On the morning of 6 December 1917 in Halifax harbor a French cargo ship, the Mont Blanc detonated. It was one of the largest man-made, non-nuclear explosion in recorded history. It released the equivalent energy of roughly 2.9 kilotons of TNT. At least 1,782 people were killed, largely in Halifax and nearby Dartmouth, by the blast, debris, fires, or collapsed buildings, and an estimated 9,000 others were injured.

The Mont Blanc was bound to Bordeaux from New York via Halifax carrying a mixed cargo of TNT, picric acid, guncotton and Benzol, a petroleum based fuel containing benzene and toluene, when the explosion occurred. She was travelling at approximately one knot, well under steerage speed, when she collided with the Norwegian flagged SS Imo, who was on the way to New York to pick up a load of relief supplies for Belgium. It was 0845.

The damage to Mont Blanc was not severe, but barrels of deck cargo toppled and broke open. This flooded the deck with benzol that quickly flowed into the hold. As Imo‘s engines kicked in, she disengaged, which created sparks inside Mont-Blanc‘s hull. These ignited the vapours from the benzol. A fire started at the water line and travelled quickly up the side of the ship. The captain quickly realized the ship was going to explode and gave the order to abandon ship.

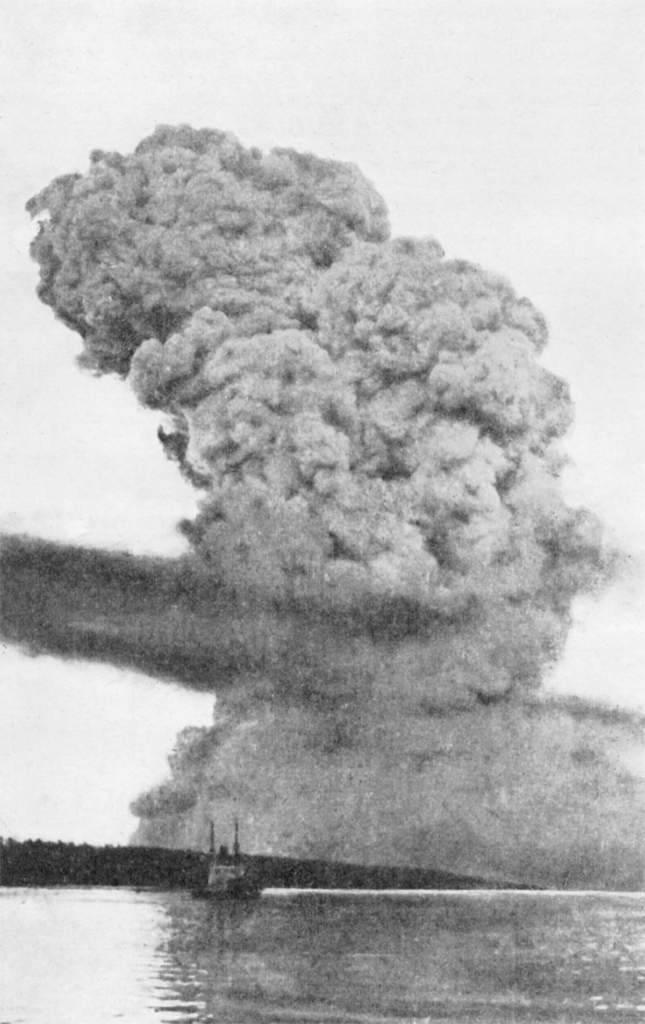

At 0904, the cargo of TNT and guncotton detonated. The blast ripped the Mont Blanc to shreds and tossed debris miles. The Mont Blanc’s anchor, weighing half a ton, landed more than 2 miles away at Armdale. The explosion was heard and felt as far away as Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton, both more than a hundred miles away.

The blast leveled every building in a 1.6 mile radius. It was so powerful of an explosion that the floor of Halifax Harbor was momentarily exposed because of the water displacement. That displacement caused a tsunami that destroyed the Mi’kmaq settlement in Turtle Grove across the bay. As many as 1,600 people were killed in the initial blast with at least 9,000 more being injured. The Halifax Explosion Remembrance Book identifies 1,782 victims, but the exact toll isn’t known for certain.

1,630 homes were destroyed in the explosion and fires, and another 12,000 damaged; roughly 6,000 people were left homeless and 25,000 had insufficient shelter. The city’s industrial sector was in large part gone, with many workers among the casualties and the dockyard heavily damaged.

Reconstruction efforts commenced immediately. The dockyards were operational by January of 1918. Housing however took longer, with the hardest hit section of Halifax, Richmond, not being completed until 1919.