The Battle of New Market

Today marks the 161st anniversary of the Battle of New Market. The Battle took place…

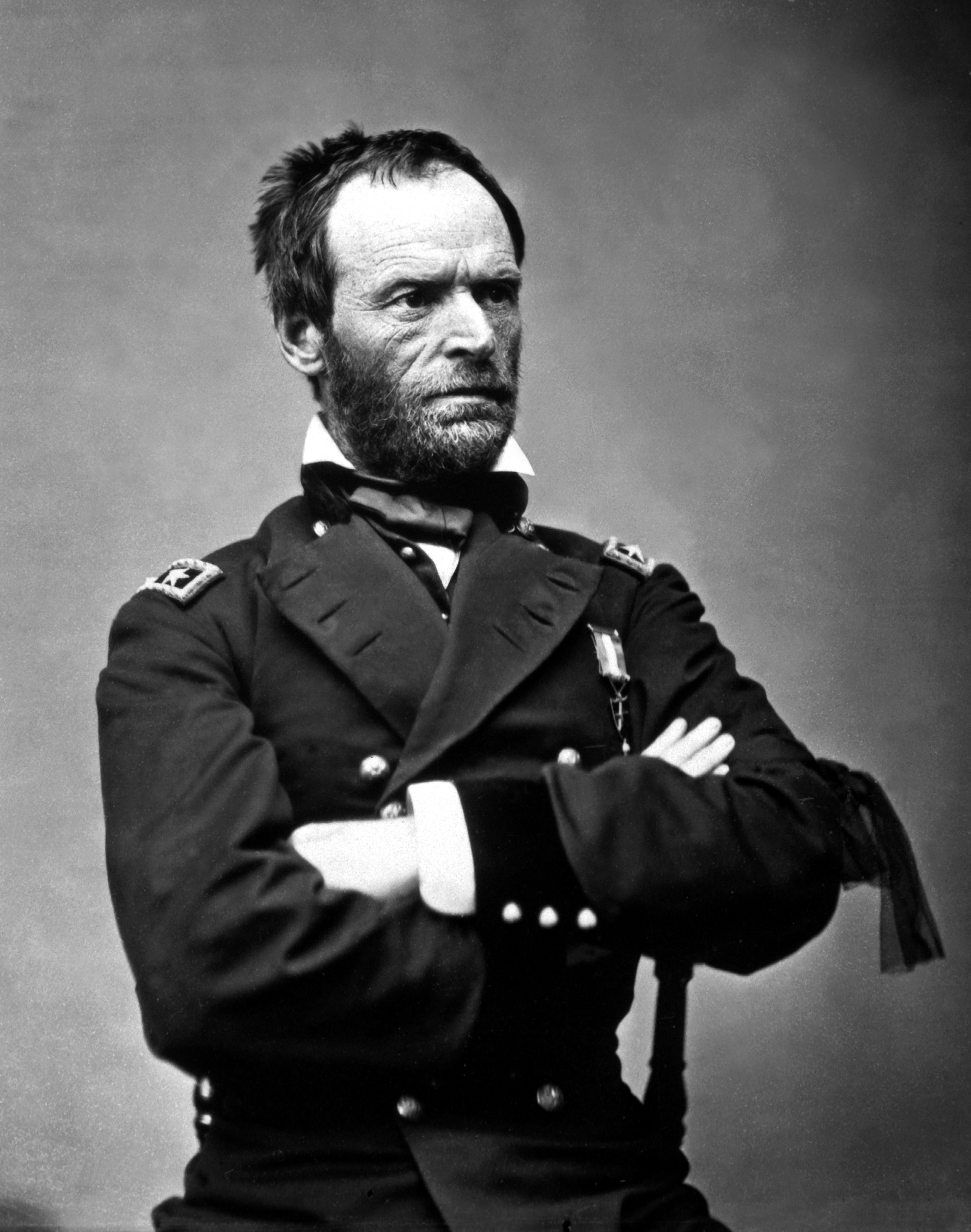

William Tecumseh Sherman

A name that was both revered and reviled; his concern for his men earned him…

Trouble in Syria

After a few years of relative peace, civil war has erupted in Syria again. Turkish-backed…

Four Score and Seven Years Ago

Those words, some of the most famous in US history, were the beginning of Abraham…