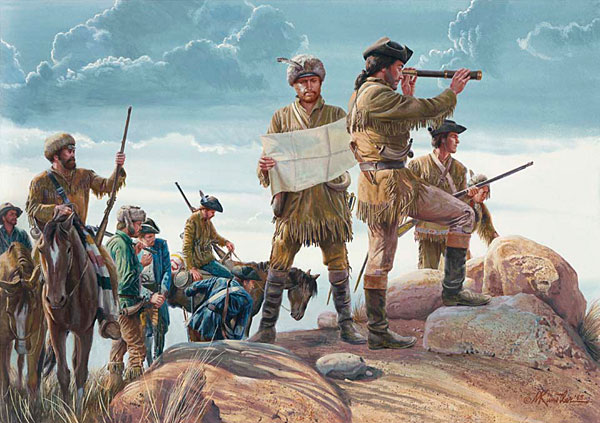

It is estimated that there were only about 3,000 mountain men and trappers at the peak of the fur trade. Some would become legends in their own time, others would be recognized later. That some were anti-social outcasts from society only added to the myths, tall tales and downright prevarications that are part and parcel of “The Mountain Men”.

Here are a few of these intrepid souls, some of their adventures and their contributions to the knowledge of what was an unexplored wilderness.

James Felix Bridger was born March 17, 1804 in Richmond, Virginia, his family moved to the St. Louis area in 1812. Five years later and Jim was orphaned, unable to read or write he was apprenticed to a blacksmith. At age 18 he joined William Ashley’s fur trapping expedition in the upper Missouri River March 20, 1822. He was present at the June 2, 1823 attack by Arikara Indians. It has been rumored that Bridger was involved in the Hugh Glass Affair; subsequent investigations have discredited the story. His involvement in the Fur Trade would dictate much of his travel up and down the Rocky Mountains from present day southern Colorado to the Canadian border and as far west as Utah and Idaho. He is credited with being the first white man to see the geysers and mud pots of what would become “Yellowstone National Park”. His travels took him to the Great Salt Lake; he believed he had reached an arm of the Pacific Ocean. In 1830, he bought out Jed Smith’s fur company and established the “Rocky Mountain Fur Company” and competed openly with Astor’s American Fur Company as well as the Hudson’s Bay Company. His partner Louis Vasquez and he opened a trading post on the Oregon Trail to service the wagon trains in 1843. As the fur trade died, the resourceful Bridger in addition to his lucrative trading post turned to being a guide. In 1850 as part of the Stansbury Expedition, he would scout a new pass over the Rocky Mountains (Bridger Pass) some 60 miles south of South Pass that would become the route of the Trans-Continental Rail Road. In the 1859 Raynolds Expedition Bridger would guide this mapping expedition over Union Pass to explore the towering Teton Range. In 1864 he opened the Bridger Trail into Montana thereby skirting the Bozeman Trail. In 1865 he would scout for the US Army in “Red Cloud’s War”. Suffering several health issues, he returned to Missouri in 1868. He would succumb to his having lived July 17, 1881 at the age of 77.

