The Fatal Flaw in ‘Social Justice’

David Solway for pjmedia.com

In his masterful study of how societies descend into totalitarian stasis and economic decrepitude, “The Path to Tyranny,” Michael Newton points out that what we call “rights” are inherently problematic and often misleading. “Politicians promise the right to high quality education, the right to free or affordable health care and housing, and many other so-called rights.” The political affectation of social compassion and legislative concern for the less privileged among us is a sure-fire vote-getter predicated on a deliberate or, as it may be, an unreflective policy aimed at social betterment. One way or another, our politicians have lost the plot, and the electorate, for the most part, is either deceived or befuddled. The problem, however, is clear: such promised rights are not genuine rights.

The distinction that Newton proposes is as brilliant as it should have been obvious. Such faux entitlements are not rights but “benefits at the expense of others.” The distinction rides on the integrated concepts of fairness, property, and price. As Newton explains, “The rights to private property, free speech and freedom of religion are true rights because they have no cost.” They are intrinsic to the constitution of the democratic state. Whereas, “the ‘rights’ to education, housing, and health care cost the providers who must supply them for free.” Such “rights,” as he says, are “benefits,” gifts, donations — in effect, bestowals that flow from the supervisory redistribution of other people’s incomes via the mechanism of progressive taxation.

Although such expenditures have nothing to do with “rights,” this does not mean that they are expendable or that a compassionate society should not do what it can, within reason, to care for its citizens. The religious concept of “tithing,” with its roots in the Hebrew Scriptures (see Deuteronomy 14:22 and Leviticus 27:30), is pertinent here. Tithes furnished a way to care for the needs of the less fortunate such as orphans and widows, as well as of the priestly class, or Levites, who did not own land or, as we would say today, the means of production. A caring and rational society will adopt and adapt the concept in order to provide for those in need while rewarding — or refusing to unduly penalize — its hardworking, self-reliant, risk-taking, entrepreneurial, and productive class of citizens.

The calculus is delicate and elusive, but a reasonable compromise would need to be found between want and plenty. One way toward achieving this difficult balance is to recognize the difference between a right and an option and to cease confusing both the terminology and the concept. And to recognize, too, that the unfortunate are often the victims of their own lapses and failings, that a parasitical class does in fact exist, and that the self-proclaimed victim caste are not Levites.

Thomas Sowell’s new book “Social Justice Fallacies” explores the subject in lucid detail, working out the notion of “reciprocal inequalities,” that is, inequalities between individuals and groups that are built-in by nature, heredity, ethos, and culture — for example, by racial aptitudes, by climate and geography (a thesis expounded by Jared Diamond), by the past in terms of “developed capabilities,” and by personal singletons. People excel or do not excel in particular domains and disciplines for reasons that may have nothing to do with discriminatory biases. Indeed, “Group equality in either incomes or capabilities is hard to find” in any given society or nation anywhere on the planet. In a society with equal opportunity and equal standards applied to all, “circumstantial disparities” are factors whose outcomes cannot be controlled or smoothed over to produce a level playing field.

Difference is an indelible fact of life. Individuals and groups do well in different ways, which explains asymmetric contributions and activities associated with different races, nations, and cultures. These are not necessarily signs of social injustice or prejudice. There are more of X in one field, more of Y in another, where natural capacities and historical aptitudes prevail.

Ironically, demographically underrepresented groups have throughout history outperformed dominant majorities — Sowell offers a veritable trove of such instances. “Majority domination” often turns out to be a myth and a catchword exploited by “social justice” crusaders. In any event, there is no country anywhere in the world, Sowell writes, “that has had the proportional representation which [social justice advocates] have made a criterion.” Favoring such presumably disparate classes through legislative fiat and wealth redistribution is not a “right” but a political choice that requires the forcible sequestration, chiefly through taxes, of other people’s property and assets, as well as of their rightful opportunities.

Justice in the widest sense entails a tricky calibration between needs and resources, between those, as the old saw has it, who ride in the wagon and those who pull the wagon, between grievance and ambition, between unearned and earned dividends, between those who feel a sense of social entitlement and those who should be justly compensated for their labor, spirit, inventiveness, and energy. Such a calibration has nothing to do with affirmative action, fiscal redistribution, or historical reparations — in short, with “social justice.”

