Pronghorn (Antiocapra Americana)

Although not a true antelope, it is a mammal native to the western US commonly called the Pronghorn Antelope. Its closest living relatives are the giraffe and okapi; animals that are native to Africa. The pronghorn is the fastest of all land mammals in the Western Hemisphere.

The pronghorn was a food animal for the American Indian, it was first described by Spanish explorers. Being an animal of great speed (up to 55 mph) and endurance, the native Indians hunted them on horseback or by driving them into a surround and then dispatching the animals.

The Corps of Discovery were the first to scientifically describe and study the pronghorn. They described the animals as being rather small (4 feet 6 inches from nose to tail; approximately 5 feet in height and weighing on average110 lbs, the female weighing slightly less, about 100 lbs). With large eyes and a 320 degree field of vision they can be very hard to stalk, making them a trophy that the hunter definitely earns.

Pronghorns have glands on each hoof; the glands have antimicrobial properties that give them protection against soil and mammalian pathogens. The hooves have two long pointed toes that help cushion shock when running at high speeds. Male scent glands, which are located on the side of its head and used to scent mark its territory, are highly odiferous and when alarmed secrete an oily substance that is reminiscent of buttered popcorn. Hair on the rump flairs sending a visual signal as well as scent to alert others to danger.

Pronghorns tend to prefer open areas with long vistas at elevations between 3,000 to 6,000 feet. They also prefer to range within 5 miles of a reliable water source. Migration routes may be as long as 160 miles due to range conditions and weather.

Bighorn Sheep ( Ovis Canadensis)

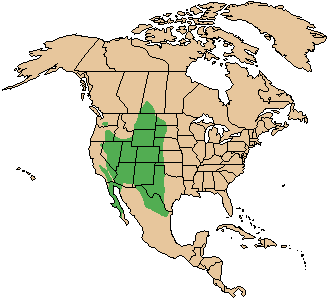

The Bighorn is a species of native North American sheep named for its large horns. They originally migrated to North America from Siberia by way of the Bering Land Bridge during the Pleistocene Era approximately 750,000 years ago. They diverged from the Siberian sheep some 600,000 years ago as they spread through the western US to northern Mexico. The main differences today are the larger mountain bighorn and the smaller desert bighorn; the two subspecies came into being during the Illinoian glaciation (300,000 to 90,000 years ago).

Both males and females have horns with the male having the larger horns and females with shorter horns with less curvature. Coloration ranges from light brown to dark chocolate with a white rump and lining the back side of all four legs. Males may weigh as much as 300 lbs while females usually weigh in at just under 200 lbs. Males typically are about 38 inches at the shoulder and 68 inches from nose to tail. Females measure approximately 33 inches tall and 59 inches long. Internal adaptations in the males serve to cushion the brain against damages during the rut; these clashes may be heard over long distances.

Ewes have a 6 month gestation period, the rut usually occurs in November and the lambs are born in May. Lambs born early are more apt to survive as the ewes move to less accessible areas to avoid predation leaving lambs born later to less milk from the ewe. Lambs usually weigh in at 9 lbs and can walk within hours of being born.

The Corps of Discovery made numerous notations about the Big Horn, naming rivers and other lesser streams for this iconic animal. Not all of these names remained as the country was settled.

Bristlecone Pine (Pinaceae Pinus)

The bristlecone is a long lived species usually found at high altitudes with harsh winters and poor soils. They get their name from the vicious prickly spines that are common among the species known as bristlecone pines. Among the longest-lived life forms on planet earth, they do not do well in areas of heat, high humidity and rich soils.

Even with low reproduction rates, they may be the first pines to occur in new open ground as many species of trees cannot survive the harsh winters and poor soils of higher elevations. These species of pines tend to do quite well in rocky dolomite soils with sparse precipitation but are susceptible to root rot in humid soils, making them a poor choice for gardens and as ornamentals.

The Bristlecone Pines are three distinct species: The Foxtail Pine (Pinus Balfouriana) is found in the Klamath Mountains of southern Oregon and northern California. The Rocky Mountain bristlecone pine (Pinus Aristata) is scattered over parts of Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico. The Great Basin bristlecone pine (Pinus Longaeva) is found in California, Nevada and Utah.

These hardy pines grow at just below tree line between 5,600 and 11,200 feet in shallow soils, usually dolomite but also limestone, sandstone and quartzite soils. Soils that often are alkaline, high in calcium and magnesium and low in phosphorus’ precluding many other plant varieties but allows the bristlecone species to thrive. Cold temperatures, dry soils, high winds and short growing seasons make these hardy plants grow very slowly thus adding to their hardy dispositions and long lives.

Dense, resinous wood makes them resistant to insect infestations, fungi and other pests add to the longevity of this iconic trio of high altitude pines.

The Channeled Scab Lands of Eastern Washington

This geologic feature is a predominately barren, soil free area of coulees, dry flood channels and flat-lying lava flows that remained after numerous cataclysmic floods over the last two million years, covering an area of between 1,500 and 2,000 square miles of eastern Washington state.

These floods were the result of periodic breaks in the glacial ice dam that backed up a huge lake (prehistoric Lake Missoula) into what is now western Montana. Numerous times this tableau was repeated with the last of these floods occurring between 18,200 and 14,000 years ago at the end of the Pleistocene epoch.

The Cordilleran Ice Sheet was responsible for the huge lake that formed behind the Purcell Trench Lobe, a finger of mountainous terrain that allowed the ice sheet to confine the waters that became Lake Missoula. It was the breaking of this dam that allowed the flood waters to charge across the relatively flat terrain of eastern Washington and create these scab lands.

The scientific furor these floods raised raged over a 40 year period as J. Harlen Bretz formulated his theory to explain these scab lands. In 1925 J. T. Pardee suggested to Bretz that the draining of what was known as Lake Missoula on numerous occasions may have been what caused the floods necessary to create these soil deficient areas of buttes and basins.

It wasn’t until 1970 that much of these two men’s research was finally accepted and not until 1979 the Bretz was posthumously awarded the Penrose Medal to recognize that his theories were totally accepted as scientific fact.

You can find the first three parts of this series here, here, and here