The American Revolution…

How it all began… Part 4

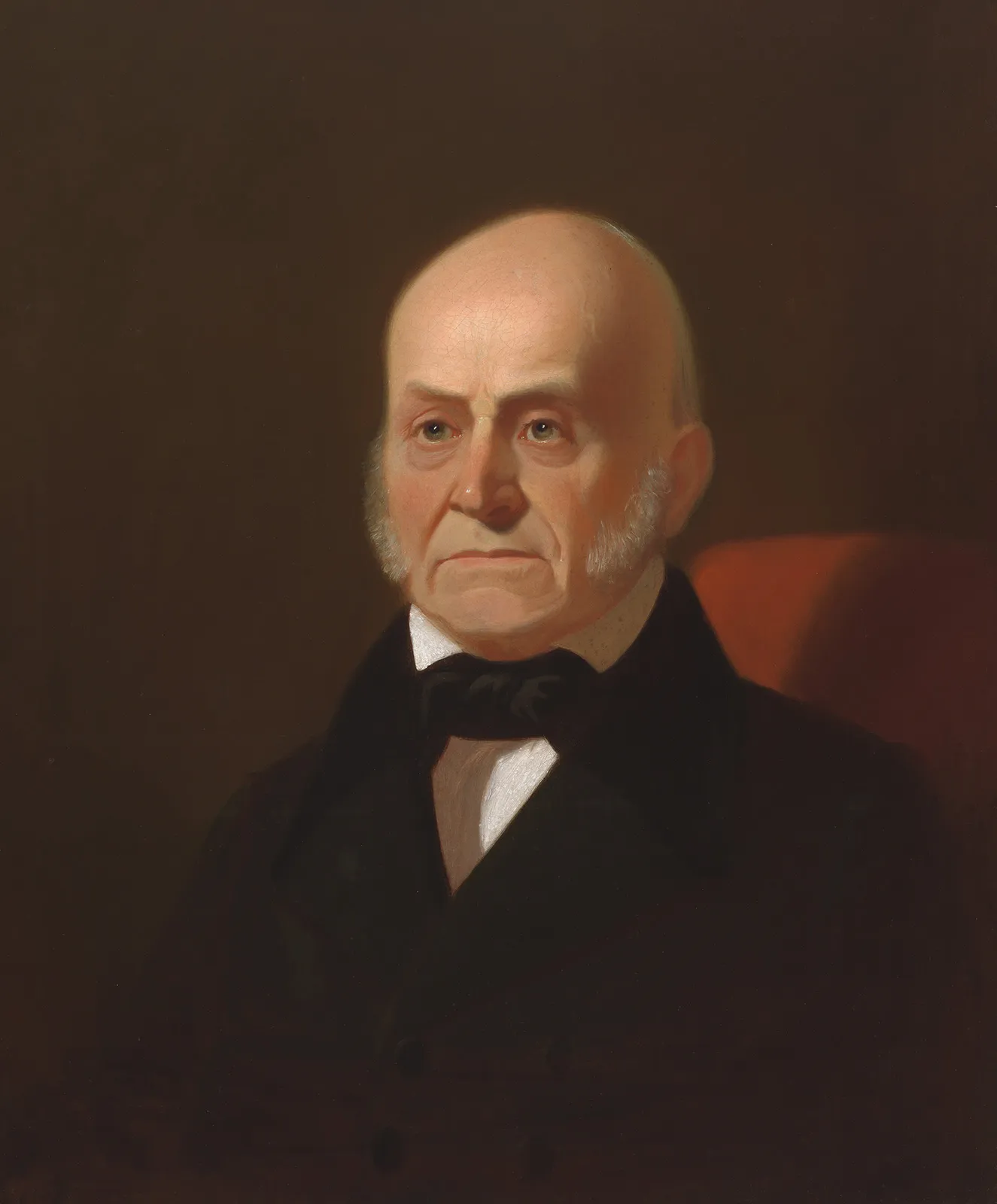

Featured Image: King George III

Much of Colonial America breathed a sigh of relief at the news that the Stamp Act of 1765 was repealed; but the more radical elements in America saw the falsehood it revealed as the Declaratory Act attached to the repeal was read. King George demanded the Declaratory Act be part of the agreement that repealed the Stamp Act. James Otis and Samuel Adams of Massachusetts, Patrick Henry of Virginia and Christopher Gadsden of South Carolina realized the dangers this act contained. It declared that the colonies were as bound by Parliaments regulations as the citizens of England. The act closely mirrored the Declaratory Act of 1719 as was applied to Ireland. (The American Colonies Act of 1766 was the official name of the Declaratory Act applied to the American Colonies as part of the repeal of the Stamp Act)

The “Mutiny Act of 1765” was another sore that the colonies found to be untenable as it allowed soldiers to be quartered in private homes. Contrary to the widely held belief, it was not the work of George Grenville, but that of officers due to the lack of barracks to house the soldiers who were posted in colonial seaports. The repeal of this act due to stiff colonial resistance did little to soothe the colonials as they believed it was a ministerial effort to relieve them of their liberty.

Colonial America declared the right to self acts of taxation; Parliament replied that the colonies were represented as they all had agents that represented the individual colonies. To this the colonies replied, yes, we have agents that represent each colony, that the agents could petition and even address Parliament individually, but they could not vote on any legislation that was to be applied to the colonies. To this argument the Parliament turned a deaf ear referring to the Declaratory Act as their right to act for the colonies. This only pushed the more vocal members of the colonial assemblies to deny Parliament the right to act for the colonies in any legislation.

