The Olympic Peninsula

Washington State’s Olympic peninsula is home to some of the most diverse combinations of climate, terrain, flora and fauna in the continental United States. At its heart is 7,965 ft. Mt. Olympus, creating a pronounced rain shadow northwest of the peak. At Sequim on the east end of the Strait of Juan de Fuca rainfall measures a mere 16 inches of precipitation annually; while the western slopes of Mt. Olympus averages over 150 inches of precipitation annually. (Psst… those in the know pronounce Sequim as… Skwim)

It is the mountains on the peninsula, circular in layout that create and hold this world within a world; the craggy heights are glacier clad, deeply scarred by the repeated cycles of growth and retreat by the glaciers. The secret that holds this system together is the copious amounts of precipitation in the form of rain and/or snow these mountains and the wide coastal plain to the west and southwest receive.

The mountains of the peninsula are not volcanic in origin although they are constructed of marine basalt as the result of submarine lava flows in their geologic history. Sedimentary sandstones and shales laid down on top of the basalt were mixed, folded and metamorphosed in the process of mountain building as the land was forced up. The Olympic Mountains are a product of “accretionary wedge uplifting” created by the subduction of the Juan de Fuca Plate beneath the North American Plate.

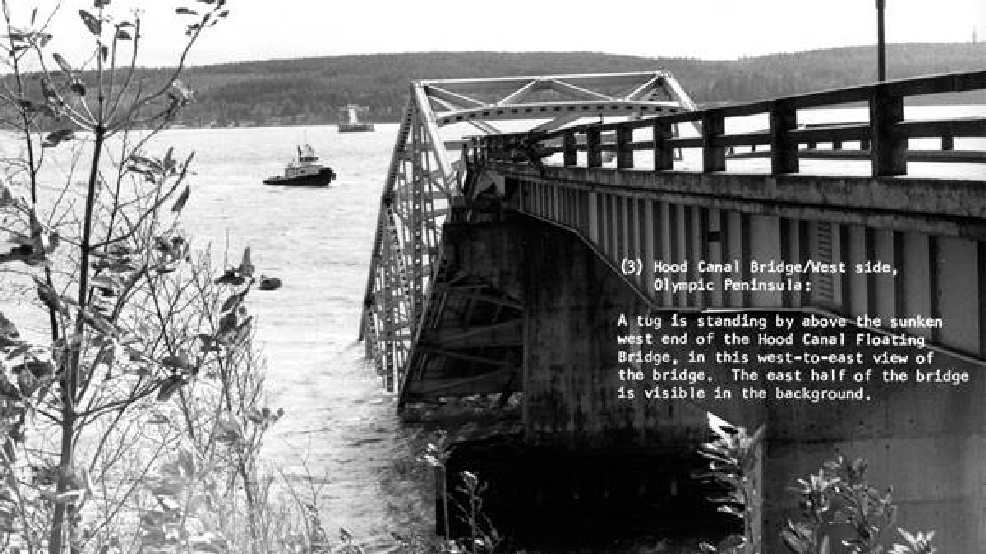

During the Pleistocene Era the Cordilleran Ice Sheet formed both Puget Sound and the Hood Canal in a southern push by the Puget lobe. The ice sheet was hemmed in by the Cascade Range to the east and the Olympic Mountains on the west. Another lobe was forced west between the Olympic Mountains and the mountains of Vancouver Island creating The Strait of Juan de Fuca. The Cordilleran Ice Sheet was known to advance to near its southern limit on 6 occasions and possibly more. The west lobe would advance as well, further scouring the strait. The combination of alpine glaciations and the Cordilleran Ice Sheet would create the steep slopes that border the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the west shore of Hood Canal today.

In an area slightly smaller than the state of New Jersey the peninsula hosts over 150 peaks and summits and nearly 200 perennial ice and snow features such as glaciers and snow fields. Rising from sea level to near 8,000 feet they contain 4 distinct zones, each containing its own list of flora and fauna.

NOTE: as the elevation increases the different zones will share some common flora and fauna. The Subalpine and Alpine zones share the greatest overlap of elevational boundaries.

The Coastal Forest Zone starts at sea level and extends to around 2,000 feet. The famed Rain Forests are found here on the south and west facing lowlands. This zone hosts: 11 different species of trees; 8 shrubs; 11 wildflowers and/or ferns; 3 butterflies; 6 amphibians; 3 reptiles (no naturally occurring poisonous snakes on the peninsula); 13 birds and 9 mammals.

The Silver Fir Zone begins around 2,000 feet extending to a little over 4,000 feet. This zone hosts: 9 trees; 8 shrubs; 10 wildflowers and or ferns; 3 butterflies; 4 amphibians; 3 reptiles; 11 birds and 10 mammals.

The Subalpine Zone begins around 4,000 feet to approximately 5,800 feet. This zone has large tracts of trees interspersed with open areas of marsh and meadow. In the more forested areas there are: 12 species of trees; 10 shrubs and 10 varieties of wildflowers and/or ferns. In the open areas of meadow and marsh there are: 12 kinds of trees; 3 shrubs; 20 wildflowers and/or ferns; 8 butterflies; 3 amphibians; 3 reptiles; 14 birds and 15 mammals.

