Woodrow Wilson’s …

Woodrow Wilson’s Christmas Grift of 1913

George Ford Smith for Mises.org

We think of thieves as conducting their work when no one is looking, such as breaking into a house while the owners are away. But the most successful thieves have done their stealing in plain sight, on a grand scale, while the owners were home and often with their tacit approval, though with sleights of hand that few are able to detect. Such a theft occurred when Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act into law on December 23, 1913.

A central bank such as the Fed has a remarkable character. According to establishment boilerplate, its purpose is to stabilize the economy and ensure prosperity and “full employment.” The decision makers at the Fed are of necessity selected for their superhuman brilliance and neutrality of judgment, thus qualifying them to adjust the amount of money available to the banks so that they may in turn serve the interests of a public numbering some 330 million people.

If for some reason certain members of the public don’t reap the benefits of this policy—or worse, end up losing their jobs, their savings, their businesses, and their homes—it’s not because the Fed itself is a bad idea. How could it be? Without the Fed as an emergency lender, bankers threw the economy into panics in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

But there’s another side to the Fed’s character that is somewhat less wholesome than its public image and is best revealed by the way it was founded.

The Bankers’ Dream

Before the Fed’s founding, bankers in general and Wall Street in particular complained about US currency’s lack of “elasticity.” “Elasticity” in this context is one of the great euphemisms of human history. According to lore, this missing feature of “hard” money, such as gold or silver, was responsible for the panics of 1873, 1884, 1893, and 1907. The supply of the coins that were behind the paper banknotes couldn’t be increased when needed. Gold and silver were therefore said to be inelastic. Because of this inelasticity, the legend persisted that banks were having trouble meeting the demand for farm loans at harvest time, as G. Edward Griffin explains in The Creature from Jekyll Island:

To supply those funds, the country banks had to draw down their cash reserves which generally were deposited with the larger city banks. This thinned out the reserves held in the cities, and the whole system became more vulnerable. Actually, that part of the legend is true, but apparently no one is expected to ask questions about the rest of the story.

Several of them come to mind. Why wasn’t there a panic every Autumn instead of just every eleven years or so? Why didn’t all banks—country or city—maintain adequate reserves to cover their depositor demands? And why didn’t they do this in all seasons of the year? Why would merely saying no to some loan applicants cause hundreds of banks to fail?

The Morgan and Rockefeller bankers on Wall Street dreamed of having a central bank that could supply money when needed, as a “lender of last resort.” A central bank would also control the banks’ inflation rate. If bank reserves could be maintained at a central bank and a common reserve ratio established, then no single bank could expand credit more than its rivals, and therefore there would be no bankruptcies caused by currency’s draining from overly inflationary banks. All banks would inflate in harmony, and there would be tranquility and profits for all.

The bankers who traveled a thousand miles to meet on Jekyll Island in November 1910 understood they needed a cartel to bring their dream to life. And they needed the threat of state violence for the cartel to work.

Thus, included in their secret meeting were two politicians serving as the bankers’ advocates in Washington. The bankers planned to establish their cartel over the Christmas holidays, while the American public was distracted, though for political reasons it was delayed until 1913.

The public would be a hard sell. Americans were profoundly suspicious of Wall Street and cartels. They distrusted anything big in business or government. A central bank operating for the benefit of the big banks had no chance of becoming law, unless it was promoted as shackling Wall Street itself. This could be accomplished, it was widely believed, through a government bureaucracy of overseers.

The Pujo Committee

Frequent speeches by Wisconsin senator Robert LaFollette and Minnesota congressman Charles Lindbergh brought public outrage over the “money trust” to a boil. LaFollette charged that the entire country was under the control of just fifty men; Morgan partner George Baker disputed the allegation, claiming it was no more than eight men. Lindbergh pointed out that bankers had controlled all financial legislation since the Civil War through committee memberships.

Government, acting as the sword of justice, decided to act, with most people oblivious to the fact that the executioner and the accused were one and the same. In response to the accusations, it formed a new subcommittee, which held hearings from May 1912 until January 1913.

The Pujo Committee was headed by Louisiana congressman Arsène Pujo, then roundly considered to be a spokesman for the “oil trust.” The hearings followed the usual pattern, bringing forth immense quantities of statistics and testimonies from bankers themselves. Though the hearings were conducted largely because of the charges brought forth by LaFollette and Lindbergh, neither man was allowed to testify.

Under the direction of Paul Warburg, the principal author of the Jekyll Island plan that in its essentials became the Federal Reserve Act, the banks provided 100 percent financing for something called the National Citizens League, the purpose of which was to create the illusion of grassroots support for Warburg’s brainchild.

University of Chicago economics professor J. Laurence Laughlin was put in charge of the league’s propaganda, ostensibly to bring a measure of objectivity to the discussions. John D. Rockefeller, whose representatives at Jekyll were Senator Nelson Aldrich and bank president Frank Vanderlip, had endowed the university with $50 million.

