Painting of the A Fairey Swordfish dropping a torpedo during the raid. Image courtesy of the Royal Navy

At approximately 20:40 (8:40 PM) local time, November 11, 1940, the first flight of 12 Fairey Swordfish lifted off the deck of HMS Illustrious (followed by a second flight some 90 minutes later) in the final action of a multi tasked operation dubbed, “MB8”.

The planning for MB8 began in the aftermath of the Munich Agreement September 30, 1938. Appeasement to Hitler’s Germany would lead many in the Admiralty to begin the long range planning for British Naval Supremacy in the Mediterranean.

The planning for MB8 came to the fore as Italy declared war in June 1940 and followed up with an invasion of Egypt in September. The conflict for control of the Mediterranean had begun.

With an Italian Army in Libya, a British Army in Egypt, convoys accompanied by war ships crossing and recrossing one another’s course, factor in Italy’s alliance with Germany and conflict was considered a real possibility. Commander in Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham was responsible for the orderly and safe operation of the convoys that supplied the British Army.

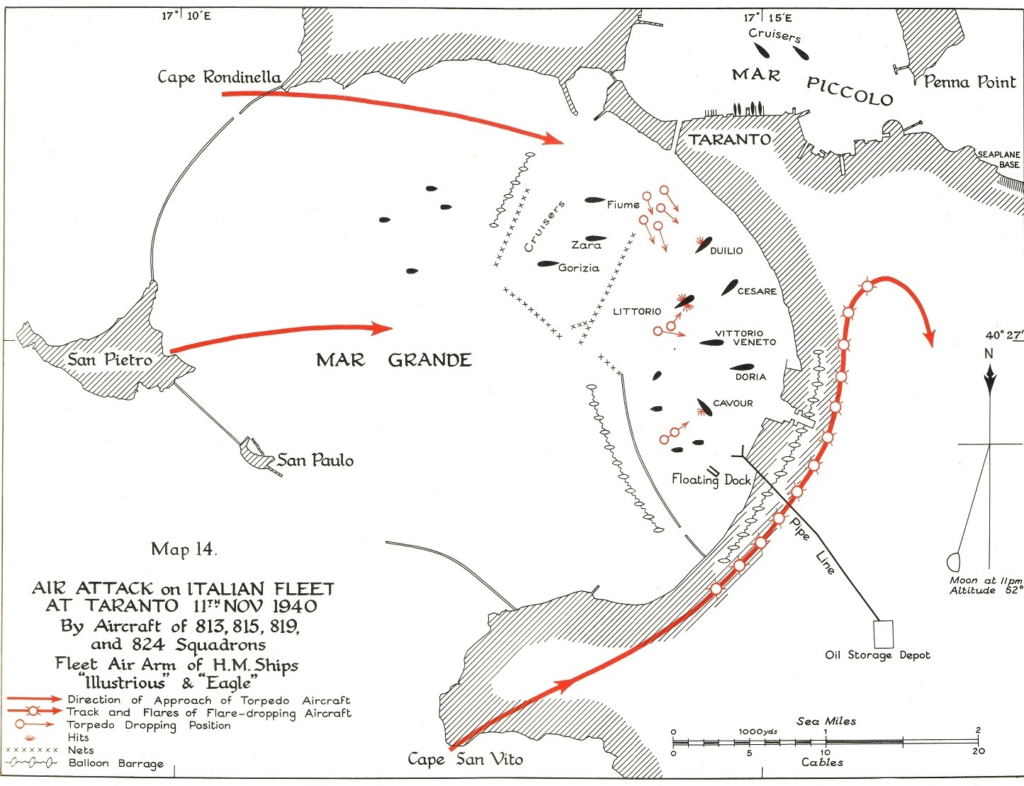

The Italian Navy followed a “Fleet in being” theory that sortied against the British convoys from their base at Taranto consisting of 5 operational battleships, 7 heavy Cruisers, 2 light cruisers and 8 destroyers. To that end Admiral Cunningham was responsible to see that Operation MB8 denigrate the effectiveness of the Italian Navy in interdicting supply convoys to the population of Malta and the British Army in Egypt.

The British were concerned that should the Italian navy be successful, supply convoys to the British Army in Egypt be forced to round the African continent’s Cape of Good Hope and leave the badly needed British outpost of Malta with no reliable avenue of re-supply.

Planning sessions made the case for the Italian Navy’s “Regia Marina” based at Taranto to be the prime target. The planning sessions also made the case for an obsolete biplane to be the prime asset to perform the attack. Designed in the 1930s as a dive and torpedo bomber with night capabilities made the Swordfish the operational choice.

The Italian navy kept tabs on British movements principally by aerial reconnaissance; this made collecting the necessary assets for the attack on Taranto without alerting the Italians of prime concern. Regular British aerial surveillance of the base at Taranto by British medium bombers (Martin XA-22, named the Maryland by the British) kept tabs on the Italian Navy.

In a seemingly discordant series of mixed convoys, “Operation MB8” began November 4, concluding November 11 with the full on attack (Operation Judgement) of the base at Taranto consisted of 5 convoy elements (Operation Coat, Convoy MW3, ME3, Convoy AN6, Operation Crack) that would allow the assets necessary for the raid to be assembled near the Greek Island of Cephalonia (located approx. 170 miles South-East of The base at Taranto) without unduly raising concerns of the Italian Navy.

