It is estimated that there were only about 3,000 mountain men and trappers at the peak of the fur trade. Some would become legends in their own time, others would be recognized later. That some were anti-social outcasts from society only added to the myths, tall tales and downright prevarications that are part and parcel of “The Mountain Men”.

Here are a few more of these intrepid souls, some of their adventures and their contributions to the knowledge of what was an unexplored wilderness.

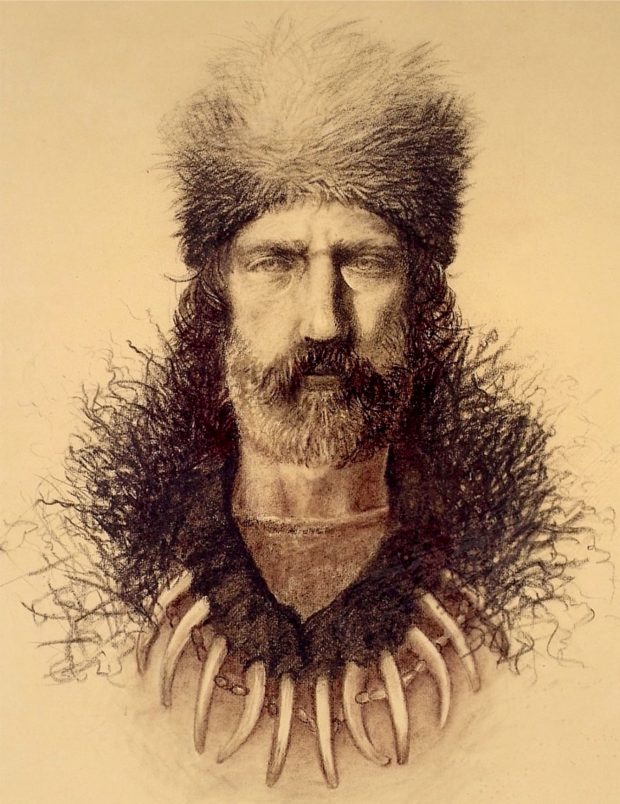

Hugh Glass was born in 1783 and much of his early life is a mystery. He suddenly appeared in St. Louis with a number of Pawnee Indian delegates there to meet with government authorities in 1821. In 1823 he joined William Ashley’s trapping expedition to the upper Missouri. He was wounded in an Indian attack, June 2, 1823 but remained with “Ashley’s Hundred”. After regrouping at Fort Kiowa, Andrew Henry, Ashley’s partner, Hugh Glass and others headed for the Yellowstone River. Glass surprised a mother Grizzly with two cubs while scouting and hunting. His hunting partners managed to kill the bear but not before he was severely mauled. Left for dead by two men left to bury him, he would not only survive, but dragged himself 200 miles back to Fort Kiowa. In February 1824 in another Indian skirmish that killed two men, Glass eluded the Indians and returned to Fort Kiowa carrying only a knife and flint. He would seek the men who left him for dead but never killed either of them. His life would end on the Yellowstone River in another fight with hostile Indians in the spring of 1833 at the approximate age of 50.

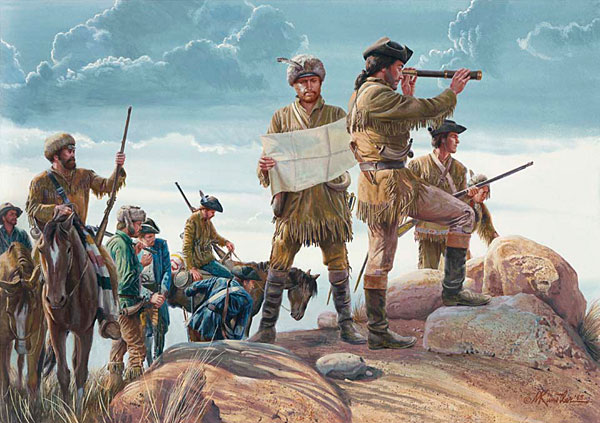

Etienne Provost was born in a small village south of Montreal Canada in the year 1785. Little is known of him until he emerges as a player in the St. Louis fur trade in 1815. From 1821 to 1830, he trapped and traded with the Indians across much of the present day states of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona and Utah. Although Jim Bridger is credited with being the first man to see the Great Salt Lake, Provost and his trappers were in and around this area for more than a year before Bridger entered the area. Provost would begin to lead supply trains to the annual trappers rendezvous, exiting the fur trade for good in 1838. Provost would serve as guide to the mapping expedition of “Papa Joe” Nicollet in 1839 where he would meet John Fremont. He would continue to serve as a guide until 1849. He died July 3, 1850 at the age of 65 in his St. Louis home.

Related: Of Mountain Men and Map Makers

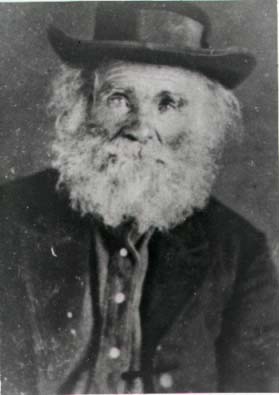

William Sherley “Old Bill” Williams was born January 3, 1787 in North Carolina and moved with his family to present day Missouri around 1795. Fluent in many Native American languages, he was invaluable in negotiation with the tribes before and after the War of 1812. He saw military service as a sergeant and scout in the Mississippi Mounted Rangers during the War of 1812. After the war Williams began preaching among the tribes and married an Osage woman. Sometime after her death he married a Ute woman and lived with his wife’s Ute family. A skilled trapper, he trapped alone, (the Ute’s called him “Lone Elk”) never revealing where his journeys took him. Known to many of the mountain men, he scouted and guided parties extensively. His association with Fremont’s 4th expedition that began in November 1848 ended in the deep snows of the San Juan Mountains as 10 members of the expedition perished due to starvation and exposure. He would meet his own end at the hands of a band of Ute warriors March 14, 1849 at age 62. (Rumors of cannibalism would swirl around “Old Bill” and taint John Fremont’s 4th expedition.)

Editors note: I had intended to continue this series every Tuesday, unfortunately, I lost track of what day it was yesterday, and failed to publish this segment of the series. Mea culpa. The series will continue next Tuesday.