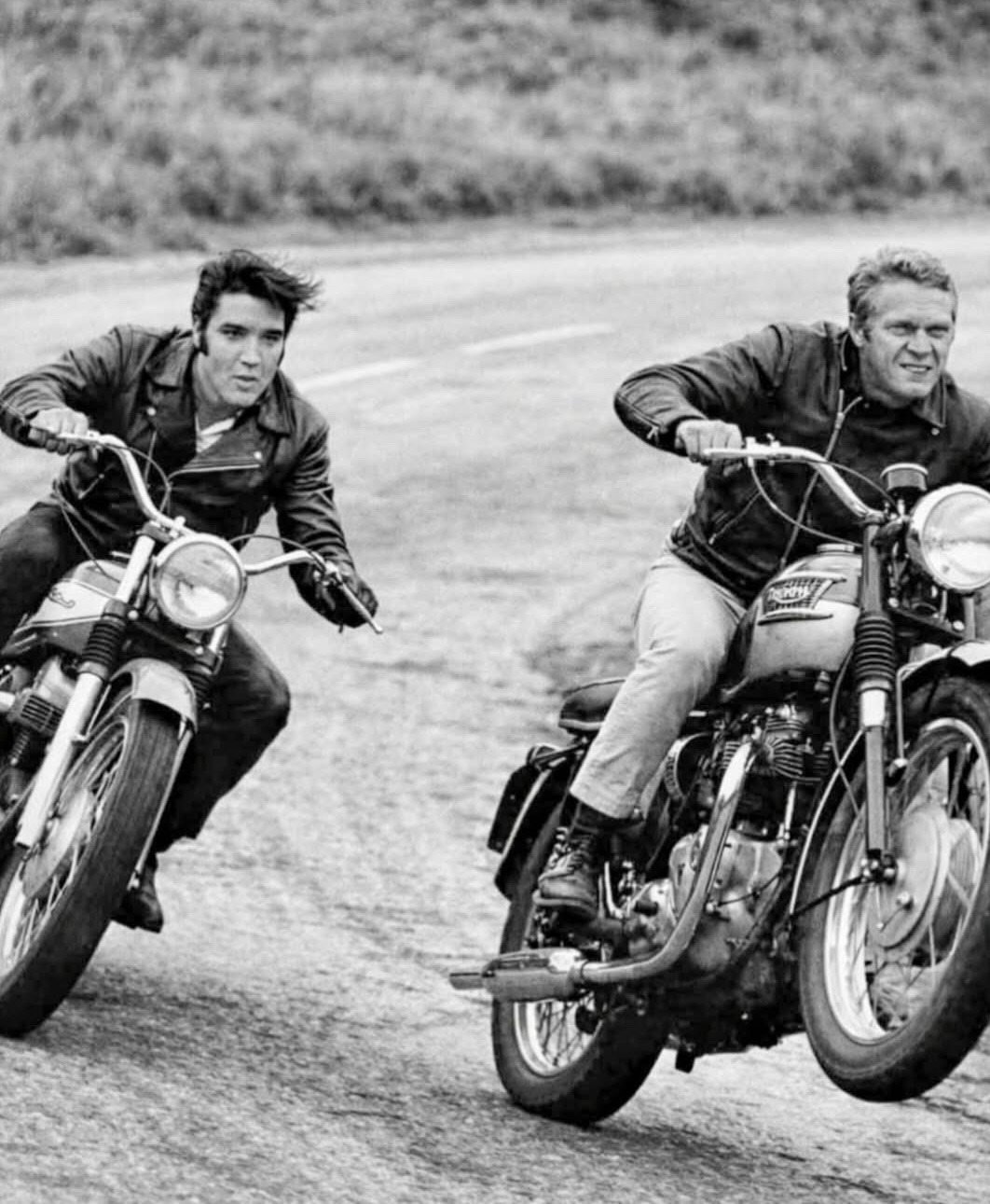

From a different angle on this Firearm Friday

Sipping my coffee, I look nothing like Andy, well, maybe his expression, his posture and…

For comparison purposes only

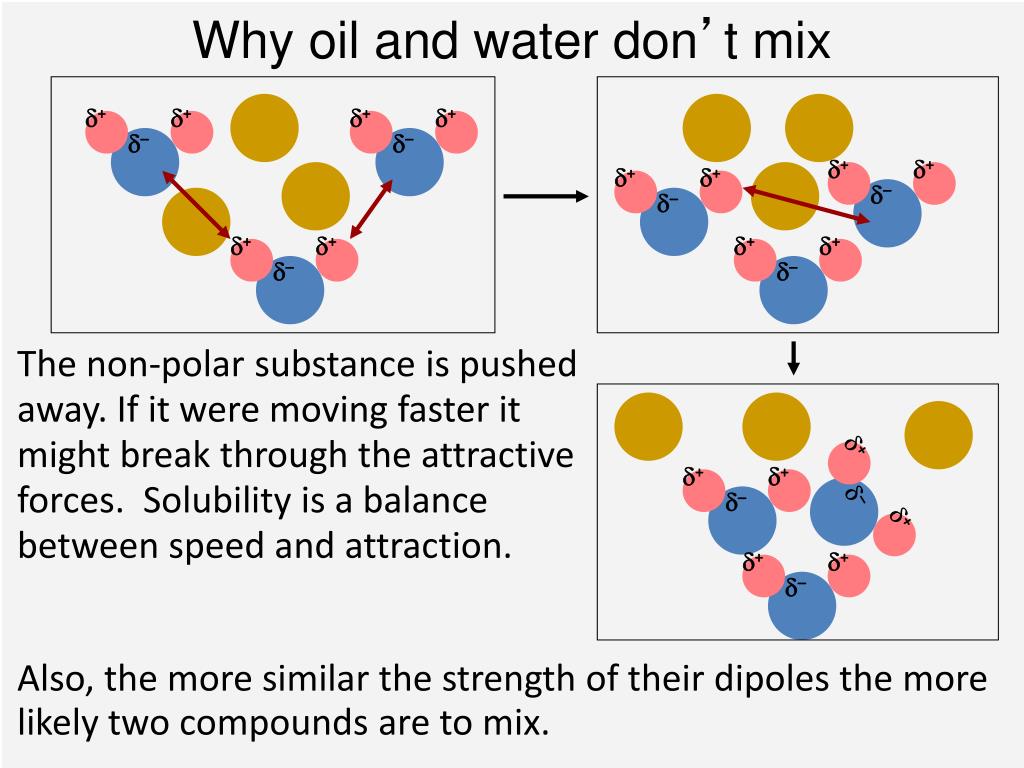

Sipping coffee,if I can get through this without wordpress hating on me, it'll be far…

Tolerance is not a Christian virtue

Sippin a coffee here, was just tellin ratdog that, got the look of how you…

Yeah, I said it :)

Yesterday, stuff to do, so I was like Filling out some paperwork, for the rather…