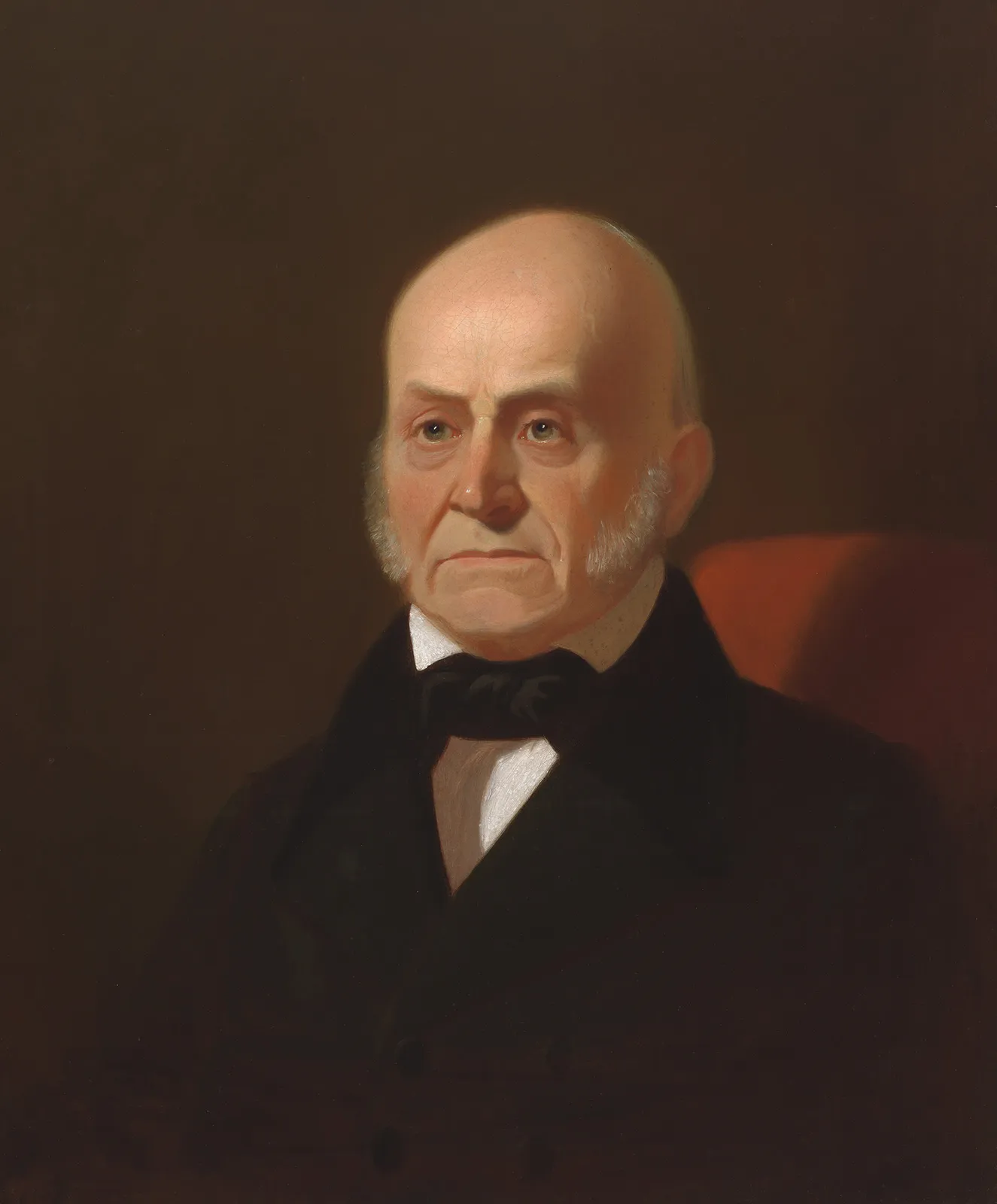

Woodrow Wilson was an outspoken critic of the money trust in his 1912 presidential campaign, all the while receiving funding from the very trust he was condemning. Wilson said:

I have seen men squeezed by [the money trust]; I have seen men who, as they themselves expressed it, were put “out of business by Wall Street,” because Wall Street found them inconvenient and didn’t want their competition.

Benjamin Strong Runs the Show

When the Fed began operations in late 1914, the man in charge of the system was Morgan banker Benjamin Strong Jr., one of the Jekyll Island attendees. Strong served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from its inception until his death on October 16, 1928. Strong, in the Morgan tradition, was an anglophile who inflated the US money supply from 1925–28 to keep Britain from losing gold to the US. Details of Strong’s reign and the precrash conditions he created can be found in Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression:

The long-run tendency of the free market economy, unhampered by monetary expansion, is a gently falling price level, falling as the productivity and output of goods and services continually increase. The Austrian policy of refraining always from monetary inflation would allow this tendency of the free market its head and thereby remove the disruptions of the business cycle.

The Chicago goal of a constant price level, which can be achieved only by a continual expansion of money and credit, would, as in [Benjamin Strong’s policy of the] 1920s, unwittingly generate the cycle of boom and bust that has proved so destructive for the past two centuries.