Christopher Houston Carson (aka Kit) was born December 24, 1809 near Richmond, Kentucky. The Carson family moved to Missouri when he was about a year old. Kit’s father was killed by a falling tree limb when he was 8. That may be the reason he was never learned to read or write; he was illiterate throughout his life. When his mother remarried 4 years later, the headstrong young Kit was apprenticed to a saddle maker in Franklin, Missouri, the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail. Lured by tales of the west, young Kit abandoned his apprenticeship and joined a band of traders and trappers going to Santa Fe in August and arriving in Santa Fe in November of 1826. Carson would settle in with Mathew Kinkead in Taos who would teach young Kit the rudiments of trapping. Kit would learn Spanish and several Indian languages plus the universal sign language of the plains Indians. Kit worked as a wagon driver, a translator and a cook between 1827 and 1829. He was cooking for Ewing Young during the winter of 1828-29. He would join Young’s trapping expedition of 1829. In August of that year the party ventured into Apache country and was attacked. This was Carson’s first combative encounter with the Apache. There would be many more. They would trap and trade their way into Alta California, making their way from Sacramento to Los Angeles returning to Taos in April 1830. Carson would join an expedition led by Thomas Fitzpatrick in 1831 into the central Rocky Mountains. He would spend the next ten years as a trapper and hunter. He was hired as a hunter at Bent’s Fort in 1841. A chance meeting with Charles Fremont turned fortuitous for Carson when Fremont hired him to guide his 1st Expedition in 1842; the mapping of the Oregon Trail from the Missouri River to South Pass. He would lead Fremont’s 2nd Expedition to map the Oregon Trail from South Pass to The Dalles on the Columbia River (1843-44). A near disaster in the Sierras was averted due to Carson’s good sense and skills. Carson would lead Fremont’s 3rd Expedition into California and Oregon of 1845 and be present during the Bear Flag Revolt of June 1846. He would lead a futile rescue effort for Mrs. Ann White, her child and her Negro servant in 1849 that would haunt him the rest of his life. Carson would lead a group to northern California and southern Oregon with seven thousand sheep in 1853. Kit would dictate his memoirs in 1856; the manuscript would be lost, only to surface in a trunk in Paris in 1905. DeWitt Peters would write Carson’s first biography in 1859, Carson would remark,”Peter’s laid it on a leetle too thick”. When the Civil War broke out Carson enlisted as a Lieutenant in Union Army April 1861; he was advanced to Colonel in August 1861. His unit would be involved in the “Battle of Valverde” in February 1862. Carson’s commanding officer Major General James H. Carelton ordered Carson to capture and drive the Mescalero Apache to a reservation on the Pecos River in eastern New Mexico. By March 1863 some 400 Mescalero Apache had arrived at Bosque Redondo. Carleton ordered Carson to initiate actions against the Navajo; by the fall of 1863 Carson began a scorched earth campaign against the Navajo, directed to continue his campaign, Carson entered Canyon De Chelly, burning hogans, crops and slaughtering livestock. The starving Navajo surrendered and began “The Long Walk” that saw stragglers shot and killed. November 25, 1864 Carson led his forces against a coalition of southwestern Indian tribes in a four hour engagement at the “First Battle of Adobe Walls”. General Carleton’s hatred for the Indian drove his treatment of the Indians quartered at Basque Redondo and reports reaching Washington forced a hearing resulting in the decision to close the reservation at Basque Redondo. The experiment known as Bosque Redondo was a complete failure, General Carleton was fired, and as a result the Navajo were allowed to return to their homeland. With the end of the Civil War Carson was appointed commandant at Ft. Garand, Colorado as a Brevet Brigadier General March 13, 1865. He began ranching after leaving the Army; when his wife unexpectedly died it was if his spirit died with her; he died one month later May 23, 1868 at the age of 58.

Richard Lemon Owings (aka Dick Owens) was born October 14, 1812 in Owings Mills, Maryland. He grew up near Zanesville, Ohio, in 1834 he left the family farm and went west with Caleb Wilkins. Little is known of his movements until he meets Kit Carson in 1839. The two would often work together over the next ten years; both had established homes near Taos. In March 1845 they started a farming enterprise but closed the operation to join Fremont’s 3rd Expedition to the Great Basin and California. He would accompany Fremont and Carson over the Sierra Nevada eventually reaching Sutter’s Fort near present day Sacramento. He would leave California in 1850 and return to his family near Marion Indiana, he would marry Emily Miller in 1854. During the Civil War he moved to Iowa, moving again in 1872 to Circleville, Kansas where he lived quietly till his death June 11, 1902 at the age of 89.

Editors note: this wraps up the Mountain Men, next week we start on the Map Makers.