Featured Image: This lithograph by Currier & Ives depicts four of the major inventions of the nineteenth century: the lightning steam press, the electric telegraph, the locomotive, and the steamboat, all of which were developed during the Industrial Revolution.

The United States evolved from a collection of Colonial vassal states in the 17th century to a vibrant and powerful nation by the middle of the 20th century. What helped this collection of diverse colonies to become a world powerhouse so quickly? Was it the land; a myriad of resources; an abundance of energy; a literate workforce? The answer is all of the above; it needed but one more ingredient to make it all come to fruition. The Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution and the United States happened at about the same time and pace. As the colony’s demand for carpenters, wheel rights and blacksmiths increased, the entrepreneurs and inventors began to further what would become American Industry. From humble colonial beginnings, an empire was about to vault on to the world stage.

The Virginia colony and the Massachusetts Bay colony arrived on the east coast of the continent with tools and equipment they were accustomed to using. Tools suitable for carpentry and farming, firearms for hunting and defense coupled with a determination to succeed.

The first large scale industry to rise in colonial America was ship building. New England would become a hotbed of construction, everything from skiffs to English ships of war. This in turn encouraged sail making and rope walks to emerge, farmers to grow flax for sails and hemp for rope. Blacksmiths and forgers began to make metal cleats and sheaves for block and tackle replacing the cranky when wet wood sheaves and cleats of the day. Ship Chandlery with everything from the essential to the insignificant would round out this new industry.

The lack of manufacturing posed a major problem for the colonials. American products were sold at depressed prices while imports into the colonies were priced above what they could be sold for in Europe. This caused many to begin the process of making the products they had previously purchased from the English factors; among them was Virginia planter George Washington.

Washington began the process of making many of the products he had originally ordered from England. In order that he reduce his reliance on English factors, his farms started to produce corn and cereal grain; his blacksmiths made plow shares and harrows, and shod livestock not only for his properties but for his neighbors as well. His coopers began to make cooperage for shipping containers and storage. By 1766 he was no longer growing tobacco and his properties were slowly becoming self-sufficient. A new grist mill allowed him to mill grain for his neighbors. Combined with the surplus from his holdings he slowly liquidated his debt to the English factors.

Washington and his program of self sufficiency would inspire other planters to follow his lead. America’s road to greatness had begun, but the American Revolution would intervene.

Britain continued to dominate world trade after the Revolution as well as industrial innovation. British law prohibited craftsmen from immigrating to America further inhibiting industrial development all the while Americans continued to demand English goods. The lack of cohesiveness under “The Articles of Confederation” and no central government further hindered industrial development and trade resulting in the Constitutional Convention, with the resulting Constitutional guarantees to patent protections.

“The Constitution of the United States of America”; Article1, Section 8, Clause 8, “To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” The creation of protection in the form of patents would propel American innovation.

1789 was a year that would intertwine Catharine Littlefield Greene (widow to Maj. Gen. Nathanial Greene), Eli Whitney and Samuel Slater. Although Slater and Whitney would never meet, their inventions would drive an infant textile industry that was about to undergo an expansion of gigantic proportions.

Kitty Greene (as she was affectionately known by her friends) inquired of Eli Whitney if he could invent a device that would separate cotton seed from cotton fiber without crushing the seed. The result of the conversation would be the “Cotton Gin”, a device that could be constructed with ordinary carpentry skills, but would increase productivity by a quantum leap of 40 fold.

Samuel Slater, in defiance of British law, immigrated to New England in 1789. Offered a full partnership if he could invent a textile mill, his success would lead to him building a number of mills across New England. His knowledge of spinning machines, power looms and how to drive them would make him a wealthy man and drive a thriving textile industry in the United States that would spread south as “King Cotton” made its debut on the world market.

Water power was the power source for pre-industrial America; that would change with the introduction of reliable steam power, mechanical horsepower on demand.

Robert Fulton is the better known name when discussing the importance of steam power. But it is Oliver Evans who made a bigger impact on American industry than did Fulton. Fulton never engaged in large scale industrialization as did Evans. Therefore it is my contention that Fulton’s greatest contribution to American industry was to build and prove that a steam boat could travel from Pittsburgh on the Ohio River to the Port of New Orleans on the Gulf coast and return up river to Pittsburg.

Oliver Evans on the other hand would make numerous inventions of note starting with a mechanical carding machine in 1778. He and his brothers began construction on an automated flour mill in 1783 and granted a patent for his mill in 1790. The year of 1804 saw his first commercial steam engine in his Philadelphia store sawing marble blocks. The demand for his steam engine allowed him to form a major manufacturing center, the Mars Works in 1806. Here they would build steam engines using the latest machinery available. In addition to engines they would make metal parts for agriculture and developing industries. Following Fulton’s lead, Evans would expand to the banks of the Ohio opening the Pittsburg Steam Engine Company but would leave the company in 1812 in order to pursue patent rights violations.

Machine Tools and Metallurgy advanced in a tangled affair as steel became the metal that could handle the stresses of cutting and shaping metals with machines rather than hand tools. Machines had to be robust in order to cut and shape while the cutter did not bend or break.