The Alpine Zone ranges from around 4,800 feet in elevation and includes all lands above the treeline. Here the flora list contains numerous sedges and grasses along with 7 shrubs; 14 wildflowers (no ferns); 4 birds and 6 mammals.

NOTE: The Roosevelt Elk also called the Olympic Elk inhabit the rain forests of Western Washington; the Olympic Marmot is endemic to the mountainous interior of the peninsula. Olympic National Park and several associated wilderness areas occupy major portions of the peninsula.

Two major semi-permanent weather features drive the majority of the weather for the west coast of North America; the Pacific High situated to the north/north east of the Hawaiian Islands migrates north in the summer creating cool, dry weather along the west coast. The counterpoint to the high is the Aleutian Low that centers between Siberia and Alaska along the Aleutian Island chain. This low pressure system migrates into the Gulf of Alaska in the fall and winter months creating the storms that bring the rain, snow and wind that makes up the storm season on the peninsula.

Another weather feature that brings large amounts of moisture is “The Pineapple Express” where the polar jet stream picks up moist warm air in the latitudes of the Hawaiian Islands and streams it to the west coast of North America in a narrow stream that can persist for days. While the Pineapple Express is mainly a rain event, the storms that originate in the Gulf of Alaska are rain, snow and wind events.

The cyclonic winds that drive these storms sweep out of the southwest and pour some 150 inches of rain annually on the peninsula from sea level to over two hundred inches on the mountain peaks. The height of Mt. Olympus causes it to receive the brunt by accumulating the world’s annual greatest single snowfall while the world’s wettest snow falls on Mt. Olympus’ “Blue Glacier”. Only 160 miles N/W of Mt. Olympus, Mt. Baker in the Washington Cascades receives the world’s greatest annual snowfall accumulation.

Where does all this water from rain and snow melt go? Back into the Pacific Ocean, the mountains drain radially; the Quinault, Queets, Hoh, Bogachiel and Soleduck Rivers flow west (these rivers all host rainforests) directly into the Pacific. The Elwha and Dungeness Rivers flow north into The Strait of Juan de Fuca. The Quilcene, Dosewallips, Duckabush, Hamma Hamma, and Skokomish flow east into Hood Canal. The Humptulilps, Hoquiam, Wishkah, Wynoochee, Satsop Rivers and Cloquallum Creek drain to the south into the Chehalis River and into Grays Harbor.

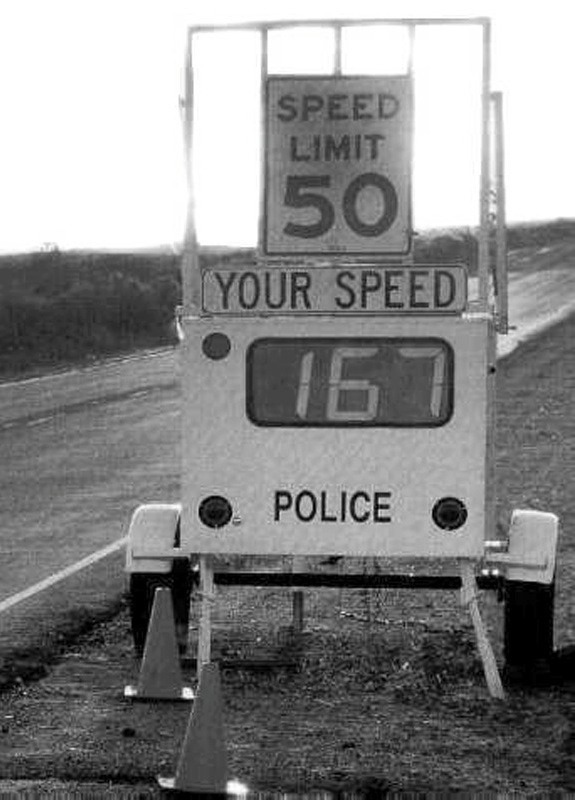

This brings us to the wind; winter storms on the Pacific Coast often exceed the threshold for hurricane force winds, with some estimates exceeding 120 miles per hour. As these storms sweep out of the Gulf of Alaska, their winds counterclockwise rotation cause them to strike the west coast from the south west. The history of the Olympic Peninsula is rife with stories of devastating storms; storms that often came in bands about 24 to 36 hours apart. It was this kind of terrific wind speeds that caused the sinking of the Hood Canal Bridge February 13, 1979.

This world in a world exists in the far northwest corner of our nation. That it is a treasure, there can be no doubt. But United Nations listings that declare much of the peninsula a World Heritage Center sends a message of claim that conflicts with this nation’s sovereignty. The idea that a bunch of foreigners feel they have the right to dictate how much of the peninsula is managed raises the hackles on this old man. We are certainly smart enough to manage “OUR” country without their help or interference.

Walt Mow 2018