There is no cost-free, conceptually entrenched, elemental entity called “minority rights.” Allowances, perquisites, insurances, and subsidies may be regarded as moral obligations but they are not “rights.” They are not constitutional provisions respecting the freedom of the individual within a lawful and well-ordered state in which property — intellectual, economic, physical — is regarded as the basis of a free society and therefore sacrosanct. The problem with “social justice,” as Sowell elaborates, is that it “has no defined meaning” but only “emotionally powerful connotations.” As a result, it can get away with fudging a crucial distinction, conflating a right with a gift, the principle of liberty with the practice of enforced equality. There is a thin line that divides generosity from robbery, gratuity from legalized extortion.

“Social justice” is thus a practice that is easily — and indeed, almost always — abused, leading to misallocated resources, ideological priorities, and the eventual eclipse of both the principle of meritocracy and the sense of personal responsibility. It fosters a sentiment of betrayal in those whose legitimate rights have been displaced by bogus rights and whose contributions to the well-being and prosperity of society are not appreciated or even acknowledged. They bear the financial cost for assigned privileges which, as Newton argues, are for that reason not genuine rights. This is when the wagon begins to bog down.

Ultimately, no viable society can survive “social justice.” It is a killer narrative. It is the road to nowhere good.

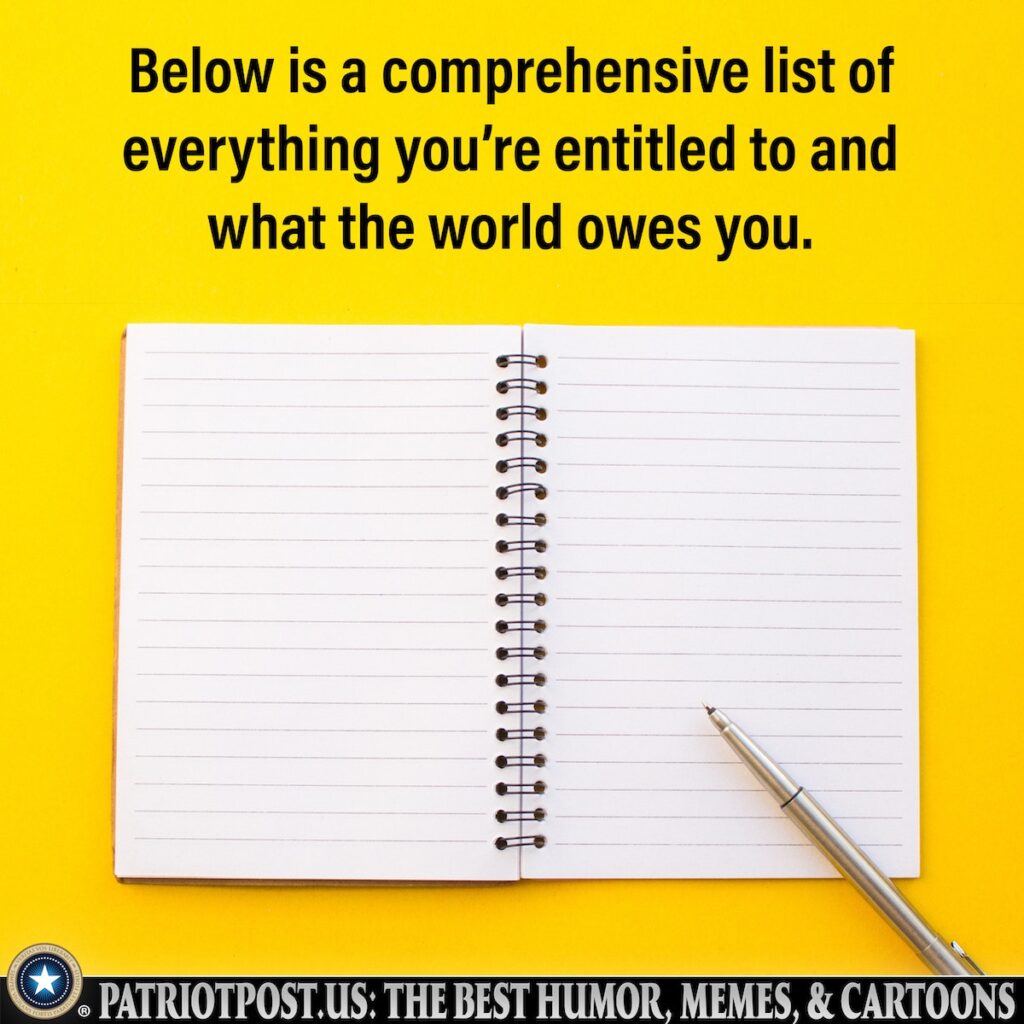

Below is my response to those who believe they are entitled to the efforts of others.