“Operation Judgement” was originally scheduled for October 21st (Trafalgar Day) but delayed by a fire aboard Illustrious that destroyed two of the Swordfish. A second British aircraft carrier, HMS Eagle was to join Illustrious but a fuel system failure eliminated her participation. In order that Illustrious be able to launch the attack alone, she took aboard five Swordfish from HMS Eagle bringing the number of Swordfish available for the attack to 21.

Several incidents contributed to the British success; first the complexity of Operation MB8 confused the Italians into thinking that it consisted of supply convoys not an offensive. Secondly the Italians had placed a number of barrage balloons to protect against low-flying aircraft, but a wind storm on November 6th had reduced the number of balloons to 27. Lastly but of greater importance was the lack of proper anti-torpedo nets for fully one third of the capital ships in harbor.

The first wave of aircraft consisted of six Swordfish armed with torpedoes, two with a combination of bombs and flares and the remaining four armed with bombs made up the first wave. This was inadvertently split into two sections as 4 aircraft strayed from the group while flying through some scattered clouds.

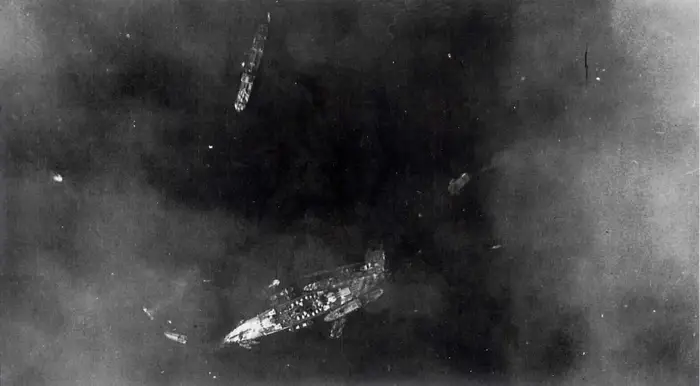

Eight aircraft approached the harbor at 22:58, one dropped flares, joined by another plane, the two attacked and set fire to a series of oil tanks. Three aircraft led by Lt. Commander Williamson attacked the battleship “Conte di Cavour” with a torpedo that tore a huge hole just below her water line; Williamson’s craft was shot down by the ship’s anti-aircraft batteries. The two remaining aircraft, dodging barrage balloons unsuccessfully attacked the battleship “Andrea Doria”. Three planes attacking from a northerly direction launched torpedoes at the battleships Littoria (hitting it with two torpedoes) while missing the battleship Vittorio Veneto.

The bomber force, led by Marine Captain Patch, although having difficulty identifying targets successfully bombed and scored hits on two cruisers and straddled a group of four destroyers.

Nine Swordfish made up the second wave, but a ship board collision damaged two Swordfish forcing one to abort and the final Swordfish to launch some 20 minutes behind the rest of the flight.

Lt. Commander Hale and his flight approached from a northerly direction with torpedoes, bombs and flares. The battleship Littorio was attacked by planes dropping torpedoes again, one torpedo striking her. One of the flights, despite taking heavy anti-aircraft, aimed its torpedo at the battleship Vittorio Veneto but missed. Another craft would torpedo the battleship Caio Duillo, leaving a huge hole in her hull and her forward magazines flooded. Lt. Bayly was shot down by anti-aircraft fire from the Italian heavy cruiser Gorizia after successfully attacking the battleship Littorio; the only craft downed in the second wave. The late launch by the last of the attacking Swordfish arrived some 15 minutes later and made a dive bomb attack on one of the Italian heavy cruisers but was unsuccessful.

Out of the 20 Swordfish that participated in the attack, only two airplanes were lost. Lt. Commander Williamson and his crewman were taken prisoner, Lt. Hale and his crewman would die in the crash of their craft. The rest of the attacking aircraft returned safely to the Illustrious, the final plane landing on her deck at 02:39, November 12, 1940.

British Admirals Cunningham and Lyster wanted to strike the base again the next night, but bad weather intervened.

With the loss of half its capital ships, the Italian navy moved its base of operations to Naples. Contrary to British hopes, five days after the raid, the Italians returned to actively sortie against British supply convoys but were constrained by the added steaming times to interdict the British convoys.

The damaged battleships would undergo substantial repairs. The Conte di Cavour was so severely damaged that she never returned to service. The Caio Duillo was run aground in order to save her and seven months later was returned to service. The Littorio required four months of repair before she too was returned to service.

A modified drop of the torpedoes allowed the British to successfully use torpedoes in the shallow waters of Taranto harbor. A drum with a roll of wire attached to the nose of the aircraft kept the torpedo from nose diving into the water, keeping the torpedo in a flat trajectory as it entered the water.

Lt. Commander Takeshi Naito of the Imperial Japanese Navy was flown to Taranto to investigate the successful attack; this inspection confirmed for the Japanese that they could successfully attack the American base at Pearl Harbor in spite of the harbor’s shallow depth.

This raid on Taranto confirmed for the British the aircraft carrier was of greater value than the battleship due to its ability to attack from ranges that even the big bore guns of the battleship could not reach.