What Is the Shroud of Turin and Why Is It Controversial?

What Is the Shroud of Turin and Why Is It Controversial?

The centuries-old cloth has a long history of stoking both faith and skepticism.

The Shroud of Turin, currently housed in the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist, was first shown publicly in the 14th century. Philippe Lissac/Getty Images

This story was originally published on The Conversation. It appears here under a Creative Commons license. atlasobscura.com

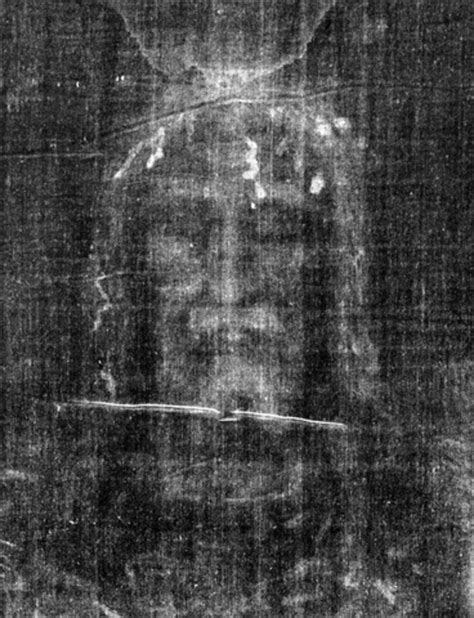

The Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in Turin, Italy, houses a fascinating artifact: a massive cloth shroud that bears the shadowy image of a man who appears to have been crucified. Millions of Christians around the world believe that this shroud—commonly called the Shroud of Turin—is the cloth that was used to bury Jesus after his crucifixion and that the image on the shroud was produced miraculously when he was resurrected.

The evidence, however, tells a different story.

Scientists have questioned the validity of the claims about the shroud being a first-century object. Evidence from carbon-14 dating points to the shroud being a creation from the Middle Ages. Skeptics, however, dismissthese tests as flawed. The shroud remains an object of faith, intrigue, and controversy that reappears periodically in the public sphere, as it has in recent weeks.

As a scholar of early Christianity, I have long been interested in why people are motivated to create objects like the shroud and also why people are drawn to revere them as authentic.

The first public appearance of the shroud was in 1354, when it was displayed publicly in Lirey, a small commune in central France. Christian pilgrims traveled from all over to gaze upon the image of the crucified Jesus.

Pilgrimages like this were common during the Middle Ages, when relics of holy people began to appear throughout Europe. The relic trade was big business at the time; relics were bought and sold, and pilgrims often paid a fee to visit them. Many believed that these relics were genuine. In addition to the shroud, pilgrims visited Jesus’ crib, splinters from the cross, and Jesus’s foreskin, just to name a few.

But even in the 14th century, when the relic trade in Europe was flourishing, some were suspicious.

Even in the 14th century, some were suspicious.

In 1390, only a few decades after the shroud was displayed in Lirey, a French bishop named Pierre d’Arcis claimed in a letter to Pope Clement VII not only that the shroud was a fake but that the artist responsible for its creation had already confessed to creating it. Clement VII agreed with the assessment of the shroud, although he permitted its continued display as a piece of religious art.

The shroud has been the subject of much scientific investigation in the past several decades. Data from scientific tests matches what scholars know about the shroud from historical records.

In 1988, a team of scientists used carbon-14 dating to determine when the fabric of the shroud was manufactured. The tests were performed at three labs, all working independently. Based on data from these labs, scientists said there was “conclusive evidence” that the shroud originated between the years 1260 and 1390.

Results from another scientific study over 30 years later appeared to debunk these findings. Using an advanced X-ray technique to study the structure of materials, the scientists concluded that the fabric of the shroud was much older and could likely be from the first century. They also noted, however, that their results could be considered conclusiveonly if the shroud had been stored at a relatively constant temperature and humidity—between 68-72.5 degrees Fahrenheit and 55 percent to 75 percent—for the entirety of two millennia.

This would be highly unlikely for any artifact from that period. And when it comes to the shroud, the conditions under which it has survived have been less than ideal. In 1532, while the shroud was being kept in Chambéry in southern France, the building it was housed in caught fire. The silver case that held the shroud melted; despite intricate repair attempts, the burn marks in the fabric remain visible to this day. It was saved from another fire in Turin as recently as 1997.

Despite the ongoing debate, the carbon-14 dating results have continued to provide the most compelling scientific evidence that the shroud is a product of the Middle Ages and not an ancient relic.

The shroud is undeniably a masterful work of art, crafted with remarkable skill and using methods that were complicated and ahead of their time. For centuries, many experts struggled to understand how the image was imprinted onto the fabric, and it wasn’t until 2009 that scientists were successfully able to reproduce the technique using medieval methods and materials.

Pope Francis once referred to the shroud as an “icon,” a type of religious art that can be used for a variety of purposes, including teaching, theological expression, and even worship. Without addressing the authenticity of the shroud, the pope suggested that by prompting reflection on the face and body of the crucified Jesus, the shroud encouraged people to also consider those around them who may be suffering.

It is at least possible that the shroud was created as a tool that would encourage viewers to meditate on the death of Jesus in a tangible way.

Ultimately, the shroud of Turin will continue to intrigue and draw both believers and skeptics into a debate that has spanned centuries. But I believe that the shroud encourages viewers to think about how history, art, and belief come together and influence how we see the past.

Eric Vanden Eykel is an associate professor of religious studies at Ferrum College in Virginia.