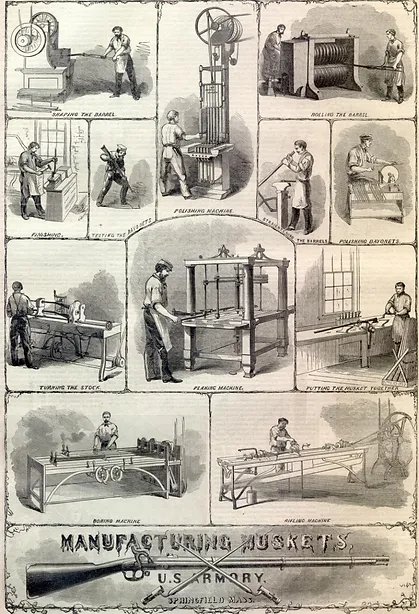

Advances in Metallurgy and a major transition from wood to coal and the higher temperatures coal produced helped increase production and steel of higher quality. The advancements in harder, more resistant metals allowed for the development of Machine Tools. Tools that would in time allow for even more precision in manufacture and Eli Whitney’s long sought dream of interchangeable parts. Capt. John H. Hall developed a system of manufacturing that gained the name “Armory practice” in the United States while it was called the “American system of manufacturing” in England.

Armory Practice: Using machine tools and a defined division of labor, Hall used assembly line (work station) techniques to make guns with interchangeable parts with a semi-skilled workforce. His pioneering work proved the efficiency of mass production.

Britain was the global leader in industrial technology at the end of the 18th century. A global shipping system, plus an internal system of canals and roads gave the English a decided advantage when moving raw materials to centers of manufacturing and finished products to markets anywhere in the world.

While in America the majority of America’s foreign trade was conducted in 6 coastal cities, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Charleston and New Orleans.

It can be said that the industrialization of America created the transportation system we enjoy today. Roads and canals would be among the first government expenditures for the public good. Construction on the National Road from Cumberland, Maryland began in 1815 but as funds dried up construction ended at Wheeling in present day West Virginia in 1818. The State of New York began construction on the Erie Canal in 1817 with the canal open for use in 1825. Seven years of tolls paid the bonds that financed the construction.

Freight and passenger service began on the Mississippi River system with 17 Steam Boats plying the rivers in 1817; that number grew to 727 boats by 1855. Railroads would begin to compete with other transportation modes. Track mileage in 1840 was 3,328, by 1860 there were over 30,000 miles of track. The Civil War would bring its own kind of industrial development but railroads would move troops and supplies for both sides. The Trans Continental Railroad would become a reality in the Utah desert at Promontory Point in 1869. By 1920 there were 254,000 miles of standard gauge track in the United States.

Commercial telegraphy started service in 1844, there were 23,000 miles of telegraph wire by 1852 and supplanted the Pony Express with San Francisco service in 1861. Alexander Graham Bell patented the telephone in 1876, by 1920 there were 13 million telephones in America. The information industry was booming, further spurring industrial growth.

The period between the Civil War and World War 1 was one of phenomenal growth with advancements in Agriculture by John Deere and Cyrus McCormick; Electrification by Thomas Edison; Steel by Henry Bessemer and Andrew Carnegie; Finance by J. Pierpont Morgan. Industrial employment went from 1.5 million in 1860 to 5.5 million by 1900; by 1860 the US Patent office had issued 4 thousand patents; that number grew to 41 thousand by 1914.

It takes energy to drive industry; the demand for coal jumped from 45 million tons in 1860 to 500 million tons by 1900. Coal became the fuel of choice for the railroad industry, plus coal had the capacity to deliver industrial size needs using steam power; it could drive the flywheels, belts and pulleys, but the days of mechanical drive systems were numbered with its competitor soon to emerge.

Electricity arrived as a water powered utility, but coal/electric generation allowed wide spread growth plus a good Rail system only enhanced more growth. Electricity was more than able to handle the demands of industry, soon electrification spread to the cities and towns.

Petroleum, the demand for it is global; the industry started with the first well drilled specifically for oil by Edwin Drake in 1859 but the US oil industry exploded with the Texas well at Spindletop in 1901. Autos and trucks would drive much of that demand with 8.5 million vehicles registered in the US by 1920.

Just before the Civil War the United States ranked 5th in industrial production, by 1890 she had become the global leader as an industrial nation. American industry learned a supply and demand economy from the war that would transform American industry to serve not only the nation but the world as well.

Improved methods of farming and innovative implements drove agricultural production to new highs; advancements in food preparation and shelf life would take transportation to a new level as food products could be moved long distances without spoilage. Another industry had come into its own.

The War to End All Wars would, as all wars do, force innovation and industrialization on a nation at war; followed by a boom that went bust in 1929 only to drive the nation into a deep and long lasting depression. Economists to this day debate the changes wrought by FDR as he sought to pull the nation out of depression.

An intransigent Japan joined by Italy and Germany would force military minds to begin the task of arming for the coming maelstrom. Japanese aircraft would bring war to America with the devastating attack at Pearl Harbor. In the wake of the attack, Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto lamented, “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.”

From its humble beginnings, American Industrial might fulfilled Admiral Yamamoto’s fear.

Author’s Note: The transfer of our industries to foreign interests have me somewhat concerned about our ability to maintain our military readiness should we become embroiled in a war. A nation that cannot maintain its readiness to engage in warfare is a liability to its armed forces as well as its ability to manufacture items for the civilian population. To rely on foreign interests for the goods that allow both the military and civilian sides of a nation to function without supply issues seems to be very short sighted in my humble opinion. WM