To add insult to injury, the Anglican Church began to demand that they be allowed to levy and demand tithes be paid to the Church of England. This was an affront to all the diverse sects that existed in Colonial America even as the Roman Catholic Church was allowed to resurface in England. The call for an American Bishop to the Anglican Church not only angered the other religious groups in America, but brought out the denial of any church to be the recognized religion of the American colonies.

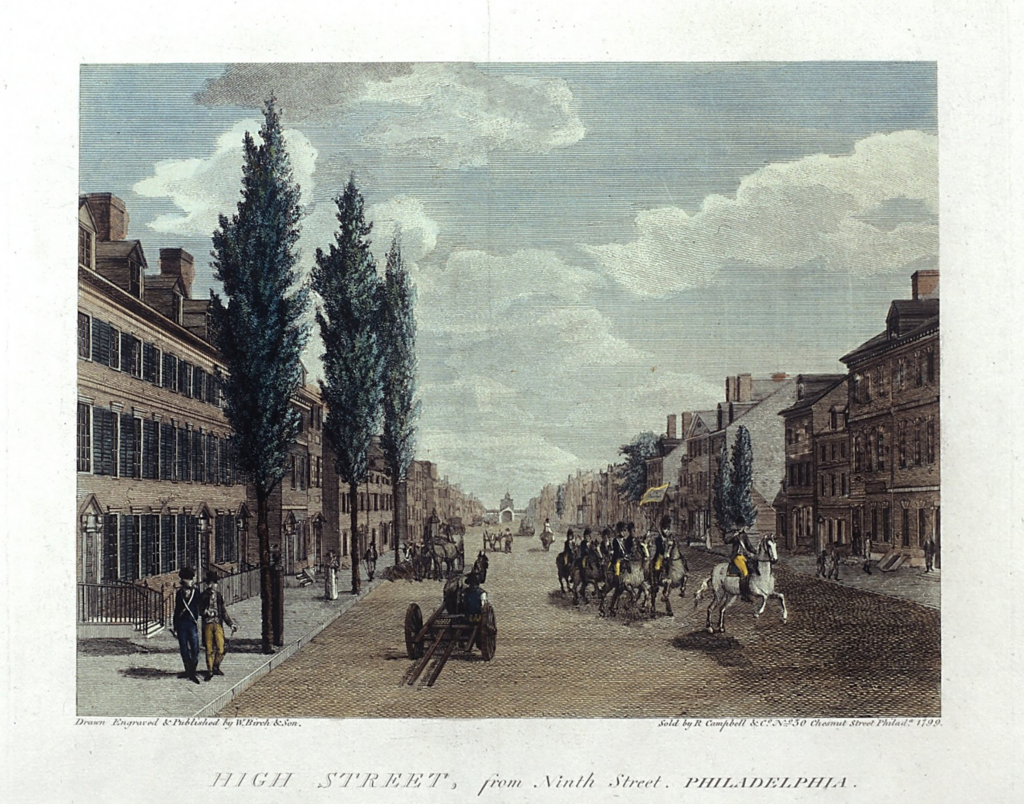

One of the more stark differences between the English citizenry and Colonial America was the lack of extreme poverty in the colonies. Travelers to the colonies saw the standard of living especially in the southern colonies often rivaled the more affluent members of English society. To the English eye this was an effort on the part of the Americans to state that they were on an equal footing with the English. The colonies were viewed as inferior workmen whose place in society was to furnish England with raw materials and referred to the colonies as “our colonies”. To this many colonials said, “It was not the sweat of the English brow that made the colonies what they are” and were offended that the claim of colonial ownership by England and by extension that the Americans were essentially “degenerate Englishmen”.

To state that the colonies did not have supporters in England would not give due recognition to many. A number of radicals in England adopted a conciliatory attitude towards the Americans, John Wilkes, John Horn Tooke, Joseph Preistly, Richard Price and Catherine Macaulay among others were sympathetic to the colonial cause. But King George the 3rd and his ministers ruled England and it was their official attitude that the colonies were to be under the rule of Parliament. They contended that the colonies had been protected from foreign incursions by way of the British Army and Navy, therefore they owed fealty to the British Crown.

General Thomas Gage’s stubborn support for the Stamp Act was reflected in his statement,” I think it would be for our own interest to keep the settlers within reach of the Sea-Coast as long as we can and to cramp their Trade as far as it can be done prudentially”. By contrast, Lord Camden (Charles Pratt, first Earl of Camden) prophetically stated, “It is impossible that this petty island can continue in dependence that mighty continent, increasing daily in numbers and in strength. To protract the time of separation to a distant day is all that can be hoped for”.

The peace that many on both sides of the Atlantic desired was not to be. The colonials were not yet ready to seek separation from England, but neither were they ready to allow Parliament the right to tax the colonies unless some kind of reconciliation could be found. A power sharing agreement had some Englishmen thinking along the lines of an Imperial Federation. This would resolve many of the disagreements that kept the two parties apart, but this too was not to be.

In an Imperial Federation, America would be on an equal footing with England. This chafed many Englishmen as they were not able to accept the idea that the colonies were anything more than British property and the Americans could not and would not accept secondary citizenship within the Empirical Federation. Hope for the Imperial Federation evaporated as the colonies imposed a boycott of English manufactured goods with the “Nonimportation Agreement of 1768”.

The impasse between England and Colonial America would continue.